IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs April 2017, IASbaba's Daily News Analysis, National, UPSC

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 1st April 2017

Archives

ECONOMY

TOPIC: General Studies 3

- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment

- Inclusive growth and issues arising from it

GST – Continuation

Introduction

GST is a very important tax reform. It is initiated to achieve a one nation one tax regime which will benefit both corporate sector and the consumers. The government revenues are supposed to increase and thus integrate India into the global league of nations.

Issue:

The Lok Sabha has duly given its assent to necessary Central legislation to operationalise the Goods and Services Tax, nearly 17 years after the government began discussions on the prospects for a unified indirect tax regime across the country.

- It is eyeing a July 1 rollout for the GST, which will replace the multiple Central and State-level taxes and levies that make doing business in India a compliance nightmare today.

- The long and winding road for this reform, marked by political about-turns, has had a fairly straight trajectory in recent months, following the constitutional amendments last August.

- The GST Council has managed to thrash out a consensus on several issues relating to the administration and the legislative provisions for the new tax system within six months.

- The fact that apparently intractable positions held by the States as well as the Centre on the sharing of administrative powers, for instance, have been reconciled without the Council resorting to a majority vote inspires confidence.

- So does the alacrity with which the Centre has moved to secure Parliament’s nod for four enabling pieces of legislation within a fortnight of the Council’s approval.

- State Assemblies should do the same to pass the State GST law by holding special sessions if need be.

GST and Indian Economy:

For Indian businesses that have been seeking the reform, it is now time to come to terms with the fine print and embrace the tax system.

- The GST Council, meeting again on Friday to clear four pending sets of regulations, must sign off on which of the five GST rates will apply to different products and services.

- Clarity on the applicable rates will help industry alter their accounting systems, supply chains and pricing strategies.

- But some provisions in the GST laws have the industry in a tizzy.

- While the highest GST rate has been pegged at 28%, the integrated GST law has set a ceiling of 40%.

- Though an enabling provision, it gives the government too much leeway to alter the rate structure in coming years without seeking Parliament’s nod.

- Compare this to the cess ceiling of 15% on luxury cars, for instance, which are likely to see a 12% cess to start with.

- On several other fronts, the final laws haven’t changed much from their draft versions, despite industry red-flagging several provisions.

- These include the anti-profiteering clauses to curb ‘unjust enrichment’ of firms, the requirement for branch offices to register separately in each State, and treating all transactions between related parties (including head office and branch offices) as taxable.

- For the services sector, in particular, compliance requirements could go up multi-fold.

- It is still not too late for the GST Council to offer some exemptions or resist operationalising some of these provisions through the subordinate rules and regulations in order to address genuine industry grievances.

Conclusion:

Taxation is an important power of the government which has to be used in a balanced and inclusive manner. Indirect tax which is regressive in comparison to direct taxes should be rationalized so that they don’t burden either side keeping government revenues high. GST is a major reform in this direction and should be implemented after due diligence and all stakeholders consensus.

Connecting the dots:

- GST will be a revolutionary taxation reform for India. Elaborate on the challenges on federal and fiscal front w.r.t change centre state relations.

NATIONAL

TOPIC:

General Studies 2

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

General Studies 3

- Infrastructure: Airports

Connecting the cities: UDAN

What is it?

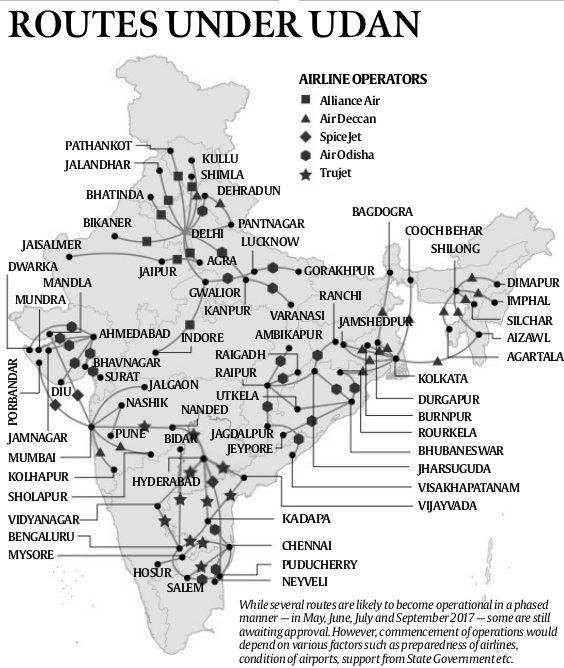

- Regional Connectivity Scheme, or UDAN (Ude Desh Ka Aam Naagrik), was introduced as part of the National Civil Aviation Policy 2016.

- It provides an opportunity to take flying to the masses by way of fiscal incentives, infrastructure support and monetary subsidies (viability gap funding).

- The scheme, which will run for 10 years, will work to revive existing airstrips and airports.

- As per FICCI, about 44 airports across the country, from 414 underserved and unserved airports, have ‘high potential’ for operations under the Regional Connectivity Scheme (RCS) for civil aviation, UDAN. They have been selected based on geographical, operational and commercial parameters.

- So far, 22 States have joined the RCS and 30 airports have been identified where operations could be started immediately.

Funding the scheme

- Airfares will be capped at Rs 2,500 for an hour’s journey on a flight operating to and from a regional airport.

- The government will provide subsidies to regional airlines to offer half the seats on a discounted rate. However, the subsidies will mainly be provided by taxing the air passengers on other domestic routes in the form of a ‘small’ levy.

- The subsidy to airlines will be provided through a reverse bidding process, which means if there is a demand from multiple airlines to fly on regional routes the ones asking for the least financial support will get the subsidy.

- In routes where a proposal comes from only one airline, the government will give the subsidy based on normative pricing, meaning it will calculate the subsidy amount based on various parameters.

Picture credit: http://images.indianexpress.com/2017/03/udan.jpg

Opportunities

- India has highly untapped civil aviation opportunities. In the first round of bids, 11 new or existing airline operators pitched for more than 200 routes. The Centre has approved 27 proposals from five players, adding 128 routes to India’s aviation map. The estimate is that this will add 6.5 lakh new seats with a subsidy of Rs.200 crore.

- Of these, six proposals for 11 routes don’t seek any subsidy under the scheme, proving there is an untapped economic potential. The benefits for tourist hotspots such as Agra, Shimla, Diu, Pathankot, Mysuru and Jaisalmer would now be just a short flight away, replacing cumbersome road or rail journeys.

- The multiplier effects of aviation activity, including new investments and employment creation for the local economies of other destinations could be equally profound.

- If this model is sustainable and more regional flights come up under the scheme, it will support the capacity-constrained airports such as Mumbai. The second airport at Navi Mumbai may help ease congestion. However, it is still years away and so initiation to develop such airports has to begin soon.

- In cities where new airports have been developed, such as Bengaluru, abandoned old facilities could be revived as dedicated terminals for low-cost and regional flights.

- Separately, new no-frills airports must be encouraged where traffic is expected to hit saturation point in coming years.

- It is time to revisit provisions that offer existing private operators of large airports (burdened by debt) the right of first refusal on any new airport proposed within 150 km.

- The regional civil aviation development must start a rethink within the Indian Railways, as it could now ease traffic on some routes. Even if there is less of passenger traffic, the cargo traffic will keep the airports alive.

Challenges

- There still needs to be creation of enabling conditions for RCS to be successful. One of it includes right size of aircrafts. Many of the airports (identified for RCS) do not have big runways, so they can’t take regular aircraft. Thus there need to be smaller aircraft for short runways for short takeoffs and landings. However, such kind of aircrafts are not present in India.

- Such aircraft needs specialised crew. There is shortage of pilots and crew which demands urgent attention. Training to the aviation personnel takes time. For training, there requires adequate infrastructure, trained manpower and sufficient funds to turn out pilots and crew.

- Viability Gap Funding under the RCS need to be extended from the proposed three to five years or more as these airfields might taken even longer to become financially sustainable.

- There are fears that a flight from an UDAN location will be low priority for air traffic controllers in big cities. This may not be favourable for air carriers as well as passengers.

Conclusion

Five airlines – Alliance Air, Air Odisha, TruJet, Spicejet, Air Deccan – will be a part of the regional connectivity model which is based on ‘viability gap funding’. Under this, 80% of the cost will be borne by the state government and the rest by the centre. The Centre as of now has allotted Rs 205 crore to start of the process. Bringing Tier 2 and Tier 3 into the country’s aviation network is a significant development in a country where 80% of air travel is between the metros. Though the business model is not lucrative, it is expected to be viable. The scheme will foster regional connectivity, make businesses and trade more efficient, enable medical services and promote tourism.

Connecting the dots:

- How is regional civil aviation connectivity expected to affect India’s connectivity issues? Analyse.

MUST READ

The mob’s bias

Transcending democracy beyond elections

Sharpening a pro-choice debate

A different kind of change

Farmers need better prices

Rate, and don’t rank, academic institutions