The Big Picture- RSTV

Ban of Single Use of Plastic and Waste Management

Archives

TOPIC: General Studies 3

- Conservation, environmental pollution and degradation

In 5 minutes, around the time it takes to read this piece, around 5 million plastic bottles will be bought around the world, many of those in India.

According to a UNEP report, more than 60 countries have some form of regulation — ban or taxes — on production and use of plastic. But enforcement has not been robust, and only about 30 per cent of the countries reported a drop in consumption. India’s own record in implementing plastic bans has been poor. But by raising the pitch on plastic use, the government is hoping to make more manufacturers comply to regulations.

If not recycled, plastic can take a thousand years to decompose, according to UN Environment, the United Nations Environment Programme. At landfills, it disintegrates into small fragments and leaches carcinogenic metals into groundwater. Plastic is highly inflammable — a reason why landfills are frequently ablaze, releasing toxic gases into the environment. It floats on the sea surface and ends up clogging airways of marine animals.

In June 2018, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India would eliminate single-use plastics by 2022.

- India generated 26,000 tonnes per day (TPD) of plastic waste in 2017-18, the latest year for which data is available, according to the Central Pollution Control Board. Of that, 15,600 TPD, or 60 per cent , was recycled. The rest ended up as litter on roads, in landfills or in streams. Uncollected plastic waste poses a huge threat to species on land and in water.

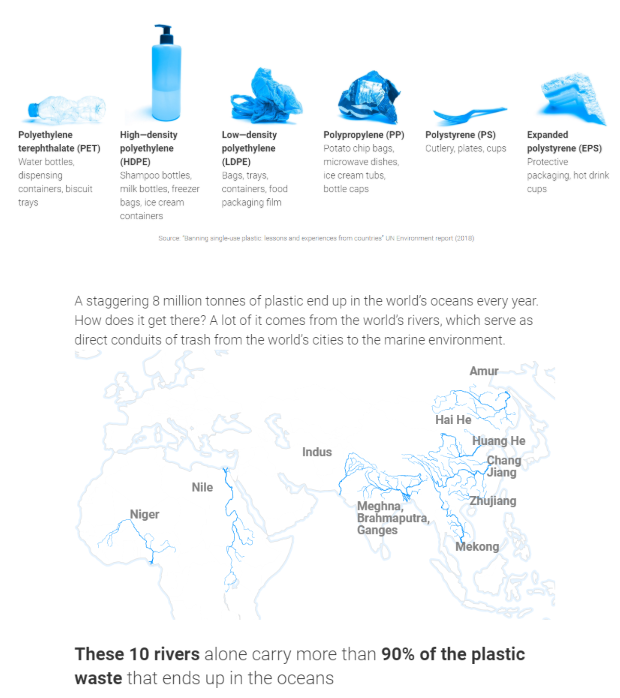

- Around eight million tonnes of plastic waste enter the ocean every year. The river Ganga alone took 1.15 lakh tonnes of plastic into the ocean in 2015, second only to China’s Yangtze, according to a research paper published in Nature Communications magazine.

- India’s plastic recycling rate is 60 per cent , three times higher than the global average of 20 per cent , and India’s per capita plastic consumption — at 11 kg in 2014-15 — is less than half the global average of 28 kg. In 2016, India said it wanted to increase the per capita plastic use to 20 kg by 2022.

The Issue: Since half the plastic now produced is meant to be used only once, India has to figure out what plastic it wants to use and ban — and how it will recycle all that trash.

India lacks an organised system for management of plastic waste, leading to widespread littering across its towns and cities.

- The ban on the first six items of single-use plastics will clip 5% to 10% from India’s annual consumption of about 14 million tonnes of plastic, the first official said.

- Penalties for violations of the ban will probably take effect after an initial six-month period to allow people time to adopt alternatives, officials said.

- Some Indian states have already outlawed polythene bags.

- The federal government also plans tougher environmental standards for plastic products and will insist on the use of recyclable plastic only, the first source said.

- It will also ask e-commerce companies to cut back on plastic packaging that makes up nearly 40% of India’s annual plastic consumption, officials say.

Use & Reuse

A key step in that direction was Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) under the Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016, which were amended last year. As part of EPR, producers, importers and brand owners — like fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) and pharma companies — are supposed to take back the plastic waste generated by their products, with the help of waste-management companies

Companies are trying to shift to single-polymer packaging, which would make it recyclable.

The Challenge: While India is one of 63 countries with EPR, its guidelines for the same continue to be vague. There isn’t much clarity on how much of single-use plastic a company puts out needs to be taken back by it.

- There is no mechanism to implement EPR. Even if the government chooses to ban certain plastics, there is a big question mark on how effective it will be. Plastic is cheap and convenient, and as long as there is demand for it, people are going to manufacture it.

- Unlike urban local bodies, gram panchayats may not have the resources to do routine checks on plastic use. Maharashtra is among the 23 states that have fully or partially banned plastic bags, but that has not stopped people from using them.

- The cigarette butt is the most commonly found litter on beaches and in rivers and lakes. A global coastal clean-up drive in 2018 found 5.7 million of them.

Plastic waste management

The Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016 notified by the Centre called for a ban on “non-recyclable and multi-layered” packaging by March 2018, and a ban on carry bags of thickness less than 50 microns (which is about the thickness of a strand of human hair). The Rules were amended in 2018, with changes that activists say favoured the plastic industry and allowed manufacturers an escape route. The 2016 Rules did not mention SUPs.

Single-use plastic alternatives

There is no viable alternative as of now for single-use plastic items. The alternative to single-use plastic items, especially single-use plastic bottles, which are used to sell packaged drinking water, needs to be affordable for the consumers. A drinking water bottle, which costs Rs 20 currently, cannot be priced higher than that. Further, customers have shown confidence in the sealed water bottles over the years and hence, the alternative should also be up to the mark.

Since recycling of plastic is not a permanent solution, manufacturers of single-use plastic have been asked to look for other alternatives that are biodegradable. Railway ministry, which manufactures and sells packaged drinking water ‘Rail Neer’ is also looking for alternatives including polymers to make their packaging biodegradable.

Are alternatives such as compostable or biodegradable plastics viable?

Although compostable, biodegradable or even edible plastics made from various materials such as bagasse (the residue after extracting juice from sugarcane), corn starch, and grain flour are promoted as alternatives, these currently have limitations of scale and cost.

Some biodegradable packaging materials require specific microorganisms to be broken down, while compostable cups and plates made of polylactic acid, a popular resource derived from biomass such as corn starch, require industrial composters. On the other hand, articles made through a different process involving potato and corn starch have done better in normal conditions, going by the experience in Britain. Seaweed is also emerging as a choice to make edible containers.

In India, though, in the absence of robust testing and certification to verify claims made by producers, spurious biodegradable and compostable plastics are entering the marketplace. In January this year, the CPCB said that 12 companies were marketing carry bags and products marked ‘compostable’ without any certification, and asked the respective State Pollution Control Boards to take action on these units.

A ban on single-use plastic items would have to therefore lay down a comprehensive mAechanism to certify the materials marketed as alternatives, and the specific process required to biodegrade or compost them. A movement against plastic waste would have to prioritise the reduction of single-use plastic such as multi-layer packaging, bread bags, food wrap, and protective packaging. Consumers often have no choice in the matter. Other parts of the campaign must focus on tested biodegradable and compostable alternatives for plates, cutlery and cups, rigorous segregation of waste and scaled up recycling. City municipal authorities play a key role here.

The Way Ahead – How to get rid of the plastic menace?

- Leading a grassroots movement to support the adoption of a global framework to regulate plastic pollution.

- Educating, mobilising and activating citizens across the globe to demand that governments and corporations control and clean up plastic pollution.

- Educating people worldwide to take personal responsibility for plastic pollution by choosing to reject, reduce, reuse and recycle plastics.

- Promoting local government regulatory and other efforts to tackle plastic pollution.

- Education and responsibility are only one side of the coin, however; the other side is infrastructure. The technology to create a circular economy by means of recycling does in fact exist, but the infrastructure needed to fully implement it is seriously lacking. Of all the plastic waste produced in the world, less than 10% is recovered due in large part to the lack of infrastructure both at home and abroad.

Must Read: Link 1 + Dangers of Plastic + Are We Drinking Plastic?

Connecting the Dots:

- What are the sustainable strategies to address the problem of plastic including e-waste? Discuss.