ECONOMY/ SOCIETY

Topic:

- GS-3: Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization, of resources, growth, development and employment.

India’s GDP fall

Context: India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracted by 7.3% in 2020-21. Between the early 1990s until the pandemic hit the country, India grew at an average of around 7% every year.

There are two ways to view this contraction in GDP.

- One is to look at this as an outlier — after all, India, like most other countries, is facing a once-in-a-century pandemic.

- The other way would be to look at this contraction in the context of what has been happening to the Indian economy over the last decade — and more precisely over the last seven years

Perhaps the best way to arrive at such a conclusion is to look at the so-called fundamentals of the economy.

| Gross Domestic Product |

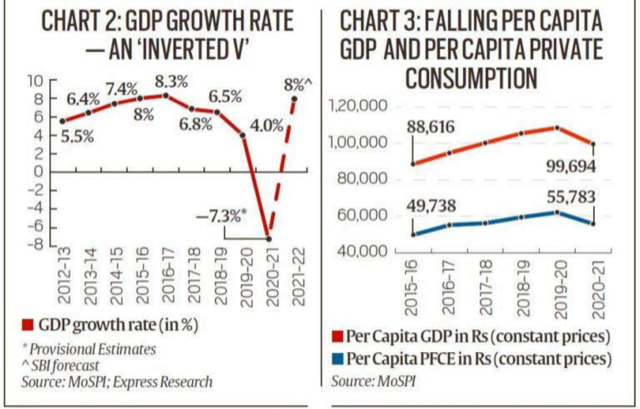

- After the decline in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, the Indian economy started its recovery in March 2013

- This recovery turned into a secular deceleration of growth since the third quarter (October to December) of 2016-17.

- The GDP growth rate steadily fell from over 8% in FY17 to about 4% in FY20, just before Covid-19 hit the country.

- Demonetisation on November 8, 2016 is seen by many experts as the trigger that set India’s growth into a downward spiral.

- India’s GDP growth pattern resembled an “inverted V” even before Covid-19 hit the economy.

|

| GDP per capita (GDP divided by the total population) |

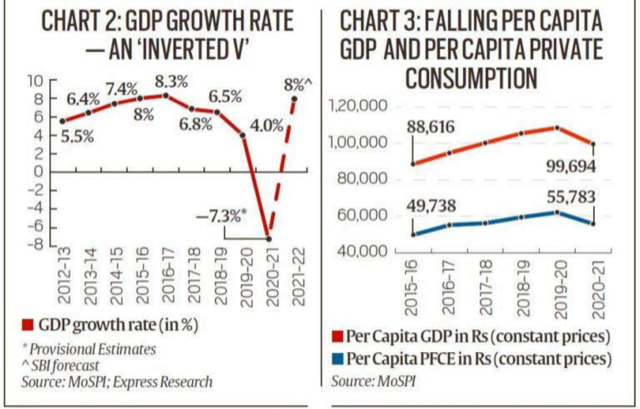

- As the red curve in Chart 3 (above) shows, at a level of Rs 99,700, India’s GDP per capita is now what it used to be in 2016-17 — the year when the slide started.

- As a result, India has been losing out to other countries. A case in point is how even Bangladesh has overtaken India in per-capita-GDP terms

|

| Unemployment rate |

- This is the metric on which India has possibly performed the worst.

- Unemployment was at a 45-year high in 2017-18 — the year after demonetisation and the one that saw the introduction of GST.

- Then in 2019 came the news that between 2012 and 2018, the total number of employed people fell by 9 million — the first such instance of total employment declining in independent India’s history.

- As against the norm of an unemployment rate of 2%-3%, India started routinely witnessing unemployment rates close to 6%-7% in the years leading up to Covid-19. The pandemic, of course, made matters considerably worse.

|

| Inflation rate |

- After staying close to the $110-a-barrel mark throughout 2011 to 2014, oil prices (India basket) fell rapidly to just $85 in 2015 and further to below (or around) $50 in 2017 and 2018. This fall allowed government to tame the high retail inflation in the country.

- But since the last quarter of 2019, India has been facing persistently high retail inflation. Even the demand destruction due to lockdowns induced by Covid-19 in 2020 could not extinguish the inflationary surge

- Going forward, inflation is a big worry for India.

|

| Fiscal deficit |

- On paper, India’s fiscal deficit levels were just a tad more than the norms set, but, in reality, even before Covid-19

- In the Union Budget for the current financial year, the government conceded that it had been underreporting the fiscal deficit by almost 2% of India’s GDP.

|

| Rupee vs dollar |

- A US dollar was worth Rs 59 in 2014. Seven years later, it is closer to Rs 73.

- The relative weakness of the rupee reflects the reduced purchasing power of the Indian currency.

|

What’s the outlook on growth?

- The biggest engine for growth in India is the expenditure by common people in their private capacity. This “demand” for goods accounts for 55% of all GDP.

- In Chart 3, the blue curve shows the per capita level of this private consumption expenditure, which has fallen to levels last seen in 2016-17. This means if the government does not help, India’s GDP may not revert to the pre-Covid trajectory for several years to come.

- It is for this reason that the latest GDP should not be viewed as an exception

Connecting the dots: