IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Aug 2016, National, UPSC

Archives

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 6th August, 2016

NATIONAL

TOPIC:

General Studies 1

- Poverty and developmental issues

General Studies 2

- Issues relating to development and management of Social Sector/Services relating to Health, Education, Human Resources

- Issues relating to poverty and hunger

The lost tribe of Odisha

Malnutrition kills

- Nineteen Juang tribal children have died in the last three months, May-July 2016

- Reason: Acute malnutrition-related diseases

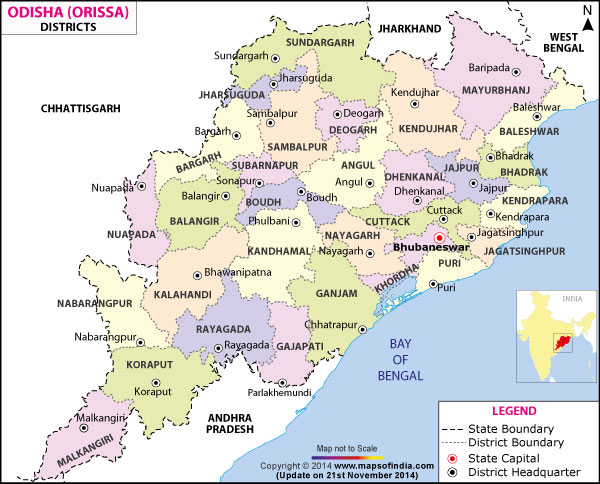

- Where: inaccessible hamlets atop the Nagada hills, Jajpur district, Odisha

- Current update: State government has finally taken its notice and started taking action

Photo credit: http://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/orissa/orissa-district-map.jpg

Nagada hills- A history of neglect

- Odisha has 62 tribes, the highest number among all States and Union Territories in the country

- It is 85% of the total population (2011 census)

- 13 tribes have been identified as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs)

- The PVTGs have 500 habitations in the state and most of them are located in forested hills.

Juang tribe

- The Juang tribe, one of the PVTGs, belongs to the Munda ethnic group

- They live in Keonjhar, Dhenkanal, Angul and Jajpur districts of Odisha

- They speak Juang language, which is accepted as a branch of the greater Austroasiatic language family

- Many who come down the hill can also speak Odia

- A Juang Development Agency (JDA) was established in 1975 at Gonasika Hills in Keonjhar district.

- Objective: to bring Juangs into the mainstream

- After four decades: the agency has not been able to go beyond the Juangs of Keonjhar. It operates in 35 villages in six gram panchayats of Banspal block of Keonjhar. 20 more villages are yet to be covered.

- Many other Juang-dominated villages in Harichandanpur block of Keonjhar, Kankadahad block of Dhenkanal have remained outside the purview of the JDA all these decades

- Juang people live in the hamlets atop Nagada hills — Tala Nagada, Majhi Nagada, Upara Nagada, Tumuni, Naliadaba, Guhiasala and Taladiha.

How do they survive?

- The children and the adults of the Juang tribe at Nagada have very feeble health

- They live in one room huts with minimal clothing, few kilos of ration rice and some maize that is grown near home.

- The able men and women of these hamlets climb down the hills and walk down 20 km at least once a month to buy ration rice from the gram panchayat office at Chingudipal or anything from the weekly haat (market) near Kaliapani.

- Rice and salt is their staple food.

- As the quantum of rice is not sufficiently available for the entire family, the tribes eat boiled wild tuber collected from forests

- They are deprived of basic facilities such as drinking water, primary health care, electricity, and primary education available under various Central and State schemes. Main reason is inaccessibility.

- There is not a single well in these hamlets and they depend on forest streams for water throughout the year.

- Many residents in these don’t even have voter IDs and job cards under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme

- None of the families have been given land rights under the Forest Rights Act.

- Official survey by State Women and Child Development Department

- 44 children in the age group of six months to five years were suffering from malnutrition in the seven hamlets atop the Nagada hills

- Nine more such children had been identified in Ashokjhar, another Juang hamlet situated in the foothills

- 24 of the 53 children are suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and the remaining are suffering from moderate acute malnutrition (MAM)

- The SAM and MAM children are identified by the measurement of upper arm muscles along with body weight.

- Only in last November, informal education began in Nagada when Aspire, a non-governmental organisation, started a non-residential bridge course for 100 children, with financial support from Tata Steel Rural Development Society.

- Astonishingly, the CSR funds from nearby mining are not utilised for tribals in Nagada

- Instead, they are supporting Aahar outlets run by state government in district headquarters, towns and cities.

2013 tragedy

- In Lahunipara block of Sundargarh district, 200 km from Nagada, several malnourished Paudi Bhuyan tribal children had allegedly died of diseases caused by acute malnutrition.

- There is no official record on it, but a food rights activist claims that about 15 deaths were reported from different villages in Lahunipara

- After the Paudi Bhuyan tribal incident, the State Women and Child Development Department, in consultation with Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes, health and family welfare, rural development and panchayati raj departments, prepared a guideline for a convergent health and nutrition plan to address the health and nutritional needs of PVTGs in the State.

- As per an official survey, as many as 195 children belonging to Paudi Bhuyan tribe were suffering from severe malnutrition in Lahunipara in 2013

- The challenge

- Many deaths due to malnutrition go unreported in such hamlets due to their

- Death due to malnutrition is not what health officials want to be recorded

- Also, the exact reason of children’s death is not known as parents quickly bury their little ones.

The connectivity Issue

- From Nagada hills, the nearest hospital is the Tata Steel hospital, 27 km away.

- The Tata Steel hospital is to cater the needs of its employees at Sukinda chromite mine

- The government -run public health centre is 36 km away in Kuhika

- The community health centre at Sukinda is 46 km away

- The district hospital is 110 km away

- There exists an Anganwadi at the foothills of Nagada.

- The incharge supplies packets of nutritional chhatua, a mix of Bengal gram, wheat, peanut and sugar, to the villagers whenever they come down.

- However, ideally, there has to be an anganwadi at the top of the hills which has the responsibility to supply the essentials as well as weigh the children and administer their food intake

- The nutrition needs of PVTG along with their road connectivity issues remain unaddressed.

Where are the welfare schemes?

- The Nutrition Operational Plan was drawn up in 2009 to accelerate the pace of underweight reduction in Odisha because

- 38% of children in Odisha are stunted

- 46% of the tribal children in Odisha are stunted

- This raises the question on efficiency of plans and welfare schemes rolled out by government for tribals living in inaccessible areas

- Also, the PVTGs are not under the ambit of National Food Security Act.

- Majority of tribal families have ration cards but they don’t have Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) cards despite SC ruling that all households which belong to six priority groups including PVTGs, would be entitled to AAY cards.

- Thus, not only geographical isolation but also exclusion from many government schemes have made children suffer from acute malnourishment.

Administration comes in action

- Two local newspapers, Samaja and Sambad along with local television reports about 19 deaths of children due to malnourishment made the government realise the grave situation

- Following the reports, various political parties are making a visit to Nagada

- A field level task force and a State-level monitoring committee has been formulated by state government to keep a close watch

- At present, there have been 50 officials posted on rotational basis with temporary arrangements of cots and tents, medicines and food material for a mini-makeshift anganwadi, solar lights, water filters and saplings of nutritious fruits and vegetables.

- Result: 22 malnourished children under the age of six have been hospitalised in Tata Steel hospital.

- The children were kept under observation for a week as most of them suffered from malaria, chest congestion and acute malnutrition. All of them survive today.

- Today, the State administration is working overtime to build roads to Nagada using Integrated Action Plan funds by involving the Forest and Rural Development departments. There are plans to build roads from the Jajpur as well as Dhenkanal sides.

- Further, an initiative has been taken by government to identify all inaccessible tribal hamlets across the State. This is done by

- Assimilating information from the district administrations

- Using remote sensing data from Odisha Space Applications Centre

Conclusion

- Though the Chief Minister has assured of no such critical incidents in future, mere words won’t suffice.

- The need of the hour to bring all PVTGs living atop forested hills in the State under the welfare programmes

- The officials have been trying to convince the tribal people to rehabilitate to plains. However, the tribes refuse to so. And hence, the officials should focus more on increasing connectivity than to uproot tribes from their homes.

- Even in difficult topography and climatic conditions, development projects are successfully established. Then, bringing development in form of education and health and nutrition to these tribes at their footsteps should not be a difficult and impossible task.

Connecting the dots:

- Malnutrition is the critical challenge to India’s economic and social development. Critically analyse

Refer:

India: Epicentre of Global Malnutrition

Despite bar, private players continue in nutrition scheme

India needs a nutrition mission

Social Progress Index: A work in progress

ENVIRONMENT

TOPIC: General Studies 3

- Environment and Ecology, Bio diversity – Conservation, environmental degradation, environmental impact assessment, Environment versus Development

‘Combat Desertification’

What is Desertification?

- The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification defines the term desertification as ‘land degradation in arid, semi-arid and sub-humid areas resulting from various factors including climatic variations and human activities’.

- Desertification is a dynamic process that is observed in dry and fragile ecosystems. It affects terrestrial areas (topsoil, earth, groundwater reserves, surface run-off), animal and plant populations, as well as human settlements and their amenities (for instance, terraces and dams).

Indian definition:

- The process of fertile land transforming into desert typically as a result of deforestation, drought or improper agriculture is called desertification. Desertification in India is essentially a result of soil degradation because of various physical, chemical & biological factors.

Causes of Desertification in India

Desertification in India is caused by complex interactions among physical, biological, political, social, cultural and economic factors. Both natural and anthropogenic causes are responsible for the desertification in India.

- Natural causes such as climate change, droughts, and soil erosion are enhancing the pace of desertification.

- Anthropogenic causes include flawed and unsustainable practices of agriculture such as shifting cultivation, excessive use of chemical rertilizers, poor irrigation practices, deforestation and expansion of agriculture areas are main causes of desertification.

- Industrial waste, which is full of toxic chemicals, is a major dause of land pollution. This ultimately results in desertification.

- Climate change could be one of the reasons for Desertification in India. Climate change is affecting the Indian monsoon. In that affect, the rainfall pattern in the country is changing and frequency of droughts is increasing.

Desertification in India and its impacts:

- According to a study by United Nations Convention to Control Desertification (UNCCD) about 25% of India’s land area is affected by desertification.

- In other words, a whopping 25 per cent (82 million hectares) of India’s total land (329 mn ha) is undergoing desertification while 32 per cent (105 mn ha) is facing degradation that has reduced productivity, critically affecting the biodiversity, livelihood and food security of millions across the country.

Desertification affects Biodiversity:

Biodiversity of India has always been integral to its culture. Globally, nearly 70 per cent of the world’s biodiversity is contained in just 17 countries, and India is one of them.

Unfortunately, these assets are under threat due to

- decline in habitat area and its deterioration due to desertification;

- drying up and pollution of surface and groundwater sources;

- conversion of forests and grasslands to agriculture and monoculture plantations; and

- invasion by exotic species

Desertification affects Food Security

- Land has been rampantly abused and mined by humans, rendering it dry, nutrition deficient and unproductive.

- Water scarcity can result in low productivity and crop failure, leading to food shortage, price rise and subsequent hunger.

- Loss of indigenous stress tolerant crop varieties weakens the battle against adequate food production.

- According to the UN, food output must grow by 60 per cent to feed a population of nine billion or more by 2050. In a world already grappling with addressing the hunger challenge, this will pose a serious threat to food security, since ‘more’ will have to be produced with ‘less’.

Water woes

Water plays a dual role in desertification.

- Its scarcity leads to desertification: Worsening droughts in India are having an impact on the desertification trend. Vegetation dries up and is rarely replaced.

- In the absence of a good vegetative cover, torrential rains cause substantial loss of soil which is flushed away.

- Then the land dries a hard crust is formed on the surface leading reducing water infiltration and leading to subsequent water scarcity. At last count, the 2016 drought in India has affected 330 crore people across 10 States.

Solutions:

With water playing such a critical role in overall natural resource management, grass root practitioners suggest that “we must teach the running water to walk, the walking water to halt and then arrange for this water to find its way into subsoil and underground aquifers”.

Coupled with the plantation of local species including trees and practising agriculture suited to the ecology, results are heartening.

- In Jalaun district of Uttar Pradesh, part of the Bundelkhand region, farmers are planting traditional varieties.

- In Andhra Pradesh, the Deccan Development Society is working with around 5,000 women farmers to cultivate food grains that are suited for the ecology and also maintain local varieties of crops.

It is important to promote ecological agriculture.

- However, one of the main challenges in promoting ecological agriculture is to find the market. Millets and coarse grains were once scoffed at as a poor person’s diet, but they now command a premium price. Similar efforts should be made to popularise benefits of local ecology-friendly agricultural produce.

In fact, most watershed programmes are a mix of land and water management practices with many of them proposing vegetation cover and cultivation of native species.

Effective prevention of desertification requires management and policy approaches that promote sustainable resource use. Prevention should be preferred to rehabilitation, which is difficult and costly.

Major policy interventions and changes in management approaches, both at local and global levels, are needed in order to prevent, stop or reverse desertification.

International cooperation and partnership arrangements to combat desertification:

- June 17, 2016: was earmarked as the World Day to Combat Desertification.

The day advocated for ‘the importance of inclusive cooperation to restore and rehabilitate degraded land and contribute towards achieving the overall Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs)

- Goal 15 of the SDGs: is to ‘Protect, restore and promote sustainable terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.’

(This goal is linked with practically all the other goals, be it on poverty alleviation, ending hunger, reducing inequality, gender or employment.)

- UNCCD: The purpose of the 1994-adopted United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification is to combat desertification and mitigate effects of drought through national action programmes that incorporate long-term strategies supported by international cooperation and partnership arrangements.

The Convention is an agreement between developed and developing countries on the need for a global team effort to address desertification. It includes specific national commitments for concrete action at the local level where the combat against desertification must primarily and vigourously be fought.

Conclusion

In the true spirit of cooperation and partnerships, in line with Goal 17 of the SDGs (Revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development), and the theme for this year’s World Day to Combat Desertification, there is lot that countries can learn from each other.

Many organisations are involved in knowledge exchange between developing countries. While India has its share of good pilots to address desertification these need to be up scaled and spread laterally since the problems continue to be serious. The country can also learn from innovations elsewhere.

- But there is a rider. No matter what the science, technology, or political will, unless the people are involved in the process, results will never commensurate with the investment.

- US President Franklin D Roosevelt once said, “A nation that destroys its land, destroys itself.” Each one of us should take stock and move forward towards conservation and judicious use.

The creation of a “culture of prevention” that promotes alternative livelihoods and conservation strategies can go a long way toward protecting drylands both when desertification is just beginning and when it is ongoing. It requires a change in governments’ and peoples’ attitudes. Building on long-term experience and active innovation, dryland populations can prevent desertification by improving agricultural and grazing practices in a sustainable way.

Even once land has been degraded, rehabilitation and restoration measures can help restore lost ecosystem services. The success of rehabilitation practices depends on the availability of human resources, funds, and infrastructures. It requires a combination of policies and technologies and the close involvement of local communities.

Efforts to reduce pressures on dryland ecosystems need to go hand in hand with efforts to reduce poverty as both are closely linked. Effectively fighting desertification will help reduce global poverty and will contribute to meeting the Sustainable Development Goals.

Connecting the dots:

- Essay: “A nation that destroys its land, destroys itself.”

- Examine the causes and the extent of ‘desertification’ in India and suggest remedial measures.

- What is desertification? What are the causes of desertification in India? Suggest some measures to stop the process of desertification in India

MUST READ

Retrofitting the Reserve Bank

Not a full-fledged State

Related Articles:

GST: A constitutional adventure

Safety Valve For Defectors

Fresh monsoon air? There’s no such thing

A desert storm is engulfing India