IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs July 2017, IASbaba's Daily News Analysis, National, UPSC

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 26th July 2017

Archives

NATIONAL

TOPIC:

General Studies 1:

- Urbanization, their problems and their remedies.

General Studies 2:

- Important aspects of governance, transparency and accountability, e-governance- applications, models, successes, limitations, and potential; Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

Financing Indian Cities

Introduction:

Cities are the engines of economic growth. Owing to a variety of factors ranging from availability of skilled manpower to the benefits of agglomeration, much of India’s future growth is expected to come from its cities. By 2030, India’s cities are expected to contribute nearly 70% of the GDP, according to a McKinsey Global Institute analysis. However, very little investment goes back into those very cities.

Financial health of Indian cities:

Cities are under-invested:

India’s annual per capita spending on cities, which stands at $50, is 14% of China’s $362, 10% of South Africa’s $508 and less than 3% of the U.K.’s $1772. The inevitable outcome of that under investment is bad infrastructure and poor quality of life.

These crippling infrastructure deficits matter not just because they cause hardships to residents, but because India’s economic growth itself could be under threat. If cities are unlivable, the benefits of agglomeration would hardly kick in and India would miss its narrow window of opportunity to develop rapidly.

- A 2010 McKinsey report estimates that India will need to spend $1.2 trillion by 2030, a far cry from current spending estimates.

- The financial health of Indian cities is in such a pathetic state that revenue generated by urban local bodies accounts for less than 0.9% of the total GDP (gross domestic product) despite cities contributing almost 60% towards GDP.

- Several urban local governments have to also rely on state governments to fund even basic operational expenditure like employee salaries.

- In tier 2 and tier 3 cities, urban local bodies and municipal corporations have had little or no autonomy or capacity to raise revenue.

- The government’s flagship urban development schemes fund only a fraction of the required investment and cities are tasked with finding other ways to bridge the funding gap. For example, under the Smart Cities Mission, the government has allocated $15 billion for 100 cities to be disbursed over four years, with equal contributions from the Central and state governments. This amount is by no means sufficient. The grant is to be seen as a starting point to attract funding from external sources.

India’s spending on urban infrastructure has to increase eight-fold. But much of this money may not come from the Central government. Cities themselves have to figure out ways to raise the money. However, the current revenue base of municipalities is narrow, inflexible and non-buoyant (meaning, it does not increase in step with the economy, unlike, say, a service tax).

Issues:

- Over the last decade, public-private partnerships (PPPs) have been the preferred route for infrastructure creation in India. But PPPs have not worked as well as they were expected to owing to the poor rate of return for the private sector and other inefficiencies. The PPP model needs a radical redesign to be able to account for regulatory uncertainty and financial risk, a fact acknowledged by even the Kelkar committee appointed to study how the PPP model can be revived.

- With the banking system heavily stressed with bad debts, urban rejuvenation might not receive the necessary impetus from the private sector in the short term.

The underlying lesson is that the government cannot afford to wholly rely on the private sector and will have to boost public spending as well as generate revenue on its own.

What needs to be done?

The government must commit to developing a city’s creditworthiness.

Municipal bonds:

Credit rating of cities is the first step towards raising money through the bond market, subnational governments, and international lenders. Ratings are assigned based on the assets and liabilities of urban local bodies, revenue streams, resources available for capital investments and implementation of credible double-entry accounting mechanisms.

More recently, the government announced that 94 of the 500 cities have already obtained such ratings, necessary for issuing municipal bonds. However, only 59% of the cities assessed were found to be worthy of investment.

Cities rated AA are considered safe investments and may access the market directly without any intervention. Most of the metropolitan cities fall under this category. Cities rated A and BBB are less desirable in comparison but are still considered worthy of investment. However, these cities may need some sort of financial cushioning from the government.

Cities rated BB and below may find it difficult to raise funds. Even if they do manage to elicit investments, these are bound to come at much higher rates of interest, which might be economically infeasible.

As the bonds are not tax-free, the government is considering setting up an interest subsidy fund of Rs400 crore to offset the high interest rate.

Despite the optimism and investor appetite, municipal bonds may prove to be successful only in fast-growing metropolitan cities. Pune is on the verge of raising Rs2,300 crore, an amount well over what has been collected so far cumulatively by all cities till date. Ahmedabad, New Delhi, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Chennai might follow soon.

Other ways of financing cities:

- Over the last decade, property prices in tier 2 and tier 3 cities have been on a steady upward trajectory. Against this backdrop, a move worth pursuing is the deployment of land value capture instruments. When a government invests in developing a particular area—for example, building a new airport outside a city—land prices around the area rise. A portion of this benefit could accrue to the government either through betterment charges, tax increment financing, developer extractions, or impact fees. Several states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat and West Bengal are slowly beginning to explore this instrument as a method to generate revenue.

- Cities should be able to access a broad portfolio of taxes such as motor vehicle tax, professional tax, fuel tax, excise, business and financial taxes, entertainment tax, etc., all of which are currently appropriated by state governments. This would involve amending the Constitution to have these taxes included in the municipal finance list. Inclusion of a city GST (goods and services tax) rate within the state GST rate, a formula-based mechanism to ensure municipalities get their share.

- Most Indian cities tax built form through a property tax, but the windfall increases in the monetary value of land as a result of provisioning taxpayer-funded public infrastructure in the vicinity is mostly not taxed. The costs of providing water and sewer lines, as well as public roads, can be recovered from developers through a combination of land tax, development charges and betterment fees.

- A rational user charge scheme for the continued provision of public services like water supply, with a fairly priced monthly lifeline charge for the poor and a graded increase in charges (based on usage) to ensure the rich don’t end up getting subsidised.

Lack of fund is not the only concern:

India suffers from a serious local democracy deficit. Without fixing that, throwing money at the problem may not help. Without serious introspection about the nature of our urban democratic governance, innovative taxes and user charges may not help much. The real opportunity that Indian cities offer is a chance to build a better democracy, where there is considerable local autonomy and government spending is transparent and accountable.

Conclusion:

The reforms outlined above require immense political will and a real understanding of the problems cities face. Unfortunately, despite being the breadwinners of the economy, Indian cities have seldom been able to assert themselves strongly enough. Its time we focus on makig our cities creditworthy.

Connecting the dots:

- Cities across the world are seen as engines of growth. However, given the fact that Indian cities are under-invested it may not be the case in India. Critically analyze.

NATIONAL

TOPIC: General Studies 1:

- Parliament and State Legislatures – structure, functioning, conduct of business, powers & privileges and issues arising out of these.

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

Gorkhaland movement is a question of identity, not development

About Gorkhaland movement

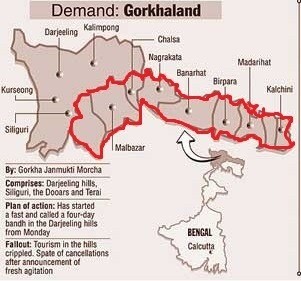

The Gorkhaland movement is a long-standing quest for a separate State of Gorkhaland within India for Nepali-speaking Indian citizens (often known as ‘Gorkhas’).

Link: https://qph.ec.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-724265ce1b8508ea0385285df3584912-c

With roots dating back over a century, Gorkhaland is a classic subnationalist movement, not unlike those that have produced other States, most recently Telangana, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh. Beyond all else, Gorkhaland is a desire for the recognition, respect, and integration of Gorkha peoples in the Indian nation-state. Contra popular misunderstanding, the movement is neither separatist nor anti-nationalist; it is about inclusion and belonging in India.

Gorkhaland consists of Nepali-speaking people of Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Kurseong and other hilly districts. The people belonging to these areas hardly have any connection with the Bengali community and are different in ethnicity, culture and language.

History of Gorkhaland movement: A look back

History has it that the demand for Gorkha autonomy and a separate state dates back to more than a century and could be one of the oldest in the country.

- Prior to 1780 – was under control of Chogyals of Sikkim.

- In 1780 – the Gorkhas of Nepal captured Sikkim and most part of North Eastern states that includes Darjeeling, Siliguri, Simla, Nainital, Garhwal hills, Kumaon and Sutlej, that is, the entire region from Teesta to Sutlej.

- Treaty of Sagauli, 1816 (Anglo-Nepal War) – Gorkhas surrendered the territory to British EIC after they lost the Anglo-Nepal war.

- Treaty of Titalia, 1817 – British handed over Darjeeling to Chogyals of Sikkim.

- In 1835 – It was taken back for political reasons by British EIC.

- Till 1866 – Political iterations continued till, when Darjeeling finally assumed its present shape.

- Before 1905 partition of Bengal (by Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon) – Darjeeling was a part of Rajshahi division, which now falls in Bangladesh.

- 1905-1912 – For a short period it was even a part of Bhagalpur division.

Timeline of the Gorkhaland crisis:

- 1907 – The first demand for Gorkhaland is submitted to Morley-Minto Reforms After that on several occasions demands were made to the British government and then government of Independent India for separation from Bengal.

- 1952 – The All India Gorkha League submits a memorandum to then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru demanding separation from the state of Bengal.

- 1955 – Demands State Reorganisation Committee for the creation of separate state consisting of Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri and Cooch Behar district.

- 1977- 81: The West Bengal government passes a unanimous resolution supporting the creation of an autonomous district council consisting Darjeeling and related areas.

- In 1981, the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi receives a memorandum from Pranta Parishad, demanding a separate state.

- 1980-90: The demand for Gorkhaland was intensified in the 1980s under the leadership of Gorkha National Liberation Front supremo Subhas Ghising. The movement turns violent during the period of 1986-88, and around 1,200 people are killed. After a two-year long protest, the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC) is finally formed in 1988.

- 2007 – At the last phase of left front’s regime, the mass movement for Gorkhaland takes place under the leadership of Gorkha Janmurti Morcha (GJM) supremo Bimal Gurung.

The 2007 Gorkha uprising intensifies, following the 2005 Centre and state government initiative for a permanent solution of this region by bringing it to the sixth schedule of the constitution giving some degree of autonomy to a predominantly tribal area. But the Gorkhas opposed this sixth schedule and demand statehood gains pace.

The then CM (Mamata Banerjee) declarates Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA) and Gurung was made its leader.

- 2013 – With the formation of Telangana on July 20, 2013, the movement for Gorkhaland state again intensifies. Gurung resigns from the head of GTA, says people have lost all faith.

- July 2017 – The West Bengal government’s decision to impose Bengali language in all the schools from Class I-IX, has sparked a violent protest in the Gorkha-led Darjeeling.

Darjeeling unrest: Gorkhaland movement is a question of identity, not development

- The core issue behind the ongoing agitation in Darjeeling, (to break away from West Bengal and for the creation of a separate state called Gorkhaland), is identity, not development.

- Gorkhaland consists of Nepali-speaking people of Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Kurseong and other hilly districts. The people belonging to these areas hardly have any connection with the Bengali community and are different in ethnicity, culture and language.

- Language has always been a contentious issue in the hills of Darjeeling and the state has ‘used’ the census as a tool to portray Nepali speakers as minority in these areas, even though they happen to be in a majority. The Nepali language movement of the 1960s in the hills has been a manifestation of this cultural trend.

- The West Bengal government, along with the central government, played the politics of census enumeration in identifying Nepali as a non-majority language so that they could avoid making Nepali the medium of instruction in schools in Darjeeling.

Moreover, the perceived cultural dominance of Bengalis in the hills widened the gulf between these two communities.

Why Gorkhaland Movement Matters?

- It is one of the oldest movement in India (began in 1907)

- What happens in Gorkhaland will affect India-Nepal relations too. How India treats the problems of the Nepali people of hill origin in Darjeeling will affect how Nepal deals with the people of Indian origin in Nepal, i.e. Madhesi in Terai.

- Gorkhaland has a strategic location, it’s vicinity to the chicken neck that connects rest of India with North East. Its stability is must for India’s strategic and economic interests of the nation.

- Darjeeling is a tea and tourist hot-spot with a high level of poverty. It needs and has potential to become the economic engine of the East with a sustainable economic model. But such things will be possible only if there is stability in the region.

Creation of Gorkhaland: Pros and Cons

Pros:

- The Gorkhaland Movement is neither a fight against Bengal nor is it hatred against Bengalese. Once the STATE OF GORKHALAND is formed, no other INDIAN can call the GORKHA a FOREIGNER. The IDENTITY of the Gorkhas as Indians will become secured.

- It may create a stable and responsible government in Darjeeling.

- It will end one of the longest movements for the creation of a separate state in India.

Cons

- It can lead to “Balkanization” of India.

- It may legitimise violence as a way to meet demands.

- The rise of agitation with the rise of new outfits shows that politics plays the vital role. The division would be an extreme measure for a problem that can be resolved by political consensus like done in 1988 and 2011.

- Division of state should be done on the criteria set by State Reorganization Commission. Any diversion would only create a more dissension than the solution.

Conclusion:

The demands for separate statehood in India have been there even before India’s Independence. Even after the state re-organization of 1956, there were demands from various corners of the country for the creation of a separate state. Linguistic, cultural, ethnic and economic distinctions can be traced as the core reasons behind these demands.

Heralding self-governance, recognition, and belonging in India, Gorkhaland remains the dream for Darjeeling citizens and many Nepali-speaking Indians across the country. It stands as a key means to redress the Gorkhas’ enduring history of discrimination, misconception, and marginalisation in India.

The basic point about Gorkhaland is IDENTITY and NOT DEVELOPMENT. By demanding Gorkhaland, the people of Darjeeling-Kalimpong are opting out of West Bengal’s domination, and opting in to the democratic frameworks of India writ large.

Hegel said, “We learn from history that we do not learn from history”. The repetition of history in the Gorkhaland issue is the living proof. Especially in the post-independence, where the rise and fall of momentum in demand follow the rise and fall of the party involved. The solution lies in pleasing the population rather than the parties. Gorkhaland can become an epitome of decentralisation or a failed divided state. The choice is in the hands of people protesting. Are they protesting for the right cause?

Connecting the dots:

- Recently separate statehood movement got renewed and intensified in Darjeeling district of West Bengal. Critically analyze the reasons behind the demand and also discuss if creation of another state would help bring stability in the region.

- What led to the revival of Gorkhaland Demand? What are the possible solutions?

- Discuss the roots and causes of the current Gorkhaland agitation in Darjeeling. Critically analyze the pros and conservation upon creating a separate Gorkhaland.

- Is under-development driving the demand for Gorkhaland. Critically examine.

Also refer:

http://iasbaba.com/2017/06/iasbabas-daily-current-affairs-20th-june-2017/

http://iasbaba.com/2017/07/rstv-big-picture-led-revival-gorkhaland-demand-possible-solutions/

MUST READ

Context of the contest

The crossroads at the Doklam plateau

In the age of data

For a hygienic track

Dancing on the edge

A grievous lag

A New Social Anthem

Back to waste basics

Brokering the social contract in India’s slums

India-Africa ties: Economics and Multilateralism

Are university rankings reliable?