The Big Picture- RSTV, UPSC Articles

ASER – Annual Status of Education Report 2019

Archives

TOPIC: General Studies 2:

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

- Issues relating to development and management of Social Sector/Services relating to Education

In News: The recently released ASER 2019 report by NGO Pratham is completely focussed on exploring more deeply where young children are and what they can do. It directs attention to children between four and eight years of age, and suggests that India’s learning crisis could be linked to the weakness of the country’s pre-primary system. The report is based on a survey conducted in 26 districts across 24 states in India, covering over 36,000 children in the age group of 4-8 years.

- More than 20 per cent of students in Standard I are less than six

- 36 per cent students in Standard 1 are older than the RTE-mandated age of six – close to five crore children currently in elementary school do not have foundational literacy and numeracy skills

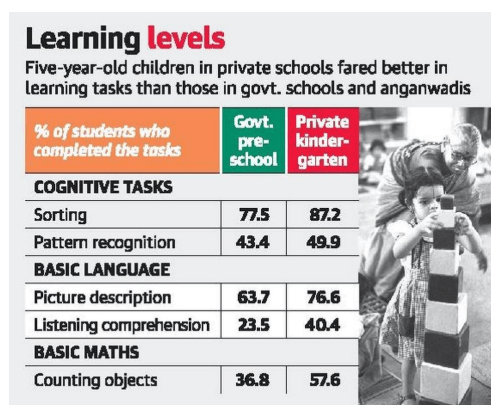

- Gender gap in schooling: Parents choose government schools for girl students in the age group of 4 to 8 years while for boys, they prefer private schools – among 4-5-year-old children, 56.8 per cent girls and 50.4 per cent boys are enrolled in government schools or pre-schools, while 43.2 per cent girls and 49.6 per cent boys are enrolled in private pre-schools or schools

- Across all age groups enrolled in standard I, girls in private schools are performing better than their male counterparts

The emphasis, as ASER 2019 emphasises, should be on “developing problem-solving faculties and building memory of children, and not content knowledge”.

ASER – Annual Status of Education Report 2019 – Vishesh – RSTV IAS UPSC

The mother’s education often determines the kind of pre-schooling or schooling that the child gets. How?

The report says that among children in the early years (ages 0-8), those with mothers who had completed eight or fewer years of schooling are more likely to be attending anganwadis or government pre-primary classes, whereas their peers whose mothers had studied beyond the elementary stage are more likely to be enrolled in private LKG/UKG classes.

ASER 2019 also shows how, among 4- and 5-year-olds who were administered a four-piece puzzle and 6- to 8-year-olds who were asked to solve a 6-piece puzzle, those whose mothers had completed Class 11 or more had a higher chance of solving these cognitive tasks.

Between 2011 and 2012, researchers at MIT’s Poverty Action Lab worked with Pratham to study whether literacy classes and other interventions for mothers could improve children’s learning outcomes. They found that their interventions have “had small positive impacts on mothers’ math and literacy skills, the home learning environment, some forms of school attendance, and ultimately children’s learning levels”.

But then why are children entering school before age six?

- This is partly due to the lack of affordable and accessible options for pre-schooling. Therefore, too many children go to Std I with limited exposure to early childhood education.

- Children from poor families have a double disadvantage — lack of healthcare and nutrition on one side and the absence of a supportive learning environment on the other.

- Although the anganwadi network across India is huge, by and large, school readiness or early childhood development and education activities have not had high priority in the ICDS system.

- Private preschools that are mushrooming in urban and rural communities have increased access to preschool but are often designed to be a downward extension of schooling. Thus, they bring in school-like features into the pre-school classroom, rather than developmentally appropriate activities by age and phase.

Trends that have emerged

First, there is considerable scope for expanding anganwadi outreach for three and four-year-old children. All-India data from 2018 shows that slightly less than 30 per cent children at age three and 15.6 per cent of children at age four are not enrolled anywhere. But these figures are much higher in states like Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Expanding access to anganwadis is an important incremental step. Strengthening the early childhood components in the ICDS system would help greatly in raising school readiness among young children.

Second, it is commonly assumed that children enter Standard I at age six and that they proceed year by year from Std I to Std VIII, reaching the end of elementary school by age 14. The Right to Education Act also refers to free and compulsory education for the age group six to 14. However, the practice on the ground is quite different. ASER 2018 data show that 27.6 per cent of all children in Std I are under age six.

Third, there are important age implications for children’s learning. Data from ASER 2019 (26 rural districts) indicate that in Std I, the ability to do cognitive activities among seven-eight-year olds can be 20 percentage points higher than their friends who are five years old but in the same class. In terms of reading levels in Std I, 37.1 per cent children who are under six can recognise letters whereas 76 per cent of those who are seven or eight can do the same. Interestingly, age distribution in Std I varies considerably between government and private schools, with private schools in many states having a relatively older age distribution. A big part of the differences in learning levels between government and private school children may be due to these differences in age composition right from the beginning of formal schooling.

The Way Forward

Understanding challenges that children face when they are young is critical if we want to solve these problems early in children’s lives rather than waiting till much later to attempt the much harder to do remedial action.

- On the pedagogy side, a reworking of curriculum and activities is urgently needed for the entire age band from four to eight, cutting across all types of preschools and early grades regardless of whether the provision is by government institutions or by private agencies. A case can also be made for streamlining the curriculum at the pre-school stage so that all pre-schools focus on activities that build cognitive and early literacy and numeracy skills. These will aid further learning.

- There is a need to leverage the existing network of anganwadi centres to implement school readiness –

- The core structure of the anganwadis was developed more than 40 years ago as part of the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS). Pre-school education is part of their mandate. But at the best of times, these centres do no more than implement the government’s child nutrition schemes.

- A number of health crises — including last year’s AES outbreak in Bihar — have bared the inadequacies of the system. A growing body of scholarly work has also shown that the anganwadi worker is poorly-paid, demoralised and lacks the autonomy to be an effective nurturer.

- There is a need to expand and upgrade anganwadis to ensure that children get adequate and correct educational inputs of the kind that are not modeled after the formal school.

- Most of the young mothers in the next decade will not be very young as median age of marriage has increased from 18.2 years in 2001 to 19.2 in 2011 to nearly 21.7 in rural India and 23.4 in urban India by 2016. Further, most of these young mothers will have had at least five years of schooling. These changes in the young Indian mother’s profile need to be taken into account when thinking of the education inputs to be designed for the Indian child of the next decade.

“The idea behind early childhood education is not more institutionalisation in the form of private pre-schools or play schools but to involve children through cognitive tasks that mainly involve play.”

Connecting the Dots:

- Early childhood education has the potential to be the “greatest and most powerful equaliser”. Discuss.