UPSC Articles

ECONOMY/ GOVERNANCE

- GS-3: Issues related to direct and indirect farm subsidies

- GS-2: Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

Controlling the Subsidy bill

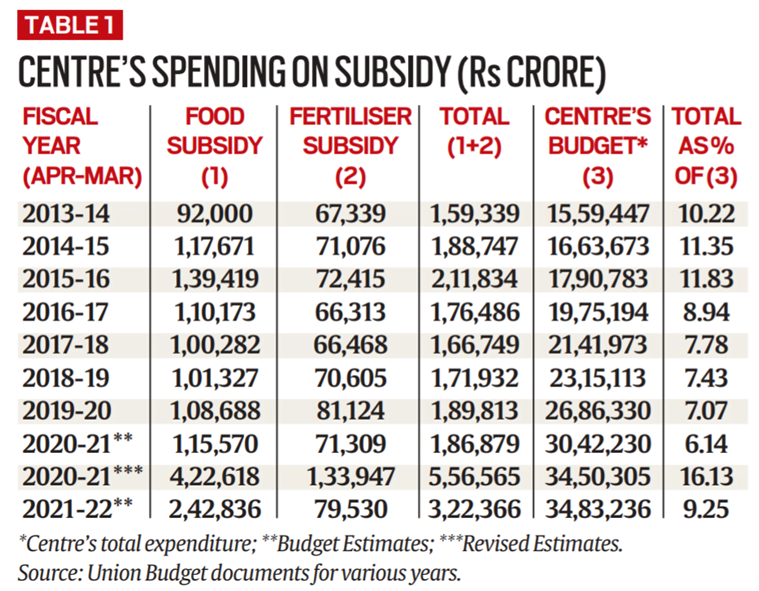

Context: Between 2015-16 and 2019-20, the aggregate outlay on food and fertilizer subsidy fell, both in absolute terms (from Rs 211,834 crore to Rs 189,813 crore) and as a share of the Centre’s total expenditure (from 11.8% to 7.1%).

- A further drop, to Rs 186,879 crore and 6.1%, was projected in the Budget for 2020-21.

- That declining trend has, however, since completely reversed.

- The combined food and fertiliser subsidy bill in the revised estimates for 2020-21 was a massive Rs 556,565 crore, representing 16.1% of the Centre’s entire Budget (Refer image below)

What are the reasons for the reversal in 2020-21?

First reason is government coming clean in food & fertilizer subsidy bill

- The first has to do with the Centre, until 2021, not providing fully for the subsidy, arising from FCI’s subsidies and fertiliser firms selling nutrients at below cost to farmers.

- In the case of food, the Centre wasn’t wholly funding the difference between the FCI’s economic cost and its average issue price, multiplied by the quantities sold.

- FCI’s economic cost includes costs of procuring, handling, transporting, distributing and storing grain.

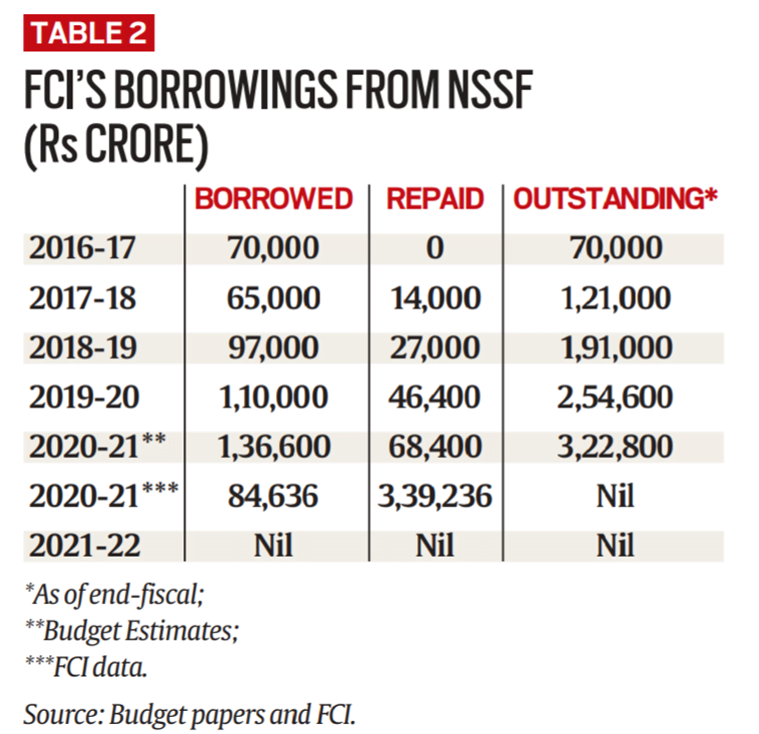

- To bridge the gap, FCI had to borrow heavily, especially from the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF), with interest rates ranging from 7.4% to 8.8% per annum.

- FCI’s borrowings from NSSF in 2019-20, at Rs 110,000 crore, exceeded the food subsidy of Rs 108,688 crore provided through the Budget.

- Similarly in fertilizer sector, the industry was owed Rs 48,000 crore of subsidy dues at the start of 2020-21.

- But in the revised estimates for 2021-22, Finance Minister allocated an additional Rs 3,69,687 crore towards food and fertiliser subsidy. As a result, all outstanding NSSF loans to FCI got repaid and the fertiliser subsidy dues cleared at one go.

- This exercise of coming clean — the Centre owning up its expenditures, rather than transferring to the balance sheets of FCI and fertiliser companies — also meant a huge one-time spike in the subsidy bill.

Second reason is COVID

- The second source of overshooting has been Covid (in respect of food subsidy) and soaring international prices (vis-à-vis fertilisers).

- The post-Covid crisis led the Centre to not only distribute, but also procure, unprecedented quantities of grain. 5 kg of free grain/ person/ month was given under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY), apart from the regular 5 kg quota of wheat or rice at Rs 2 and Rs 3/kg, respectively.

- In 2020-21, a record 93.11 million tonnes (mt) of rice and wheat was sold through the PDS (62.19 mt, 65.91 mt and 60.37 mt in previous three years)

- A similar overshooting, despite no pending past dues, is expected in fertiliser subsidy. The primary reason is global prices. Urea imports into India are taking place now at $900-1,000 per tonne (nearly $300 in 2019-20) and di-ammonium phosphate at $900 (nearly $400 in 2019-20).

What is the way ahead for rationalising subsidy bill?

- Hiking PDS issue prices

- Capping grain procurement

- Decontrolling urea and providing a fixed per-tonne nutrient-based subsidy similar to that for other fertilisers.

Connecting the dots: