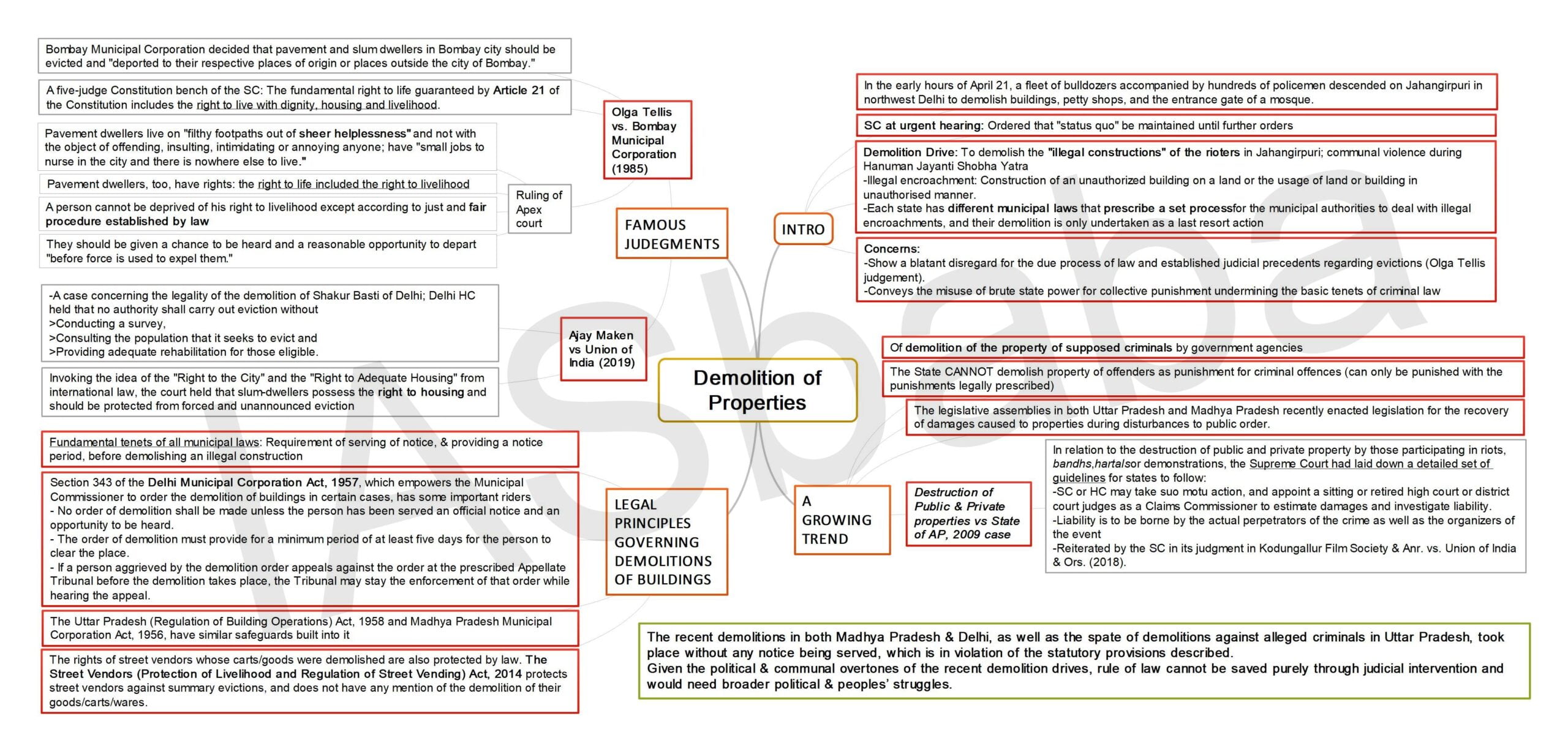

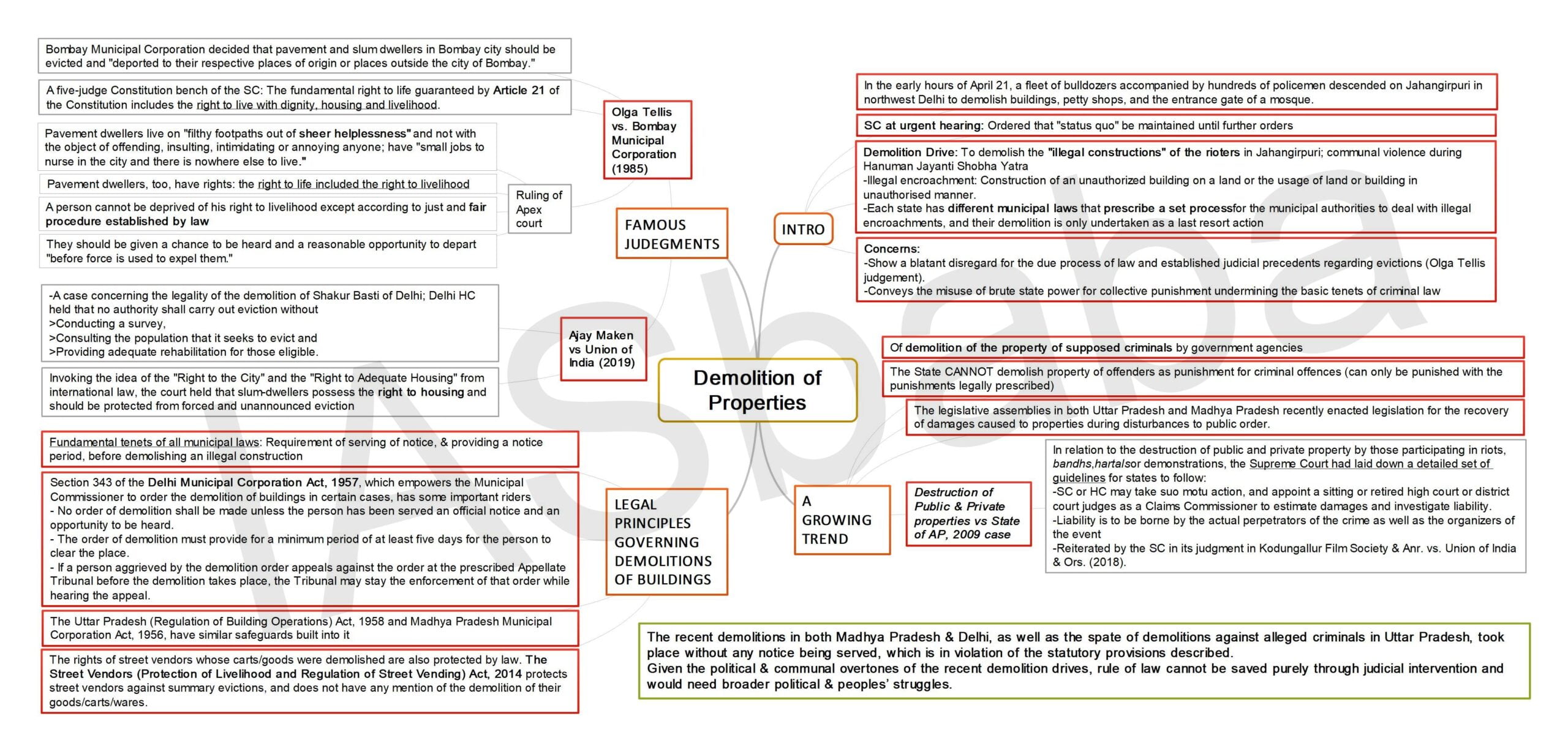

Baba’s Explainer – Demolition of Properties

Syllabus

- GS-2: Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation

- GS-2: Rights

Why in News: In the early hours of April 21, a fleet of bulldozers accompanied by hundreds of policemen descended on Jahangirpuri in northwest Delhi to demolish buildings, petty shops, and the entrance gate of a mosque. Soon after the demolitions started, the Supreme Court in an urgent hearing ordered that “status quo” be maintained until further orders.

- The demolition drive was initiated to demolish the “illegal constructions” of the rioters in Jahangirpuri.

- Communal violence had broken out in the area on April 16 when a Hanuman Jayanti Shobha Yatra (which did not have police permission) clashed with Muslims as it went alongside the mosque.

- Similar riot incidents, in Khargone in Madhya Pradesh and Khambhat in Gujarat had taken place, where processions during Ram Navami led to communal flare-ups.

- There is growing trend of demolition of the property of supposed criminals by government agencies where it becomes necessary to examine the legality of such actions.

Why did the demolitions occur?

- Technically and ostensibly, the recent demolitions in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Delhi were done to remove illegal encroachments from the land.

- An illegal encroachment is the construction of an unauthorized building on a land or the usage of land or building in unauthorised manner.

- Each state has different municipal laws regarding the usage of government and private land the violation which generally do allow the demolition of such encroachments.

- However, it is vital to note that these laws prescribe a set process for the municipal authorities to deal with illegal encroachments, and their demolition is only undertaken as a last resort action, when all other steps in the process have been extinguished.

Can the State demolish property of offenders as punishment for criminal offences?

- The short answer is NO.

- Criminal offences can only be punished with the punishments legally prescribed for those offences.

- There is no criminal statutory provision in the country that prescribes the demolition of an offender’s house as a penalty for any offence.

- Therefore, the narrative that the recent demolitions in Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Delhi are in response to the occupants of the demolished properties participating in communal clashes in these places, has no legal basis.

- The legislative assemblies in both Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh recently enacted legislation for the recovery of damages caused to properties during disturbances to public order.

- Neither of the legislation, or the any of the Supreme Court judgments (discussed below), mention anything to do with destruction of the property of the offenders.

Destruction of Public & Private properties vs State of AP, 2009 case

- In relation to the destruction of public and private property by those participating in riots, bandhs, hartalsor demonstrations, the Supreme Court had laid down a detailed set of guidelines for states to follow, in the absence of legislation, to assess damages and recover damages.

- As per the guidelines, Supreme Court or High Court may take suo motu action, and appoint a sitting or retired high court or district court judges as a Claims Commissioner to estimate damages and investigate liability.

- Further, the liability is to be borne by the actual perpetrators of the crime as well as the organizers of the event

- These guidelines were reiterated by the Supreme Court in its judgment in Kodungallur Film Society & Anr. vs. Union of India & Ors. (2018).

What are the concerns with recent demolition drives?

The actions of state and local authorities to bulldoze shops and homes in riot-hit Muslim neighbourhoods citing “illegal encroachment” raises major legal concerns.

- At one level, such actions show a blatant disregard for the due process of law and established judicial precedents regarding evictions (Olga Tellis judgement).

- At another level, it conveys the misuse of brute state power for collective punishment undermining the basic tenets of criminal law.

What was Olga Tellis vs. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985) Judgement?

- Bombay Municipal Corporation decided that pavement and slum dwellers in Bombay city should be evicted and “deported to their respective places of origin or places outside the city of Bombay.”

- State government had also argued these people cannot claim any fundamental right to encroach and put up huts on pavements or public roads over which the public has a ‘right of way.’

- A five-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court clearly stated in this case stated that the fundamental right to life guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution includes the right to live with dignity, housing and livelihood.

- It agreed that pavement dwellers do occupy public spaces unauthorised.

- The apex court ruled that pavement dwellers live on “filthy footpaths out of sheer helplessness” and not with the object of offending, insulting, intimidating or annoying anyone.

- They live and earn on footpaths because they have “small jobs to nurse in the city and there is nowhere else to live.”

- Pavement dwellers, too, have a right to life and dignity. The right to life included the right to livelihood. They earn a meagre livelihood by living and working on the footpaths.

- A person cannot be deprived of his right to livelihood except according to just and fair procedure established by law.

- A welfare state and its authorities should not use its powers of eviction as a means to deprive pavement dwellers of their livelihood.

- The procedure of eviction should lean in favour of procedural safeguards which follow the natural principles of justice like giving the other side an opportunity to be heard.

- The right to be heard gives affected persons an opportunity to participate in the decision-making process and also provides them with a chance to express themselves with dignity.

- Therefore, the court maintained they should be given a chance to be heard and a reasonable opportunity to depart “before force is used to expel them.”

Ajay Maken vs Union of India (2019)

- It was a case concerning the legality of the demolition of Shakur Basti of Delhi.

- Delhi High Court held that no authority shall carry out eviction without

- conducting a survey,

- consulting the population that it seeks to evict and

- providing adequate rehabilitation for those eligible.

- Invoking the idea of the “Right to the City” and the “Right to Adequate Housing” from international law, the court held that slum-dwellers possess the right to housing and should be protected from forced and unannounced eviction.

What are the legal principles governing demolitions of buildings, and were they followed?)

- One of the fundamental tenets of all municipal laws is the requirement of serving of notice, and providing a notice period, before demolishing an illegal construction.

- Section 343 of the Delhi Municipal Corporation Act, 1957, which empowers the Municipal Commissioner to order the demolition of buildings in certain cases, has some important riders.

- No order of demolition shall be made unless the person has been served an official notice and an opportunity to be heard.

- The order of demolition must provide for a minimum period of at least five days for the person to clear the place.

- If a person aggrieved by the demolition order appeals against the order at the prescribed Appellate Tribunal before the demolition takes place, the Tribunal may stay the enforcement of that order while hearing the appeal.

- The Uttar Pradesh (Regulation of Building Operations) Act, 1958 and Madhya Pradesh Municipal Corporation Act, 1956, also has similar kind of safeguards built into it.

- The rights of street vendors whose carts/goods were demolished are also protected by law.

- The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014 protects street vendors against summary evictions, and does not have any mention of the demolition of their goods/carts/wares.

- However, it has been widely reported that the recent demolitions in both Madhya Pradesh and Delhi, as well as the spate of demolitions against alleged criminals in Uttar Pradesh, took place without any notice being served, which is in violation of the statutory provisions described above.

Conclusion

Given the political & communal overtones of the recent demolition drives, rule of law cannot be saved purely through judicial intervention and would need broader political & peoples’ struggles.

Mains Practice Question – Can the State demolish property of offenders as punishment for criminal offences? Discuss.

Note: Write answers to this question in the comment section.

Mind Map

DOWNLOAD MIND MAP – CLICK HERE