Economics

Context: In his Independence Day address, Prime Minister asked Indians to embrace the “Panch Pran” — five vows — by 2047 when the country celebrates 100 years of independence.

- The first vow, is to become a developed country in the next 25 years.

What is a “developed” country?

- Different global bodies and agencies classify countries differently.

- The ‘World Economic Situation and Prospects’ of the United Nations classifies countries into three broad categories: developed economies, economies in transition, and developing economies.

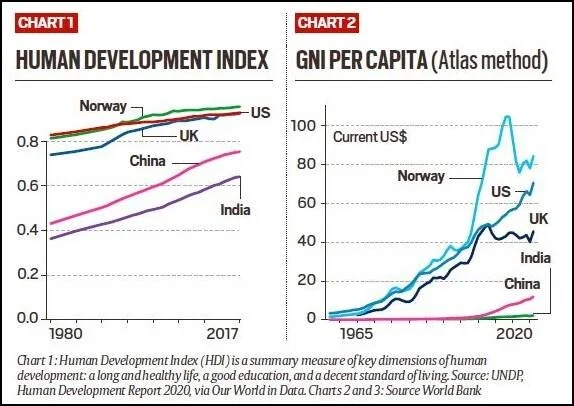

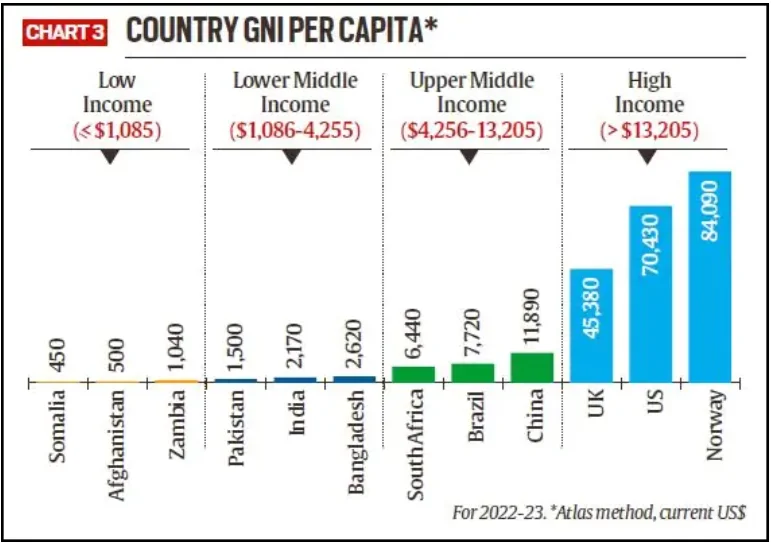

- To categorise countries by economic conditions, the United Nations uses the World Bank’s categorisation based on Gross National Income (GNI) per capita.

- But the UN’s nomenclature of “developed” and “developing” is being used less and less, and is often contested.

But why is the United Nations classification contested?

- It can be argued that the UN classification is not very accurate and, as such, has limited analytical value.

- Only the top three mentioned in chart 3 alongside — the US, the UK and Norway — fall in the developed country category.

- There are 31 developed countries according to the UN in all. All the rest — except 17 “economies in transition” — are designated as “developing” countries, even though in terms of proportion, China’s per capita income is closer to Norway’s than Somalia’s.

- China’s per capita income is 26 times that of Somalia’s while Norway’s is just about seven times that of China’s.

- Then there are countries — such as Ukraine, with a per capita GNI of $4,120 (a third of China’s) — that are designated as “economies in transition”.

Where does India stand?

- As chart 2 shows, India is currently far behind both the so-called developed countries, as well as some developing countries.

- However, to be classified as a “developed” country, the average income of a country’s people matters more.

- And on per capita income, India is behind even Bangladesh. China’s per capita income is 5.5 times that of India, and the UK’s is almost 33 times.

- The disparities in per capita income often show up in the overall quality of life in different countries.

- A way to map this is to look at the scores of India and other countries on the Human Development Index (HDI), a composite index where the final value is reached by looking at three factors: the health and longevity of citizens, the quality of education they receive, and their standard of life.

- India has made a secular improvement on HDI metrics. For instance, the life expectancy at birth (one of the sub-metrics of HDI) in India has gone from around 40 years in 1947 to around 70 years now.

- India has also taken giant strides in education enrolment at all three levels — primary, secondary, and tertiary.

What is the distance left to cover?

- When compared to the developed countries or China, India has a fair distance to cover.

- Even though India is the world’s third-largest economy in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, most Indians are still relatively poor compared to people in other middle income or rich countries.

- Ten per cent of Indians, at most, have consumption levels above the commonly used threshold of $10 (PPP) per day expenditures for the global middle class.

How much can India achieve by 2047?

- One way to make this assessment is to look at how long other countries took to get there.

- For instance, in per capita income terms, Norway was at India’s current level 56 years ago — in the year 1966.

- China reached that mark in 2007. Theoretically then, if India were to grow as fast as China did between 2007 and 2022, then, broadly speaking, it will take India another 15 years to be where China is now.

- India’s current HDI score (0.64) is much lower than what any of the developed countries had even in 1980. China reached the 0.64 level in 2004, and took another 13 year to reach the 0.75 level — that, incidentally, is the level at which the UK was in 1980.

- The World Bank’s 2018 report had made a mention of what India could achieve by 2047.

- “By 2047 — the centenary of its independence — at least half its citizens could join the ranks of the global middle class. By most definitions this will mean that households have access to better education and health care, clean water, improved sanitation, reliable electricity, a safe environment, affordable housing, and enough discretionary income to spend on leisure pursuits” .

- But it also laid out a precondition for this to happen: “Fulfilling these aspirations requires income well above the extreme poverty line, as well as vastly improved public service delivery.”

Source: Indian Express