Science and Technology

In news: ESIWA and ORF convened the first high-level, closed-door roundtable in New Delhi on the side-lines of the Raisina Dialogue 2022 to discuss and examine European and Indian positions on cybersecurity issues.

- The event was the first in a series of six roundtables that ESIWA and ORF will host in 2022-23 in order to advance track 1.5 cyber-dialogues between the EU and India.

- The objective is to determine how can EU and India cooperate bilaterally and multilaterally to increase adherence to cyber norms and implementation of cyber confidence-building measures, involvement of private sector stakeholders and addressing organised forms of cybercrime such as ransomware.

- The conclusions of the roundtable discussions will be put forward for consideration during the formal EU–India Cybersecurity Dialogue meetings.

- It addressed the theme, ‘Enhancing Global Cybersecurity Cooperation: European and Indian Perspectives’.

Context:

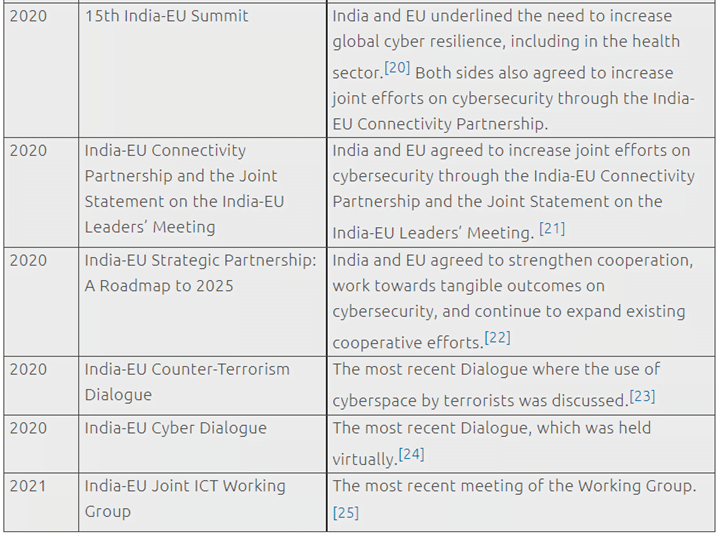

- The European Union (EU) and India have cooperated on cybersecurity since the early 2000s on lines of common values of democracy and rule of law and the need to protect the rules-based order.

- For both India and the EU, the imperative is to promote an open, free, secure, and accessible cyberspace that enables growth and innovation.

- Most recently, in April 2022, the two sides established the EU-India Trade and Tech Council to tackle challenges at the nexus of trade, trusted technology and security

The Challenges:

- The last few years have seen a sharp rise in the incidence of cyber-attacks in various parts of the world, partly as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak that forced a shift to digitisation of economic, social and other activities.

- Cybersecurity firm McAfee estimated that as of December 2020, incidents of cybercrime had cost the world economy over US$ 1 trillion, up by 150 percent from a 2018 estimate of US$ 600 billion.

- In 2021, India experienced the third highest number of data breaches in the world, with over 86.3 million breaches occurring in the first 11 months of the year.

- Similarly, the Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment 2021 found that the EU was witnessing a spike in ransomware affiliate programmes, mobile malware, and online fraud.

- The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) reported 304 malicious attacks against critical sectors in 2020, double the number from the previous year.

- In India, the National Crime Records Bureau recorded a rise of 11.8 percent in cybercrime in 2020; and over 1.15 million incidents of cyber-attacks were reported to the country’s Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In) in the same year.

- In 2021, the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center and the Digital Security Unit observed that most nation state actors focused operations and attacks on government agencies, intergovernmental organisations, nongovernmental organisations, and think tanks for traditional espionage or surveillance objectives.

- During 2019–21, Microsoft delivered over 20,500 Nation State Notifications (NSNs) when customers were targeted or compromised by nation state activities.

- The instances of cybercrime in India have increased fivefold between 2018 and 2021.

International Mechanisms:

- The Budapest Convention: The Council of Europe’s Convention on Cybercrime, also known as the Budapest Convention came into force in 2004 as the first international instrument on cybercrime.

- It is currently the only binding international instrument on cybercrime

- The Convention deals with offences such as computer-related fraud, illegal access, misuse of devices, and child pornography.

- Its principal aims are to: (1) Harmonise domestic laws on cybercrime; (2) Support the investigation and prosecution of cybercrimes; and (3) Facilitate international cooperation on cybercrime. Since 2006, the first Additional Protocol to the Convention that criminalises ‘acts of a racist and xenophobic nature committed through computer systems’ has been in effect.

- The UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE): Established in 2004 by UNGA to explore the impact of developments in ICT on international peace and security.

- The mandate of the GGEs has been to examine threats in cyberspace along with possible cooperative measures, and to maintain an open, secure, peaceful and accessible ICT environment.

- EU itself is not a member of the GGEs, many individual EU member states have held expert positions on past GGEs.

- India was an active member of the fifth (2016-17) and sixth (2019-21) GGEs.

- While it was not a member of the third GGE for 2014–15, it responded to the Group’s deliberations by initiating a national study for examining the norms for cooperation.

- The UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG): Established in 2019 by UNGA to provide a “democratic, transparent and inclusive platform”.

- The OEWG’s mandate is to develop rules, norms and principles of responsible behaviour of States; devise ways to implement these rules; identify CBMs and capacity-building measures; and study cyber threats and the application of international law to cyberspace.

- India actively participated in the first OEWG and contributed substantively towards its final report.

- India stated that a “common understanding on how international law is applicable to State’s use of ICTs is important for promoting an open, secure, stable, accessible, interoperable and peaceful ICT environment.

- The Proposed Programme of Action (PoA): Established in 2020 by over 40 countries (including EU member states) for advancing responsible state behaviour in cyberspace.

- To end the dual-track discussions of the GGE and OEWG, and to establish a permanent UN forum to consider the use of ICTs by states in the context of international security.

- It is envisaged as a single, long-term, inclusive and progress-oriented platforms.

- India has been participating in UN-mandated cyber processes and consultations.

Recommendations:

- Build upon and expand EU-India cyber interactions – by exchanging best practices and lessons learned on the implementation of cyber norms and engage in discussions on the drafting and implementation of relevant international standards for new technologies such as 5G; and undertake joint efforts to advance global cyber resilience.

- Promote multistakeholder engagement at various levels by building public-private consensus and partnerships and foster a more inclusive ecosystem for cyber cooperation.

- Jointly undertake capacity building exercises and confidence-building measures, particularly in areas such as promoting cybersecurity, strengthening encryption standards, and developing the capacity of cyber professionals.

- Support to third countries could also be strategic, focusing on issues such as helping eradicate the safe havens for cybercriminals operating out of these countries; or facilitating cooperation among third countries from an enforcement perspective.

- Explore the implications and possible benefits of the Programme of Action (PoA).

- Work towards crafting new standards for data governance and data sharing.

- Work towards developing global standards in selected domains.

- Continue to build trust through increased cooperation.

Way forward:

- The present ESIWA-ORF project will complement the official EU-India interactions on cybersecurity.

- These could include

- defending against data breaches and cyber-attacks

- using emerging technologies to fight cybercrime

- exploring measures that states could take to ensure a balance between cybersecurity and free speech

- deliberating upon the ongoing process of drafting a comprehensive UN cybercrime treaty

- As recommended, a multistakeholder approach involving governments, civil society organisations, and the private sector will be adopted across efforts to enhance cybersecurity cooperation.

Source: ORF Online