Agriculture

Context:

- A new draft policy by Delhi-based research non-profit People’s Resource Centre, says some 60 per cent of Delhi’s demand for meat is fulfilled by city-grown produce, as is 25 per cent of its milk and 15 per cent of its vegetable needs.

- Yet policies on land use and farming in the National Capital do not acknowledge the role of cultivation and distribution of food in urban areas

- India is rapidly urbanising and is estimated to host 50 per cent of its population in cities by 2050. Hence, there needs to be increased focus on urban farming

The “Draft Citizen’s Policy for Urban Agriculture in Delhi”

- It was submitted to the Delhi government in 2022

- It aims to provide a holistic framework for urban farming.

- It recommends building on existing practices, promoting residential and community farming through rooftop and kitchen gardens, allocating vacant land for agricultural use, creating a market, developing policies for animal rearing and spreading awareness.

- These recommendations are crucial to ensure food security for urban communities.

Urban agriculture

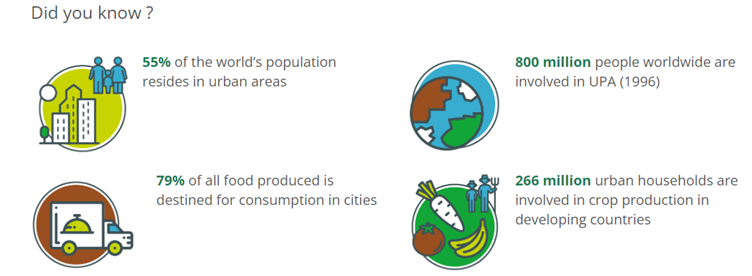

- Urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA) can be defined as practices that yield food and other outputs through agricultural production and related processes (transformation, distribution, marketing, recycling) taking place on land and other spaces within cities and surrounding regions.

- It involves urban and peri-urban actors, communities, methods, places, policies, institutions, systems, ecologies and economies, largely using and regenerating local resources to meet changing needs of local populations while serving multiple goals and functions.

Need and Significance

- Rapid urbanisation, population explosion and climate change increases the risk of food shortage – A 2017 study published in the International Journal on Emerging Technologies.

- 50 per cent of women and children in urban areas are anaemic due to lack of adequate nutrition – 2010 report by M S Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai. Both studies recommend urban agriculture

- Globally, in 2020, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization acknowledged that urban and peri urban farming can contribute to local food and nutritional needs, enable jobs and reduce poverty.

- Our cities already suffer from high population density, unaffordable housing, improper waste disposal, water scarcity most of the year and flooding during the rains, pollution and attendant illnesses, food and nutritional insecurity and urban poverty, among others.

Indian scenario

- Noting the critical need for a paradigm shift in urban planning, 2022-23 budget speech announced the decision to set up a high-level committee to steer the required changes in urban policy, planning, capacity building and governance.

- Given the current context and future exigencies, this presents an opportune moment to critically engage with urban land-use planning (ULP), especially urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA), as one of the essential elements of sustainable urbanisation.

- In 2008, Pune’s civic administration launched a city farming project to train and encourage people to take up farming on allocated land.

- Kerela had been food dependent until 2012 when the state government launched a vegetable development programme to encourage gardening in houses, schools, government, and private institutions.

- According to Kerala State Planning Board, vegetable production rose from 825,000 tonnes in 2011-12 to 1.3 million tonnes in 2014-15.

- Similarly, in 2014, the Tamil Nadu government introduced a “do-it-yourself” kit for city dwellers to grow vegetables on rooftops, houses and apartment buildings under its Urban Horticulture Development Scheme.

- Since 2021, Bihar encourages terrace gardening in five smart cities through subsidy for input cost.

Challenges

- Absence in Planning – Agriculture, mostly associated with rural practice, hardly finds a place in urban planning guidelines. For instance, India’s Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulations and Implementation (URDPFI) guidelines mention agriculture while preparing city plan

- Policy lacunae – The recently released draft Master Plan of Delhi for 2041, does not acknowledge the role of the practice. It aims to divide 8,000 hectares of land along the Yamuna into two sub-zones and restrict human activity or settlement in areas directly adjacent to the river.

- Rapid development is a hindrance.

- Citing the example of Jaunti village in Delhi, where the Green Revolution began – It has become an ‘urban village’, making its land non-agricultural.

- Farmers cannot avail benefits under any agricultural schemes such as crop insurance.

- Environmental degradation – Excessive use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides in urban farms can lower produce and soil quality.

- Scalability – Kitchen gardening or small-scale community farming cannot sustain the large population, but can act as a cushion to protect urban residents from inflation, vulnerabilities of weather or crises such as COVID-19

Suggestion for future

- Integration is key – While such initiatives are welcome, their impact cannot be expected to be widespread without a strong policy for urban farming. For instance, Pune’s 2008 initiative failed to take off due to poor interest from people and the government.

- Viability of urban agriculture.

- Farming in cramped urban spaces marred by water scarcity and pollution is not easy.

- A 2016 paper titled Future of Urban Agriculture in India by the Hyderabad-based Institute for Resource Analysis and Policy mentions that in Delhi, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad and Chennai, wastewater is directly or indirectly used for urban farming.

- Hydroponics, a method of soilless farming that uses nutrient solutions to sustain plants, offers a cleaner approach.

- Compared to commercial farming, hydroponics requires 90 per cent lesser water, which can be reused. One can grow more plants in the space given,” she says. However, she admits that markets for such initiatives are still niche and at a nascent stage.

- Prioritise estimation of waste management capacity, build infrastructure for it and regulate industrial installations to this capacity.

- Adequate political will for financial inputs and enforcement of regulations will be essential for often fund-starved urban administrations and for curbing violations of environmental norms.

- International best practises

- As per World Economic Forum informs that Singapore is already producing almost 10 per cent of its food through rooftop farming while conventional farming is done only on 1 per cent of its land.

- Public spaces are landscaped to grow vegetables and fruits in raised beds, containers or vertical frames. These, besides generating income, also extend positive externalities to the neighbourhood through clean and green environment, nutrition and cultural connect

- To promote urban farming, governments must recognise informal practices and link them with agricultural schemes.

Way forward;

- It is an appropriate time to introspect and transform the way we produce and consume.

- With climate change, there is a greater need for localising nourishment of humans to prevent starvation and overcome nutritional deficiency

- Apart from governments, citizens and professionals from the field of architecture, planning, agriculture, social sciences and private developers need to cross-learn and co-create productive green urbanism for a resilient future.

Source: DTE