IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis

Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

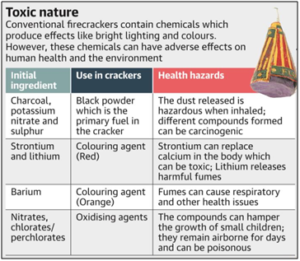

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

- Ahead of Deepavali, the Supreme Court relaxed the blanket ban on fireworks in Delhi and the National Capital Region (NCR) and allowed the sale of green fireworks approved by Petroleum and Explosives Safety Organisation (PESO).

About Green Crackers:

- Nature: Green crackers are dubbed as ‘eco-friendly’ crackers and are known to cause less air and noise pollution as compared to traditional firecrackers.

- Designed by: These crackers were first designed by the National Environmental and Engineering Research Institute (NEERI), under the aegis of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in 2018.

- Objective: These crackers replace certain hazardous agents in traditional crackers with less polluting substances with the aim to reduce the noise intensity and emissions.

- Range of sound: Regular crackers also produce 160-200 decibels of sound, while that from green crackers are limited to about 100-130 decibels.

- Features:

- Most green crackers do not contain barium nitrate, which is the most dangerous ingredient in conventional crackers.

- Green crackers use alternative chemicals such as potassium nitrate and aluminium instead of magnesium and barium as well as carbon instead of arsenic and other harmful pollutants.

- Types of green crackers:

- SWAS – Safe Water Releaser: These crackers do not use sulphur or potassium nitrate, and thus release water vapour instead of certain key pollutants. It also deploys the use of diluents, and thus is able to control particulate matter (PM) emissions by upto 30%.

- STAR – Safe Thermite Cracker: Just like SWAS, STAR also does not contain sulphur and potassium nitrate, and besides controlling particulate dust emissions, it also has lower sound intensity.

- SAFAL – Safe Minimal Aluminium: It replaces aluminium content with magnesium and thus produces reduced levels of pollutants.

- Production: All three types of green crackers can currently only be produced by licensed manufacturers, approved by the CSIR.

- Certification: The Petroleum and Explosives Safety Organisation (PESO) is tasked with certifying that the crackers are made without arsenic, mercury, and barium, and are not loud beyond a certain threshold.

About Petroleum and Explosives Safety Organisation (PESO):

- Ministry: PESO is an office under the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce and Industries.

- Establishment: It was established in 1898 as a nodal agency for regulating safety of substances such as explosives, compressed gases and petroleum.

- Head office: Its head office is located in Nagpur, Maharashtra.

Source:

Category: International Relations

Context:

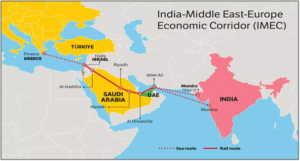

- The IMEC visualises the upgradation of maritime connectivity between India and the Arabian Peninsula, as well as high-speed trains running from the ports in the UAE to the Haifa port in Israel through Saudi Arabia and Jordan.

About India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC):

- Launch: The IMEC is a strategic multi-modal connectivity initiative launched through a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) during the G20 Summit 2023 in New Delhi.

- Members: Signatories include India, US, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, France, Germany, Italy and the European Union.

- Objective: It aims to develop an integrated network of ports, railways, roads, sea lines, energy pipelines, and digital infrastructure aimed at enhancing trade between India, the Middle East, and Europe.

- Alternative to BRI: IMEC seeks to position itself as a viable alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by promoting transparent, sustainable, and debt-free infrastructure without compromising national sovereignty.

- Part of PGII: The initiative is a part of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), launched by the G7 in 2021.

- Focus on cooperation: IMEC includes energy pipelines, clean energy infrastructure, and undersea cables to enhance trade and energy cooperation.

- Corridors: IMEC has two parts the Eastern Corridor (India to Gulf) and the Northern Corridor (Gulf to Europe).

- Significance for India:

- IMEC is set to reduce logistics costs by up to 30% and transportation time by 40%, compared to the Suez Canal Maritime route making Indian exports more competitive globally.

- In sync with OSOWOG: India’s One Sun One World One Grid (OSOWOG) initiative aligns with IMEC’s energy goals, enabling India to harness solar and green hydrogen power from the Middle East, a region rich in renewable energy potential.

- It will attract Foreign Direct Investment into India, particularly in infrastructure, logistics, green energy, and digital technologies, helping India access low-cost renewable energy and transition to a low-carbon economy.

- Setback: The project faced a major setback due to the Israel-Hamas conflict in 2023. Geopolitical instability in the Middle East has temporarily slowed momentum.

Source:

Category: Polity and Governance

Context:

- The Delhi High Court sought a response from the Union government on long-pending vacancies in the National Commission for Minorities (NCM).

About National Commission for Minorities (NCM):

- Genesis: The Minorities Commission (MC) was established in 1978 through a Ministry of Home Affairs Resolution and was moved to the newly created Ministry of Welfare in 1984.

- Nature: It is a statutory body established under the National Commission for Minorities Act, 1992. The first statutory Commission was constituted on 17th May 1993. In 1988, the Ministry of Welfare excluded linguistic minorities from the Commission’s jurisdiction.

- Objective: It was formed with the vision to safeguard and protect the interests of minority communities.

- Composition: It consists of a Chairperson, a Vice-Chairperson, and five Members, all nominated by the Central Government but absence of a full body has led to concerns over inefficiency.

- Eligibility of members: Each member must belong to one of the six notified minority communities: Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist, Parsi, and Jain.

- Powers: It has quasi-judicial powers and each member serves a three-year term from the date they assume office.

- Removal: The Central Government may remove the Chairperson or any Member of the NCM if they:

- Are adjudged insolvent,

- Take up paid employment outside their duties,

- Refuse or become incapable of acting,

- Are declared of unsound mind by a court,

- Abuse their office, or

- Are convicted of an offence involving moral turpitude.

About Minorities in India:

- Not defined by Constitution: The Constitution of India does not provide a definition for the term ‘Minority’, but the Constitution recognises religious and linguistic minorities. The NCM Act, 1992 defines a minority as “a community notified as such by the Central government.

- List of Minority Communities: As per a 1993 notification by the Ministry of Welfare, the Government of India initially recognized five religious communities—Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Zoroastrians (Parsis) as minority communities. Later, in 2014, Jains were also notified as a minority community.

Source:

Category: Miscellaneous

Context:

- In a changing global mobility landscape, both India and the United States have seen notable drops in their passport power, according to the 2025 Henley Passport Index, which ranks the world’s most travel-friendly passports.

About Henley Passport Index:

- Nature: The Henley Passport Index ranks global passports based on the number of destinations their holders can travel to without a visa, with data sourced from the International Air Transport Association (IATA).

- Definition of a powerful passport: It is defined by travel openness, the freedom to enter more countries without having to deal with visa applications, long processing times, or bureaucratic hurdles.

- Published by: It is compiled and published by Henley & Partners, a global citizenship and residence advisory firm.

- Findings from Henley Passport Index 2025:

- Leading the rankings in 2025 are three Asian countries: Singapore holds the top spot with access to 193 destinations visa-free, followed by South Korea with 190 destinations and Japan with 189 destinations.

- India’s passport has fallen to 85th place, offering visa-free access to 57 countries, down from 59 in 2024. This marks a further decline from the 77th position earlier this year, underscoring a steady reduction as per the index.

- For the first time in the Index’s 20-year history, the United States has dropped out of the global top 10. The US passport now ranks 12th, tied with South East Asian Malaysia, offering visa-free access to 180 destinations out of 227.

Source:

Category: International Relations

Context:

- China has filed a complaint against India in the World Trade Organization (WTO) over New Delhi’s subsidies for electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries.

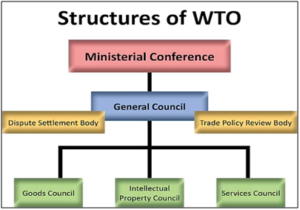

About World Trade Organization (WTO):

- Formation: WTO was formed under the Marrakesh Agreement signed on 15th April 1994 by 123 countries after the Uruguay Round negotiations (1986-94) of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), leading to the birth of WTO in 1995.

- Objective: It is an international institution formed to regulate the rules for global trade among nations.

- Successor: WTO succeeded the GATT which had regulated world trade since 1948. GATT focused on trade in goods, while WTO covers trade in goods, services, and intellectual property, including creations, designs, and inventions.

- Headquarters: Its headquarters is located in Geneva, Switzerland.

- Members: It has 166 countries, representing 98% of global trade.

- Governing bodies:

- Ministerial Conference (MC): It is the highest decision-making authority.

- Dispute Settlement Body (DSB): It resolves trade disputes.

- Major WTO Agreements:

- TRIMS (Trade-Related Investment Measures): It prohibits measures that discriminate against foreign products, e.g., local content requirements.

- TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights): It resolves disputes over intellectual property rights.

- AoA (Agreement on Agriculture): It promotes agricultural trade liberalization, focusing on market access and domestic support.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(UPSC GS-II — Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation)

Context (Introduction)

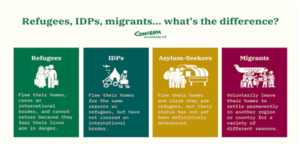

India hosts diverse refugee populations but has no single refugee law. Recent consolidation under the Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 streamlines foreigner management, yet status-blind enforcement and religion-linked pathways risk arbitrariness, rights gaps, and security-humanitarian trade-offs.

Main Arguments

- No treaty or national law on refugees: India is not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention/1967 Protocol and lacks a comprehensive domestic refugee statute, pushing decisions into ad-hoc executive discretion.

- New framework is status-blind: The Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 repeals four laws and tightens registration/penalties but does not codify who is a “refugee,” leaving genuine asylum-seekers vulnerable to “illegal migrant” labelling.

- Uneven, group-specific handling: Tibetans received a rehabilitation policy; by contrast, Sri Lankan Tamils long lacked equivalent relief—until a September 2025 notification exempted pre-2015 arrivals from prosecution for document lapses, still short of durable status.

- CAA’s selective inclusion: The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 expedites naturalisation for specified non-Muslim minorities from three countries, drawing criticism for excluding Rohingya and Sri Lankan Tamils, undermining neutrality.

- Operational pressures on states: Border-states face large arrivals (e.g., biometric drives in Mizoram for Myanmar-origin arrivals) alongside MHA crackdowns on fraudulent documents—intensifying the need for fair, standardised screening.

Criticisms / Drawbacks

- Arbitrariness risk: Without legal refugee criteria, the “refugee vs. infiltrator” line depends on executive assessment, enabling politicisation and inconsistent treatment across groups and states.

- Rights vacuum: Absence of codified rights (work, health, education) leaves refugees reliant on uneven local practice; UNHCR counted ~2.11 lakh “persons of concern” (Mar 2023) and >240,000 by end-2024 needing predictable protections.

- Religion-linked pathways: CAA’s design invites Article-14 critiques and undermines India’s historic secular humanitarian stance, say multiple rights analyses.

- Judicial ambivalence on non-refoulement: Some High Courts read non-refoulement into Article 21; the Supreme Court, however, has declined to stay Rohingya deportations and emphasised that the right to reside belongs to citizens.

- Security-only drift: Enforcement drives, document cancellations and penalties address risks but—without a protection track—can sweep up bona fide refugees, heightening vulnerability.

Reforms to Pursue

- Enact a National Refugee Protection Act: Define “refugee” in line with global standards; incorporate screening, registration, appeal, and periodic review; embed due-process and non-refoulement safeguards consistent with Article 21 jurisprudence.

- Create a Refugee Status Determination (RSD) system: A specialised, independent authority (with UNHCR technical support) to conduct case-by-case RSD; interoperable with the new immigration database while firewalling protection data.

- Adopt religion-neutral admission & relief: Calibrate pathways (long-term visas, work permits, community sponsorship) by risk and vulnerability, not identity; regularise legacy caseloads (e.g., Sri Lankan Tamils, Afghans, Myanmar nationals) through uniform criteria.

- Rights guarantees with guardrails: Minimum standards for education, primary healthcare, and lawful work to reduce precarity and improve compliance—paired with security vetting and biometrics already being rolled out in border states.

- Regional & multilevel coordination: Institutionalise Centre-State-UNHCR coordination cells; pursue a SAARC/BIMSTEC compact on disaster/conflict displacement to share data, returns, and assistance frameworks.

Conclusion

India’s civilisational ethic and strategic interests converge on one point: clarity. A religion-neutral refugee law, welded to rigorous screening and clear rights-duties, would replace ad-hocism with predictable protection—strengthening security, federal coordination, and India’s credibility as a humane regional leader.

Mains Question

- Critically examine the need for a comprehensive legal and institutional framework to manage refugees in a fair and consistent manner. (15 marks, 250 words)

Source: The Hindu

(Relevance: UPSC GS Paper III – Infrastructure: Energy; Effects of Liberalization on the Economy; Growth of Technology and Industrial Development)

Context (Introduction)

India’s path to 500 GW renewable energy by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2070 hinges on securing critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements (REEs) — essential for clean technology, battery storage, and green industrial growth.

Importance of Critical Minerals

- Green Technology Backbone: Critical minerals power the core of clean-tech systems — lithium and cobalt for EV batteries, REEs such as neodymium and dysprosium for wind turbines and motors, and graphite for battery anodes.

- Economic Driver: India’s EV market is projected to reach ₹1.8 lakh crore by 2030, growing at 49% CAGR (NITI Aayog, 2023). The battery storage market, valued at $2.8 billion in 2023, is expected to grow fivefold by 2030.

- Strategic Necessity: As fossil fuels lose relevance, critical minerals will define energy security. India’s dependence on imports for lithium (100%), cobalt (100%), and REEs (90%) poses risks similar to the 20th-century oil dependence.

- Climate Commitments: These minerals are indispensable for India’s Energy Transition Roadmap and National Hydrogen Mission — both critical to meeting Paris Agreement goals.

Main Arguments

(a) Import Dependence and Global Concentration

- India’s critical mineral imports may cross $20 billion by 2030 (NITI Aayog).

- China controls 60% of REE mining and 85% of processing, while Indonesia refines 40% of nickel, posing major supply risks.

- China’s 2023 export curbs on gallium and germanium exposed the fragility of global dependence.

(b) Domestic Exploration and Emerging Potential

- GSI discovered 5.9 million tonnes of lithiuminReasi, J&K — India’s first major deposit.

- Auctions in Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh cover lithium, graphite, and REEs.

- The MMDR Act 2023 opened 20 critical minerals for private exploration, boosting FDI potential.

(c) Institutional and Strategic Efforts

- National Critical Mineral Mission (₹34,300 crore) targets exploration, mining, and recycling.

- KABIL acquiring lithium assets in Argentina and Australia; IREL and NMDC expanding REE extraction.

- India–Australia and India–U.S. partnerships foster technology sharing and diversified sourcing.

(d) Recycling and Urban Mining

- India produces 3.9 million tonnes of e-waste yearly; only 10% recycled (CPCB 2022).

- Battery Waste Rules 2022 aim for 70% recycling by 2030.

- Attero Recycling and Lohum Cleantech lead e-waste recovery, potentially meeting 15–20% of mineral demand (TERI 2023).

(e) Global Partnerships and Mineral Diplomacy

- Under the Quad and IPEF, India collaborates with Australia, Japan, and the U.S. for resilient supply chains.

- The India–Australia Critical Minerals Partnership (2023) committed $150 million for joint projects.

- India joined the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) to secure lithium, cobalt, and REEs through multilateral cooperation.

Key Issues and Challenges

- Low Value-Addition: India contributes less than 1% of global REE output and lacks refining technology, forcing export of raw ores.

- Institutional Overlaps: Multiple ministries (Mines, MNRE, MEITY, Commerce) lead to fragmented execution.

- Private Sector Reluctance: Long gestation, high exploration costs, and regulatory delays deter private investment.

- Environmental Sensitivity: Mining lithium and REEs consumes significant water and impacts biodiversity; ESG compliance remains weak.

- Technology Gaps: Dependence on imported processing and separation technologies limits domestic innovation capacity.

Reforms and Measures Needed

- Operationalise NCMM Effectively: Define time-bound exploration targets, use AI-based geological surveys, and link outcomes to production incentives.

- Build Processing and Refining Hubs: Establish National REE and Battery Metal Refineries under PPPs in mineral-rich states.

- Strategic Stockpiling: Create a National Critical Mineral Reserve similar to the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

- Promote Recycling Ecosystem: Incentivise urban mining start-ups via tax rebates and integrate e-waste collection under Swachh Bharat 2.0.

- Global Joint Ventures: Expand KABIL’s footprint in Latin America and Africa through concessional credit lines and EXIM Bank support.

- Invest in R&D: Strengthen collaboration among IITs, CSIR-NML, and ARCI for mineral substitution, eco-friendly extraction, and advanced battery chemistries.

Conclusion

Critical minerals are the new strategic resource frontier. India must transition from being a raw importer to a value-chain participant through robust domestic mining, technology partnerships, and circular-economy innovation. A coherent, fact-driven mineral policy backed by science, sustainability, and diplomacy will transform India into a critical-mineral power and a leader in green growth.

Mains Question:

- Securing access to critical minerals is vital for India’s clean energy transition. Examine the major bottlenecks in developing a domestic critical mineral ecosystem and suggest policy measures to overcome them. (15 marks, 250 words)

Source: The Hindu

(Relevance: UPSC GS Paper II – Structure, Organization and Functioning of the Judiciary; Role of Women and Issues Related to Gender Equality)

Context (Introduction)

Despite progress in the lower judiciary, where women constitute nearly 38% of judges, India’s higher judiciary remains male-dominated — with only 3.1% women in the Supreme Court and 14% in High Courts, reflecting deep systemic imbalance.

Main Arguments

- Stark Gender Disparity in Higher Judiciary: As per the India Justice Report 2025, only one woman serves among the 34 judges of the Supreme Court, and only one woman Chief Justice heads a High Court. This absence of diversity diminishes representativeness in justice delivery and undermines the constitutional promise of equality.

- Collegium System as a Structural Barrier: The current Collegium system—an insular network of senior judges—has limited transparency and inclusiveness. Women and marginalized groups outside elite legal circles often lack access to nomination networks, perpetuating male dominance in appointments.

- Lower Judiciary as a Model of Inclusion: Women account for 38% of judges in the subordinate courts due to competitive recruitment exams, which ensure merit-based entry without informal bias. However, a 2023 Supreme Court report noted that nearly 20% of district courts lack separate toilets for women, indicating the need for gender-sensitive infrastructure and promotions to sustain participation.

- Proposal for All-India Judicial Service (AIJS): Supported by President Droupadi Murmu (2023), AIJS seeks merit-based and transparent national recruitment, akin to the UPSC Civil Services Exam, under Article 312 of the Constitution. It would open doors for women and underrepresented groups through uniform exams, training, and service conditions.

- UPSC as an Effective Model: The UPSC Civil Services Exam 2024 demonstrated inclusive outcomes: of 1,009 selected candidates, 47% were from reserved categories and 11 of the top 25 were women. Similarly, 28% of IPS recruits in 2024 were women — showing that national-level competitive systems can ensure diversity without compromising merit.

Issues and Bottlenecks

- Opaque Collegium Practices: No published selection criteria or diversity data (as flagged by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Law and Justice, 2022).

- Promotion Barriers: Only 13% of women district judges were promoted to High Courts in the last decade (Department of Justice data, 2023).

- Institutional Bias: Studies by the Bar Council of India (2022) show implicit bias in senior appointments, where women advocates are less likely to be recommended.

- Workplace Constraints: The Centre for Research and Planning (SC, 2023) reported inadequate crèches, washrooms, and safety measures in 18–20% of court complexes.

- Cultural Stereotypes: The Oxford Policy Management Study (2021) found women lawyers face informal exclusion from chambers, mentorship, and high-value litigation, restricting professional visibility.

Reforms and Policy Measures

- Operationalise the All-India Judicial Service: Adopt a transparent, merit-based system under UPSC, ensuring inclusivity across gender and social groups (supported by Law Commission Report 214 and NITI Aayog’s Strategy for New India @75).

- Diversify the Collegium Process: Publish annual gender and diversity reports; include eminent jurists or retired women judges as advisors to the Collegium (Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy (2023)

- Institutional Infrastructure Upgrade: Implement gender-friendly standards across court complexes through Centrally Sponsored Scheme for Judicial Infrastructure (2021–26) with earmarked gender budgets.

- Career Progression and Mentorship: The National Judicial Academy can run leadership and mentorship programmes for women district judges to prepare them for higher roles.

- Data Transparency and Accountability: Annual Judicial Diversity Index by the Department of Justice and publication on the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) to monitor gender equity trends.

Conclusion

Gender equity in the judiciary is not symbolic — it is central to justice, equality, and institutional legitimacy. Reforming judicial appointments through AIJS and transparent Collegium practices can democratize access, enhance trust, and reflect India’s constitutional morality. True equality in courts will mark India’s transition from formal justice to substantive equality under law.

Mains Question:

- Women continue to be severely underrepresented in India’s higher judiciary. Examine the causes of this imbalance and suggest reforms to make the judiciary more inclusive and representative. (15 marks, 250 words)

Source : The Hindu