IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis

Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: International Relations

Context:

- The ongoing Financial Action Task Force (FATF) meetings in Paris are expected to deliberate on state sponsorship as a means to fund and support terrorism, including the financing of banned outfits and their proxies operating in Pakistan.

About Financial Action Task Force (FATF):

- Establishment: FATF is the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog set up in 1989 out of a G-7 meeting of developed nations in Paris.

- Objective: Initially, its objective was to examine and develop measures to combat money laundering. After the 9/11 attacks on the US, the FATF in 2001 expanded its mandate to incorporate efforts to combat terrorist financing.

- Members: It is a 39-member body representing most major financial centres in all parts of the globe. Out of 39 members, there are two regional organisations: the European Commission, and the Gulf Cooperation Council.

- India and FATF: India joined with ‘observer’ status in 2006 and became a full member of FATF in 2010. India is also a member of its regional partners, the Asia Pacific Group (APG) and the Eurasian Group (EAG).

- Special Recommendations: In April 1990, the FATF issued a report containing a set of Forty Recommendations intended to provide a comprehensive plan of action needed to fight against money laundering. In 2004, the FATF published a Ninth Special Recommendations, further strengthening the agreed international standards for combating money laundering and terrorist financing – the 40+9 Recommendations.

- Structure: The FATF Plenary is the decision-making body of the FATF. It meets three times per year.

- Secretariat: The FATF Secretariat is located at the OECD headquarters in Paris. The Secretariat supports the substantive work of the FATF membership and global network.

- Funding: The funding for the FATF Secretariat and other services is provided by the FATF annual budget to which members contribute.

- Grey and Black Lists of the FATF:

- Grey List: The Grey List includes countries that are considered safe haven for supporting terror funding and money laundering. It serves as a warning that the country may enter the blacklist.

- Black List: The Black List includes Non-Cooperative Countries or Territories (NCCTs) that support terror funding and money laundering activities.

- Implications of inclusion in FATF Lists:

- Economic sanctions from financial institutions affiliated with FATF (IMF, World Bank, ADB etc.)

- Problem in getting loans from such financial institutions and countries

- Reductions in international trade

- International boycott

Source:

Category: Polity and Governance

Context:

- The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) issued notice to the Kerala, Tripura, and Manipur governments over the alleged attack on three journalists at different places in the States in the past three months.

About National Human Rights Commission (NHRC):

- Establishment: NHRC was established on 12th October 1993, under the Protection of Human Rights Act (PHRA), 1993.

- Amendments: It was amended by the Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Act, 2006, and Human Rights (Amendment) Act, 2019.

- Objective: It ensures the protection of rights related to life, liberty, equality, and dignity of individuals. It also ensures the rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution and international covenants enforceable by Indian courts.

- In sync with Paris principles: It was established in conformity with the Paris Principles, adopted for promoting and protecting human rights.

- Composition: The NHRC consists of a chairperson, five full-time Members and seven deemed Members. The chairman is a former Chief Justice of India or a Supreme Court judge.

- Appointment of members: The chairman and members appointed by the President on the recommendations of a six-member committee. The committee consists of the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, the Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha, leaders of the Opposition in both Houses of Parliament, and the Union Home Minister.

- Tenure of members: The chairman and members hold office for a term of three years or until they reach the age of 70.

- Major functions:

- It possesses powers of a civil court with judicial proceedings.

- It is empowered to utilise the services of central or state government officers or investigation agencies for investigating human rights violations.

- It can investigate matters within one year of their occurrence.

- Not binding: Its recommendations are primarily advisory in nature.

Source:

Category: History and Culture

Context:

- Manipur government holds fish fair ahead of the Ningol Chakouba festival and targets to sell 1.5 lakh kg of various fish varieties.

About Ningol Chakouba Festival:

- Annual festival of Manipur: The festival is held every year in Manipur on the second day of the lunar month of Hiyangei of the Meitei calendar.

- Primarily celebrated by Meiteis: The festival is mainly celebrated by the Meiteis but nowadays many other communities also have started to celebrate it.

- Objective: It emphasises the importance of happiness and reunion of a family in bringing peace and harmony in a society.

- Nomenclature: Ningol means ‘married woman’ and Chakouba means ‘invitation for feast’; so the festival is the one where the married women are invited to their parents’ home for a feast.

- Uniqueness: The main component of the festival is the visit of married sisters to their maternal homes for grand feast and joyous reunion followed by giving away the gifts.

About the Meitei Community:

- Separate ethnic group: They are the predominant ethnic group of Manipur State.

- Language: They speak the Meitei language (officially called Manipuri), one of the 22 official languages of India and the sole official language of Manipur State.

- Distribution: The Meiteis primarily settled in the Imphal Valley region in modern-day Manipur, though a sizable population has settled in the other Indian states of Assam, Tripura, Nagaland, Meghalaya, and Mizoram. There is also a notable presence of Meitei in the neighbouring countries of Myanmar and Bangladesh.

- Clans: They are divided into clans, the members of which do not intermarry.

- Economy: Rice cultivation on irrigated fields is the basis of their economy.

Source:

Category: Government Schemes

Context:

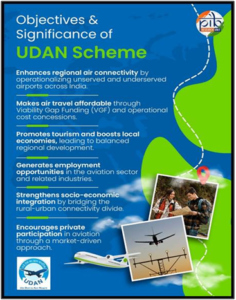

- Ministry of Civil Aviation is celebrating the 9th anniversary of the Regional Connectivity Scheme – UDAN (Ude Desh Ka Aam Nagrik). It was held in New Delhi, chaired by Secretary (Civil Aviation) and other senior officers of the Ministry.

About UDAN (Ude Desh Ka Aam Nagrik) Scheme:

- Launch: The scheme was designed under the National Civil Aviation Policy (NCAP) 2016, with a focus on connecting Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities through a market-driven yet financially supported model.

- Objective: UDAN aims to democratize aviation and enhance regional connectivity, ensuring that even remote regions of the country are accessible by air.

- Nodal Ministry: It works under the Ministry of Civil Aviation.

- Implementing authority: The Airports Authority of India (AAI) serves as the nodal agency responsible for its implementation.

- Provision of subsidies: Under the UDAN Scheme, the government works in partnership with airlines to provide subsidies and incentives to operate flights on underserved and unserved routes.

- Works on VGF model: The government provides financial support to airlines through a Viability Gap Funding (VGF) model, which covers the difference between the cost of operations and the expected revenue on the identified routes.

- Use of bidding: Aviation companies bid for air routes. The company that asks for the lowest subsidy is awarded the contract. Under this fare for each flight, the airline has to book half, or a minimum of 9, or a maximum of 40 seats.

- Capping of price: Under the scheme, the airfare for a one-hour journey by a ‘fixed wing aircraft’ or half an hour’s journey by a helicopter for about 500 km has been fixed at Rs.2500.

Source:

Category: Polity and Governance

Context:

- The Supreme Court Collegium’s unexpected change of mind to recommend a MP High Court judge for the Allahabad High Court, in compliance with the Centre’s wishes has brought back into focus executive interference in judicial appointments.

About Collegium System:

- Nature: It is India’s judicial mechanism for appointing and transferring judges to the Supreme Court and High Courts. It is not a direct constitutional provision but evolved from landmark Supreme Court judgments, most notably the “Three Judges Cases”.

- Evolution:

- First Judges Case (1981): SC held that in the appointment of a judge of the SC or the HC, the word “consultation” in Article 124(2) and in Article 217 of the Constitution does not mean “concurrence”. It gave the executive primacy over the judiciary in judicial appointments.

- Second Judges Case (1993): The SC overruled the First Judges Case and held that “consultation” in judicial appointments actually meant concurrence. The SC ruled that the CJI’s advice on appointing judges is binding on the President. Before giving this advice, the CJI must consult their two senior-most colleagues.

- Third Judges Case (1998): The SC expanded the Collegium to include the CJI and the 4 most senior judges of the court after the CJI.

- National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act, 2014: It was brought to replace the existing collegium system for appointing judges. However, a five-judge Constitution Bench declared it as unconstitutional and nullified it, stating that it posed a threat to the independence of the judiciary.

- Constitutional basis for appointment of judges:

- Article 124: SC judges appointed by the President in consultation with the Chief Justice of India (CJI) and other judges.

- Article 126: In case of vacancy/absence, senior most available SC judge appointed by the President.

- Article 127: If quorum of SC judges is not available, CJI (with President’s consent) can request a HC judge to sit in SC.

- Article 128: With President’s consent, CJI may request a retired SC judge to sit and act as SC judge for a specified period.

- Article 217: HC judges appointed by the President in consultation with CJI, Governor, and HC Chief Justice.

- About Memorandum of Procedure (MoP):

- The MoP is the list of rules and procedures for the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court and the high courts. It is a document framed by the government and the judiciary together. The Union government framed an MoP on 30 June 1999.

- The current MoP gives out the detailed procedure for the appointment of Supreme Court and high court judges. It states that all appointments of judges to the Supreme Court must be recommended by the Collegium, composed of the Chief Justice of India and the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court. This recommendation is then sent to the central government. The law minister will forward it to the prime minister, who is to advise the President on the appointment.

- Revised MoP: In 2015, the Supreme Court instructed the central government to develop a new MoP to ensure transparency in the collegium’s proceedings. In 2017, although the MoP was finalized, the government did not adopt it, citing a need to reconsider the matter.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(GS Paper 3 – Infrastructure: Energy, Renewable Energy, and Environmental Conservation)

Context (Introduction)

India has emerged as the world’s third-largest solar power producer, with rapid growth in capacity and domestic manufacturing. However, sustaining this progress requires expanding exports and leveraging international partnerships, particularly in Africa, through the International Solar Alliance framework.

Main Arguments

- Rapid Solar Expansion: India’s solar generation reached 1,08,494 GWh in 2024–25, surpassing Japan and trailing only China and the U.S. Installed solar capacity rose from 2 GW in 2014 to 117 GW in 2025, with manufacturing capacity projected at 100 GW (effective 85 GW).

- Falling Costs and Competitiveness: Since 2017, solar power became cheaper per unit than coal, attracting large-scale investments. Yet, Indian modules remain 1.5–2 times costlier than Chinese ones due to scale inefficiencies, limited raw material access, and weaker production lines.

- Domestic Climate Commitments: India’s 2030 goal is to source 50% of power from non-fossil fuels (≈500 GW), with 250–280 GW from solar. However, annual additions average only 17–23 GW, short of the required 30 GW/year pace.

- Export and Global Market Potential: India’s exports of 4 GW in 2024 to the U.S. were temporary, while China exported 236 GW in the same period. To sustain its growing industry, India needs stable external markets. Africa presents a promising destination through the International Solar Alliance (ISA) framework.

- Africa Opportunity: Africa’s power deficit leaves 96% of arable land non-irrigated. India can offer affordable solar pumpsets and decentralized solar systems, modeled on PM-KUSUM (rural solar) and PM-Surya Ghar (urban rooftop solar) schemes, aligning energy access with developmental cooperation.

Criticisms / Challenges

- High Production Costs: Indian solar modules are less competitive globally due to import dependence on polysilicon, wafers, and cells, and high logistics costs.

- Policy Uncertainty: Frequent changes in import duties, PLI scheme delays, and inconsistent state-level solar policies discourage long-term investment.

- Weak Domestic Demand Uptake: Flagship schemes like PM-KUSUM and PM-Surya Ghar have seen low disbursal and adoption rates, limiting domestic consumption of solar modules.

- Limited Technological Depth: Indian manufacturers largely rely on assembly-based production, with minimal R&D in high-efficiency solar cells (e.g., TOPCon, HJT, perovskite technologies).

- Global Competition: China’s dominance—through scale, subsidies, and supply chain control—makes it difficult for India to penetrate established export markets.

Reforms and Way Forward

- Strengthen Global Alliances: Use the International Solar Alliance (ISA) to institutionalize India-Africa partnerships in solar deployment, finance, and capacity building.

- Enhance Competitiveness: Expand the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme to cover the entire value chain (polysilicon to module). Encourage joint ventures for technology transfer.

- Create Export Hubs: Establish Solar SEZs and green corridors near ports to boost export readiness and logistics efficiency.

- Financial and Policy Stability: Ensure stable tariffs, predictable policy regimes, and easy credit for developers under Renewable Energy Development Agencies.

- Domestic Scaling through Innovation: Integrate solar with agriculture (solar pumpsets, cold storage) and urban housing (rooftop grids) to expand domestic utilization and reduce per-unit costs.

Conclusion

India’s solar sector stands at a pivotal moment — transitioning from self-reliance to global competitiveness. By bridging policy gaps, enhancing value-chain depth, and fostering South–South cooperation through the ISA, India can evolve into a credible global supplier of solar solutions, aligning industrial growth with climate justice.

Mains Question:

“India’s success in solar energy production must now translate into global competitiveness. Examine the challenges and opportunities for India to emerge as a key solar power supplier, especially to developing regions like Africa.” (250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Hindu

(GS Paper 2 – Governance: Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation)

Context (Introduction)

While reversing brain-drain in STEM is a valid goal, India’s ambition for higher education must be broader than simply producing industrial pipelines. True academic strength lies in inquiry, autonomy, interdisciplinarity and openness—not just strategic STEM nationalism.

Main Arguments

- Repatriation of talent has limits. The proposed scheme to attract Indian-origin “star faculty” targets 12-14 priority STEM areas, offering grants and labs to returnees. Yet the article emphasises that this is only a beginning: what matters more is the environment that enables sustained contribution at home.

- India already has strong institutions but needs reinforcement. Institutions like Indian Institute of Technology’s (IITs), Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) and others have produced notable work despite constraints. The article argues these must be bolstered by sustained investment, transparent governance and genuine academic autonomy.

- Higher education should not be reduced to industrial supply-chain logic. The piece cautions against treating universities merely as feeders for industry and emphasises that innovation “flourishes in interdisciplinary, and often inconvenient spaces” — for instance where social scientists question the ethics of AI, or historians challenge majoritarian narratives.

- Academic freedom and openness are essential. Returnees and ongoing faculty must have the freedom to ask difficult questions. The article invokes the example of deportation of scholars (e.g., Francesca Orsini) as sending “a dispiriting message about how India treats academic inquiry that doesn’t align with official narratives”.

- Global benchmarks show India’s lag. China’s Thousand Talents Plan (launched 2008) was accompanied by systemic overhaul of its universities — resulting now in five Chinese institutions in the QS Top 100, 72 overall. In contrast, India with 54 institutions is yet to break into the Top 100; the highest-ranked Indian institution, IIT Delhi, stands at 123.

Criticisms / Drawbacks

- Over-emphasis on STEM and strategic priorities. While targeting STEM is understandable, reducing higher education to strategic national capacities (AI, quantum computing, biotech) risks marginalising humanities and social sciences, which are essential for ethical, reflective, societal dimensions of innovation.

- Institutional autonomy remains weak. Political interference, curricular controls and faculty appointments driven by patronage hamper universities.

- Retention and attractiveness issues. Even if returning faculty can be recruited, without robust institutional ecosystems, many may view India as a stop-gap rather than a long-term base — undermining the ambition to build a home for them.

- Neglect of critical social sciences. In pursuing technological self-reliance and national competitiveness, ignoring the role of ethics, philosophy, social inquiry and interdisciplinary scholarship diminishes holistic education.

- Global perception and ranking gap. Despite quantity in enrolments and STEM graduates, Indian higher-ed institutions struggle to achieve global research impact, innovation culture and institutional prestige.

Reforms and Way Forward

- Strengthen academic autonomy and governance. Universities must have freedom in curriculum design, faculty appointment, research priorities and institutional direction — insulated from excessive political or regulatory control.

- Balance STEM with humanities and interdisciplinary research. Foster environments where technology is informed by ethics, society, culture and history. Encourage programmes that integrate engineering-science with social science/humanities (as argued in “A Lesson from IIT” article).

- Build institutional ecosystems, not just recruit stars. Ensure returning scholars find high-quality labs, stable funding, peer communities, long-term contracts, and an environment that values inquiry.

- Raise research investment and culture. Increase R&D spend (currently low relative to global peers), promote high‐quality PhDs, encourage risk-taking, support basic research not purely applied/industrial outcomes.

- Global engagement and openness. Protect academic freedom, welcome diverse ideas (including dissenting ones), avoid deportations or political pressures on scholars. Offer competitive remuneration, world-class infrastructure, and reputational incentives to retain domestic talent.

- Monitor and reform metrics of success. Shift from narrow metrics (graduates-for-industry, placements) to broader ones: research quality, citation impact, interdisciplinary output, global collaborations, societal relevance.

Conclusion

India stands at a crossroads in higher education. The effort to reverse brain‐drain and build global research capacity is commendable, but it must be accompanied by a deeper transformation: from a narrowly instrumental model — “university as industry feeder” — to a vibrant ecosystem of inquiry, autonomy, interdisciplinarity and openness.

Only then can India not just stock its strategic STEM needs, but truly nurture minds that question, innovate, reflect and lead, building institutions that command global respect and serve society in full.

Mains Question

- India’s higher education is increasingly focused on strategic STEM development. Examine the opportunities and challenges of this approach, and suggest measures to ensure academic freedom and societal relevance. (250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Indian Express