IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis

Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: Defence and Security

Context:

- The Defence Acquisition Council, recently accorded Acceptance of Necessity (AoN) for capital acquisition proposals worth approximately ₹3.60 lakh crore.

About Defence Acquisition Council:

- Nature: It is the highest decision-making body of the Defence Ministry on procurement.

-

- Objective: The main objective of the DAC is to ensure expeditious procurement of the approved requirements of the armed forces in terms of capabilities sought and time frame prescribed by optimally utilizing the allocated budgetary resources.

- Formation: It was formed after the Group of Minister’s recommendations on ‘Reforming the National Security System’, in 2001, post-Kargil War (1999).

- Composition: It is chaired by Defence Minister and the other key members include the Minister of State for Defence, Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), Chiefs of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, Secretaries of various Defence departments, and the Director General (Acquisition), and Member Secretary: Dy. Chief of Defence Staff (PP&FD).

- Significance: The DAC is central to India’s Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) 2020, aiming to boost domestic defence manufacturing. While it is the top body for procurement, the final financial approval for very large deals rests with the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS), chaired by the Prime Minister.

- Key Functions:

-

- Give in principle approval of a 15-year Long Term Integrated Perspective Plan (LTIPP) for defence forces.

- Accord of acceptance of necessity to acquisition proposals.

- Categorisation of the acquisition proposals relating to ‘Buy’, ‘Buy & Make’, and ‘Make’.

- Look into issues relating to single vendor clearance.

- Take decisions regarding ‘offset’ provisions in respect of acquisition proposals above Rs 300 crore.

- Take decisions regarding the Transfer of Technology under the ‘Buy & Make’ category of acquisition proposals.

- Field trial evaluation.

Source:

Category: Environment and Ecology

Context:

- Researchers cautioned that the increase of lion‑tailed macaques in human-dominated landscapes is driven largely by easy access to food associated with human presence.

About Lion‑Tailed Macaques:

- Nature: It is an Old World monkey.

-

- Other names: It is also known as the ‘beard ape’ because of its mane.

- Nomenclature: The magnificent Lion-tailed macaque is named due to its lion-like, long, thin, and tufted tail.

- Appearance: They are characterised by the grey mane around their face.

-

- Uniqueness: It is one of the smallest macaque species in the world.

- Distribution: It is endemic to evergreen rainforests of the southern part in Western Ghats, with its range passing through the three states of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

- Habitat: It is an arboreal and diurnal creature, they sleep at night in trees (typically, high in the canopy of rainforest).

- Distinguishing feature: These macaques are territorial and very communicative animals. One of the distinguishing features of this species is that males define the boundaries of their home ranges by calls.

- Communication system: Overall, their communication system is composed of as many as 17 vocalisations.

-

- Diet: It is omnivorous and feeds upon a wide variety of food, although fruits form the major part of their diet.

- Conservation Status:

-

- IUCN: Endangered

- CITES: Appendix I

- The Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972: Schedule I.

Source:

Category: History and Culture

Context:

- Two researchers recently identified close to 30 inscriptions in Tamil Brahmi, Prakrit and Sanskrit at tombs in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt.

About Valley of the Kings:

-

- Nature: It was the burial site of dozens of pharaohs, or kings, of ancient Egypt.

- Location: The valley lies in the southern half of Egypt, just west of the Nile River. It was part of the ancient city of Thebes.

- Significance: Most of the pharaohs of the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties were buried in the Valley of the Kings. These pharaohs ruled from 1539 to 1077 BC, during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom.

- Largest: The tomb built for the many sons of Ramses II is the largest and most complex in the valley.

- Terrain: The tombs in the Valley of the Kings were carved into rocky hillsides with only a doorway marking their location.

- Interior: The interior varied from tomb to tomb, but most consisted of a series of descending corridors with multiple openings leading to chambers, or rooms.

- Use of corridor: Deep underground, one corridor ended at the burial chamber. It held a sarcophagus, or stone coffin, in which the pharaoh’s mummy was laid.

- Objects: The burial chamber also included furniture, clothing, jewelry, and other items that it was believed the pharaoh would need in the afterlife.

- Denudation: Virtually all the tombs in the valley were cleared out in antiquity. Some had been partially robbed during the New Kingdom, but all were systematically denuded of their contents in the 21st dynasty, in an effort to protect the royal mummies and to recycle the rich funerary goods back into the royal treasury.

- Mostly intact: The only tomb to remain mostly intact was that of Tutankhamun (reigned 1333–24 BC).

- Uniqueness: In 1979, UNESCO made the Valley of the Kings part of the World Heritage site of ancient Thebes.

Source:

Category: Miscellaneous

Context:

- India has been ranked 91st out of 182 countries and territories on the Corruption Perceptions Index for 2025, released recently.

About Corruption Perceptions Index:

-

- Nature: It is the most widely used global corruption ranking in the world.

- Objective: It measures how corrupt each country’s public sector is perceived to be, according to experts and business people.

- Publishing agency: The index has been published by Transparency International, a Berlin-based non-governmental organisation (NGO).

- Frequency: It has been published annually since its inception in 1995.

- Methodology used: It ranks countries “by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys.”

- Scale: It uses a scale of zeo to 100, where “zero” is highly corrupt and “100” is very clean. The score for each country is derived from a minimum of three data sources, selected from 13 distinct corruption surveys and assessments.

- Sources: These sources are gathered by a range of reputed organisations, such as the World Bank and the World Economic Forum.

- Key highlights of Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2025:

-

-

- Least Corrupt nations: Denmark, Finland and Singapore.

- Most Corrupt nations: South Sudan, Somalia and Venezuela.

-

- Performance of India: Its rank improved from 96 (2024) to 91 (2025).

Source:

Category: Geography

Context:

- Recently the Stanford researchers have produced the first global map of a rare type of earthquake i. e Continental mantle earthquakes.

About Continental Mantle Earthquakes:

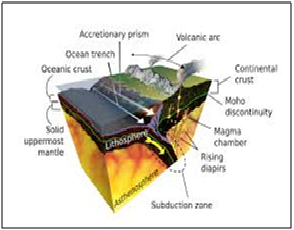

- Nature: These are seismic events which originate in the mantle beneath continents.

-

- Origin: They occur in the mantle lithosphere, significantly deeper than standard crustal earthquakes.

- Identification method: Scientists distinguish them using a waveform-based method that compares Sn waves (which travel through the mantle) and Lg waves (which travel through the crust). A high Sn/Lg ratio indicates a mantle origin.

- Global distribution: While rare (only 459 confirmed globally since 1990), they are regionally clustered. Major clusters lie Beneath the Himalayas (Southern Asia) and the Bering Strait (between Asia and North America), other locations include Italy, Tibet, the Caucasus, East Africa, Alaska, and Idaho.

- Difference with common earthquakes: Unlike most earthquakes, which originate in the Earth’s cold, brittle crust at depths of around 10 to 29 kilometres, mantle earthquakes often occur more than 80 km below the Mohorovičić discontinuity (boundary between the crust and the mantle).

- Impact: Due to their extreme depth, they typically cause minimal shaking or danger at the Earth’s surface.

- New observation: Their existence proves the mantle is not purely ductile (plastic-like) but can host brittle-like failures, challenging the view that seismicity is confined to the crust.

- Significance: The new map will help scientists learn more about the mechanics of mantle earthquakes.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(GS Paper II – Judiciary; Government policies and interventions for vulnerable sections; Issues relating to women and gender justice)

Context (Introduction)

Recent remarks questioning the Supreme Court’s gender glossary as being “Harvard-oriented” have triggered debate on the institutional commitment to gender justice. The controversy is not merely about terminology, but about whether the judiciary should institutionalise gender-sensitive practices as part of its constitutional mandate under Articles 14, 15 and 21.

Context of the Gender Glossary

- Purpose of the Glossary: The gender glossary was designed as a practice guideline to promote gender-sensitive language in judicial orders and proceedings.

- Addressing Humiliation: It sought to prevent secondary victimisation of survivors through stereotypical or insensitive judicial language.

- Constitutional Foundation: The initiative aligned with Article 15, which prohibits discrimination on grounds of sex, and with the broader right to dignity under Article 21.

- Institutional Memory: Practice directions function as tools of judicial continuity, ensuring consistency across hierarchies of courts.

- Administrative Authority: The Supreme Court is empowered to frame rules and guidelines as part of its institutional role under the Constitution.

Significance of Gender-Sensitive Judicial Language

- Language as Norm-Setting: Judicial language shapes social values and influences how justice is perceived and delivered.

- Preventing Bias: Gender audits of legal language help eliminate embedded stereotypes that may undermine fairness.

- Access to Justice: Sensitive terminology ensures that survivors of sexual violence are not retraumatised during proceedings.

- Systemic Reform: Such guidelines aim at “last-mile delivery” of justice by guiding magistrates, sessions courts and high courts.

- International Commitments: India’s obligations under CEDAW and other conventions reinforce the need for gender-responsive judicial processes.

Issues Raised in Discarding the Glossary

- Lack of Institutional Consultation: The withdrawal reportedly occurred without structured engagement with the bar or affected communities.

- Technical Language Argument: The claim that the glossary was “too technical” appears inconsistent with the inherently technical nature of legal discourse.

- Institutional Continuity Concern: Abrupt policy reversals risk undermining predictability and coherence in judicial functioning.

- Decolonisation Debate: The criticism of being “Harvard-oriented” reflects broader tensions around decolonisation versus global legal engagement.

- Balancing Swadeshi and Universalism: Constitutional values allow borrowing best practices from global jurisprudence while contextualising them domestically.

Broader Constitutional Implications

- Equality and Dignity: Gender-sensitive judicial conduct is an extension of substantive equality jurisprudence developed by the Supreme Court.

- Judicial Role in Social Reform: Courts have historically advanced gender justice in cases relating to workplace harassment, triple talaq, and entry restrictions.

- Institution vs Individual Judges: Institutional guidelines prevent justice from being dependent solely on individual judicial discretion.

- Trust in Judiciary: Stable, transparent practice directions strengthen public confidence in judicial impartiality.

- Risk of Regression: Diluting progressive guidelines may weaken gains made in gender justice over decades.

Way Forward

- Structured Judicial Dialogue: Convening judicial conclaves or consultations with the bar and civil society can refine rather than discard such guidelines.

- Gender Audit Mechanism: Periodic review of judicial language and practices can institutionalise sensitivity without overreach.

- Training and Capacity Building: Incorporating gender modules in judicial academies ensures consistent implementation.

- Contextual Adaptation: Guidelines may be simplified or localised while retaining core principles of dignity and equality.

- Balancing Reform and Legitimacy: Institutional reforms must be transparent to maintain judicial credibility.

Conclusion

The debate over the gender glossary is ultimately about whether gender justice should remain dependent on individual judicial philosophy or be embedded within institutional practice. In a constitutional democracy committed to equality and dignity, strengthening — not weakening — institutional safeguards for gender justice remains imperative.

Mains Question

- Stereotype, Prejudice and discrimination are embedded in the structure and vocabulary of language. In this light, critically examine the role of judiciary in forwarding gender justice through its judgements and guidelines (250 words)

Source: Indian Express

(GS Paper III – Infrastructure: Energy; Science and Technology; Environmental Impact Assessment; Disaster Management)

Context (Introduction)

The SHANTI Act marks a structural shift in India’s nuclear power policy by opening the sector to private operators and amending the liability framework under the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (CLNDA), 2010. The legislation alters supplier liability, caps compensation, and modifies regulatory oversight, raising concerns regarding safety, accountability and constitutional principles of absolute liability in hazardous industries.

Key Provisions of the SHANTI Act

- Private Participation: The Act permits private entities to operate nuclear power plants, ending the earlier regime of exclusive Union government control.

- Supplier Indemnification: It removes the operator’s “right of recourse” against suppliers for defective equipment, thereby shielding suppliers from civil liability.

- Liability Cap: Operator liability is capped between ₹100 crore (small plants) and ₹3,000 crore (large plants), with a total accident liability cap of 300 million Special Drawing Rights (≈ ₹3,900 crore).

- Removal of Clause 46: Victims cannot invoke other civil or criminal laws for additional remedies beyond the statutory cap.

- Regulatory Framework: The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) receives statutory backing but its independence is constrained as appointments are routed through the Atomic Energy Commission.

Changes from the CLNDA Framework

- Erosion of Right of Recourse: Section 17(b) of the CLNDA allowed operators to sue suppliers for accidents caused by defective equipment; this safeguard is omitted.

- Dilution of Absolute Liability: The Act indemnifies operators in cases of “grave natural disasters,” despite precedents such as the Fukushima disaster (2011), which was tsunami-triggered.

- Capped Compensation Regime: India moves closer to supplier-friendly international conventions, including the Convention on Supplementary Compensation (CSC).

- Alignment with External Pressure: The 2026 U.S. National Defense Authorization Act sought India’s alignment with global liability norms favourable to suppliers.

- Reduced Litigation Space: The removal of Clause 46 narrows victims’ access to alternative legal remedies.

Liability Cap vs. Potential Damage

- Comparative Scale: Fukushima-related costs are estimated at ₹46 lakh crore, while Chernobyl losses to Belarus alone were around ₹21 lakh crore.

- Exclusion Zone Impact: The Chernobyl exclusion zone (area comparable to Goa) remains uninhabitable decades later.

- Magnitude Gap: India’s liability cap of ~₹3,900 crore is roughly 1/1000th of the economic damage seen in major nuclear accidents.

- Limited Supplementary Funds: Even with CSC assistance, compensation would remain under 1% of potential catastrophic losses.

- Risk Transfer to Citizens: Victims would bear the residual burden of losses beyond the statutory cap.

Moral Hazard and Safety Concerns

- Incentive Distortion: Shielding suppliers and limiting liability reduces incentives for rigorous safety design and quality control.

- Historical Precedents: Design defects were central in Fukushima nuclear disaster, Chernobyl disaster, and Three Mile Island accident.

- Regulatory Weakening: Limited independence of AERB may undermine robust oversight.

- Reversal of Absolute Liability Doctrine: India’s environmental jurisprudence traditionally favours strict accountability in hazardous industries.

- Disaster Preparedness Concerns: Liability dilution may weaken incentives for resilient infrastructure against climate-linked risks.

Nuclear Energy in India: Reality Check

- Marginal Contribution: Nuclear energy contributes only about 3% of India’s electricity generation.

- Missed Targets: Targets of 10 GW by 2000 and 20 GW by 2020 were missed; actual capacity was 2.86 GW (2000) and 6.78 GW (2020).

- High Capital Costs: Nuclear plants require massive upfront investment and long gestation periods.

- Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): Proposed expansion relies on largely untested and capital-intensive SMR technology.

- 2047 Target: The goal of 100 GW by 2047 appears ambitious given historical performance.

Economic and Strategic Implications

- Commercial Opportunity: Large-scale reactor projects such as Westinghouse AP1000 reactors in Georgia (≈ $18 billion each) illustrate the scale of potential contracts.

- Supplier Confidence: Indemnification may attract multinational suppliers and private capital.

- Risk Socialisation: Profit is privatised while catastrophic risk is socialised.

- Energy Diversification Argument: Nuclear is projected as a clean baseload alternative to fossil fuels.

- Climate Commitments Context: Expansion aligns with India’s decarbonisation goals but raises safety governance questions.

Conclusion

The SHANTI Act represents a policy trade-off between attracting private investment in nuclear energy and preserving robust accountability mechanisms. While aligning with international supplier-friendly norms may facilitate expansion, the dilution of liability safeguards risks creating moral hazard and transferring catastrophic risks to citizens. Given nuclear power’s modest contribution to India’s energy mix and historical capacity shortfalls, the long-term prudence of weakening liability standards demands rigorous scrutiny.

Mains Question

- Critically examine the implications of the SHANTI Act on nuclear liability, safety governance, and India’s energy transition strategy. Does capping liability create moral hazard in high-risk sectors like nuclear energy? (250 words)

Source: The Hindu