IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs April 2017, IASbaba's Daily News Analysis, UPSC

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 27th April 2017

Archives

SOCIAL ISSUE

TOPIC:

General Studies 2

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

General Studies 3

- Conservation, Environmental pollution and degradation, environmental impact assessment.

- Economic Development, Bio diversity, Environment, Security

Tribal Rights and Ecology

Introduction

India being a diverse landmass with a huge forest area faces competing challenges and priorities. It is significant to uphold the tribal rights and include them in ecological conservation. An exclusionary policy is detrimental and not in line with spirit of the Forest rights act.

Issue:

The National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) recently ordered that there would be no tribal rights under the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (FRA) in critical tiger habitats.

- The direction is against the spirit of the law and is also symbolic of defective conservation practices prevalent in India.

- It has added to actions that are breaching environmental protection and hard-won rights under the FRA every day.

Law in perspective:

- Both the ‘Guidance document for preparation of tiger conservation plan’ and the ‘Protocol/guidelines for voluntary village relocation in notified core/critical tiger habitats of tiger reserves’ issued by the Environment Ministry acknowledge that although there is a need to keep forest reserves as inviolate for the purposes of tiger conservation.

- This must be done without affecting the rights of traditional forest dwellers.

- The NTCA and the relevant expert committee constituted to ensure tiger conservation under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (WPA) have a mandate to ensure conservation along with human coexistence.

- Compromises on the rights of tribals can be made only where there is proof that the tribal/right holder’s presence in these protected areas will create irreversible damage to their ecology.

- While on paper the process adopted or recommended for creation and maintenance of critical tiger habitats appears fairly just, in effect its functioning is arbitrary.

Tribes and forest rights:

- Neither the FRA nor the WPA has ever made a case for circumscribing the rights of tribals in the name of environmental protection.

- Yet this takes place as the practice of conservation is predicated on exclusionary logic.

- Even in the face of significant evidence that tribals have helped in increasing the tiger population, whether the Soligas in the BRT Tiger reserve in Karnataka or the Baigas in the Kanha National Park in M.P. they have been periodically evicted, even as corporations and developmental projects are given a free hand to generate an environmental crisis on an unprecedented scale.

Encroachment and Environmental justice:

- In Karnataka recently, a place of worship for Huligemma, one of the indigenous deities of tribals in Bandipura, was ‘renovated’.

- The earlier modest shack, occupying little space, was replaced by a temple that was nearly three times its size.

- This will not only obstruct the passage of animals to waterholes but also allow expansion of commerce.

- Even as questions are being raised about the breach of law in allowing the structures to exist, the government has feigned ignorance.

- This reveals the hypocrisy embedded in environmental governance where the strictness of law is manifest only in excluding people whose presence has nearly negligible impact on environmental security.

- According to the Global Environmental Justice Atlas data of 2016, India registered the highest number of environment-related conflicts (222) in proportion to the population.

- It is thus necessary for civil society and peoples’ collectives to forge an alliance to prevent dissociating indigenous communities from the environmental conservation narrative.

Conclusion:

In India a balance between environmentalism and development is a basic necessity. Strengthening the FRA and eliminating instances that marginalize people in the name of conservation will require greater policy attention. Rights of the vulnerable and marginalised community like the tribals especially because they are voiceless is significant.

Connecting the dots:

- Analyse the working of Forest rights act and the challenges in ensuring rights in the phase of development push observed in India.

ECONOMY/TOURISM

TOPIC: General Studies 2

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment.

- Tourism and related issues.

India’s tourism potential and World Economic Forum’s (WEF’s) travel and tourism competitiveness index

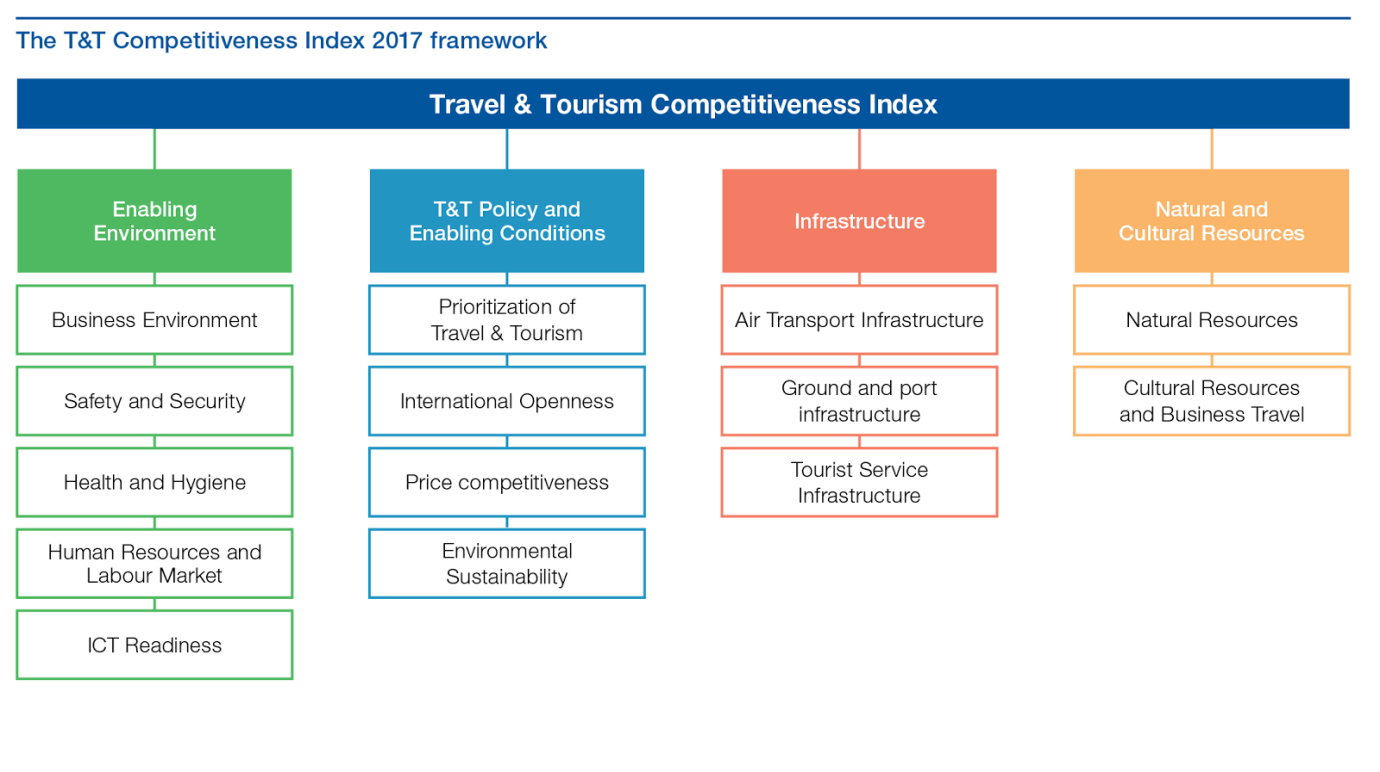

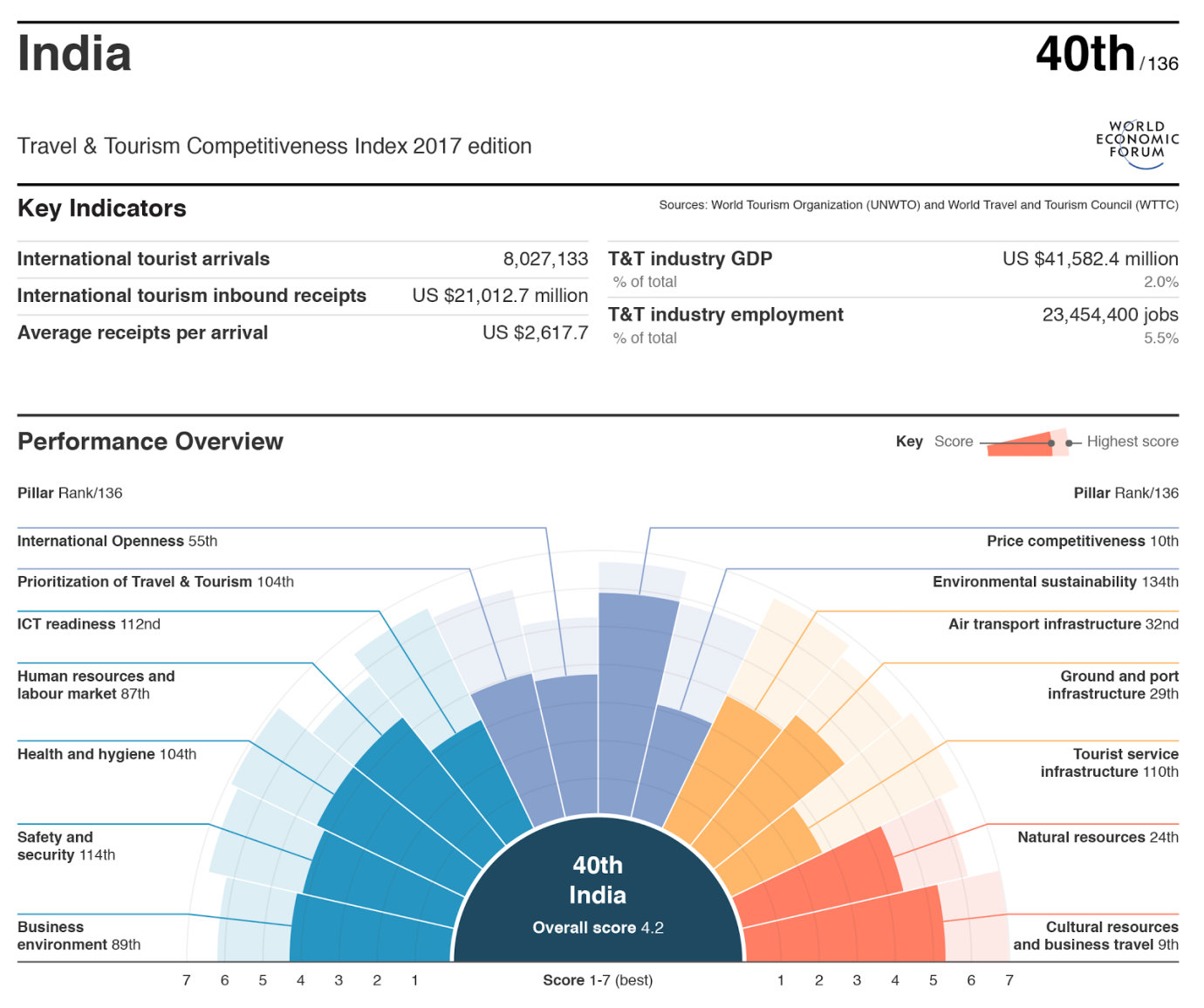

Recently released World Economic Forum’s (WEF’s) travel and tourism competitiveness index (TTCI) showed that India had moved up 12 places and now ranks 40th among 136 nations globally.

The report also noted that this was the largest leap made by any country in the top 50, thereby making India, with its rich and diverse cultural heritage and natural beauty, a prime candidate to lead the so-called Asian century in travel and tourism.

Link: http://mediaindia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/WEF_TTCR_2017-16_INDEX.jpg

Assessment: So much for potential—but will India deliver? What are the issues? Why India’s tourism potential still largely untapped?

India’s performance in this regard tells a complex story.

On the one hand, foreign tourist arrivals have been on an upward trajectory at least since the turn of the century.

- According to the ministry of tourism, India hosted 8.89 million tourists last year compared to only 2.65 million tourists in 2000.

But when compared with other countries, India’s performance leaves much to be desired.

- For example, while India hit an all-time high last year, it was still nowhere close to France, which topped the list of foreign tourist arrivals with 84.5 million visitors. The US (77.5 million) was second, followed by Spain (68.2 million), China (56.9 million) and Italy (50.7 million).

- India lags behind its other Asian peers like Japan (4th) and China (13th).

Europe’s dominant position on the list can be explained through the Schengen agreement, which allows citizens of member states to travel freely across international borders.

The US too has a visa-waiver agreement with most European Union countries as well as a handful of others for easy access.

But non-Schengen states like China—or, for that matter, Turkey (39.4 million tourists in 2015), Mexico (32.1 million) and Russia (31.3 million) have significantly higher tourist numbers than India.

Tourism contribution to India’s economy:

India’s foreign exchange earning from tourism has followed a similar pattern.

- In 2015, for example, India earned more than $23 billion in revenue from international tourism, a significant hike from the $3.5 billion it made in 2000. However, the US earned $204.5 billion from international tourists and China $114.1 billion, in 2015—making India’s $23 billion seem like chump change.

However, while overall revenue from tourists in India is low because of fewer visitors, the average revenue per tourist is actually quite high.

- For example, while the average tourist spends about $2,639 in the US, he/she spends about a comparable $2,610 in India and about $2,005 in China. In France (and this is generally true for other European countries as well), the number drops to $543 per tourist.

This is because a large chunk of the tourists visiting France are other Europeans with Schengen privileges on short trips from across the borders. But while such tourists add to the numbers, they don’t always spend a lot of money.

In contrast, when a French or German tourist takes a long-haul flight to India for what is ostensibly a well-planned holiday, they tend to stay longer and spend more money.

For India, this is not as much a success story as much as it is an indication of a missed opportunity: When they are here, tourists are clearly willing to spend; but they are simply not coming here in adequate numbers in the first place.

Positives:

India continues to allure international tourists with its vast cultural and natural resources with a ranking of 9th and 24th respectively. In terms of price competitiveness advantage, India is ranked 10th.

India continues to enhance its cultural resources, protecting more cultural sites and intangible expressions through UNESCO World Heritage lists, and they also increasing their digital presence.

India is ranked 55th, up by 14 places in terms of international openness, which has been possible through stronger visa policies. Implementing both visa-on-arrival and e-visa has enabled India to rise through the ranks.

The key reasons for India’s jump in the Travel and Tourism Competitive Index 2017 should be attributed to the pro-active steps taken by the Indian Government in terms of the development of tourism infrastructure and easing of entry formalities for tourists by introducing the e-visa facilities.

Why India’s tourism potential still largely untapped?

- Quality is vital for a successful tourism industry. A rapid growth in alternative destinations worldwide means that India’s tourism industry today faces the need to be ever more quality conscious to continue to attract tourists in a global marketplace.

- Although around 89,500 additional rooms (to the existing 80,000 rooms) are expected to come up in India in the next five years, the supply of quality rooms in India is much lower compared to other countries across the globe.

- There is still a negative perception about India as a safe destination for female foreign tourists.

- Land acquisition is one of the single largest roadblocks for development of infrastructure. Lack of proper dispute resolution mechanism adds to the delays. Disputes often lead to lengthy litigation and substantial project delays.

- Inadequate regulatory framework and inefficiency in the approval process.

- Inadequate efforts to promote tourism aggressively.

- Lack of automated immigration procedures for the processing of arrivals at ports of entry to facilitate improved time efficiency.

- Ensuring ancillary infrastructure issues such as taxi-cabs that connect airports and hotels are always safe, clean, licensed and in ample supply.

- Lack of basic hygienic amenities at halting points.

- Lack of economic rationale for preserving the ordinary cultural heritage.

- Limited professional capacity. (Providing training to develop skills to enhance visitor experiences, restore or expand heritage sites, build exhibits and interpret themes and train guides)

Problems such as cumbersome visa regulations, bad travel infrastructure, poor sanitation, collapsing law enforcement systems and concerns about women’s safety. On each of these counts, India ranks poorly on the WEF index.

Link: http://mediaindia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/WEF_TTCR_2017-200_INDIA.jpg

Other factor is majority of visitors to India are business tourists (who expectedly are high-spenders and takes five-star route). It is worth questioning whether India is getting its fair share of budget travellers especially since it is otherwise one of the most affordable travel destinations? Are middle-class tourists, who want a certain degree of comfort and hassle-free travel but cannot afford to go the five-star route, staying away?

If true, that is another challenge for India as it will have to prepare for the changing profile of the international tourist. As the WEF report notes, foreign travel is no longer a luxury enjoyed only by wealthy Westerners. The lowering of trade barriers and the rise of the middle class in many emerging economies mean that North America and Europe, which have dominated the travel markets till now, may give way to international travel from Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Currently, India receives the maximum number of tourists from the US, followed by Bangladesh, while regionally, Western Europe and North America make up for a large chunk of the country’s foreign tourists—at 23.42% and 18.62% in 2015, respectively. South Asia tops the list with 24.25% but that is to be expected given that it is India’s neighbourhood.

What is of concern though is that other regions that are expected to send out tomorrow’s tourists don’t seem to have India on their radar.

- In 2015, only 8.72% of India’s foreign tourists were from South-East Asia while East Asia made up 6.92%, West Asia 5.20%, Eastern Europe 4.12%, Australasia 3.89%, Africa 3.66% and Central and South America, 0.88%.

Conclusion:

The silver lining here is that all these regions, except Eastern Europe, have been sending more tourists to India than before. The government should be cognizant of the fact that a lot more needs to be done on the home front. It has to start by liberalizing the visa regime which is expected to improve the numbers quickly. But that’s only the first step. Making it easier to visit India won’t do much when being a tourist in India is replete with problems.

Connecting the dots:

- The potential of tourism industry in India remains untapped despite efforts made by successive governments since independence. Suggest what proactive measures are needed to revive this sector.

- Critically examine the potential of India’s tourism sector in generating foreign exchange earnings and employment generation.

MUST READ

Navigating between friends

A solution in search of a problem

Hedging bets as Trump scouts for deals

The Blind Men Of Niti Aayog

India’s medieval counter-insurgency

Why India needs big new cities

Indian heritage’s economic potential

Economically responsible justice

Broadband through cable networks