IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs June 2017, IASbaba's Daily News Analysis, National, UPSC

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 14th June 2017

Archives

NATIONAL

TOPIC: General Studies 3

- Infrastructure: Energy

- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment.

India’s Energy Transformation

India has gained global attention for its ambitious clean energy targets. India is now expected to play a major role in global energy transformation, by maintaining its own pledges, holding to account the developed world and thus, building global confidence.

India has become a frontrunner in energy transformation:

- India added more renewable energy (RE) capacity than conventional generation capacity in 2016-17.

- RE tariff in the country dropped to a level that is cost competitive with coal-fired generation.

- According to EY’s renewable energy country attractiveness index, India pipped the US to become the second most attractive country for RE investments.

- According to government data, the share of renewable energy in the total installed capacity was 13% at the end of financial year 2016. But it is expected to increase significantly in the coming years, with solar a big driver.

Ambitious targets:

- In 2014, the domestic RE target was revised to 175 GW of installed capacity by 2022.

- In 2015, in its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDC), India made a global pledge to achieve 40% cumulative installed capacity from fossil-fuel-free resources by 2030.

- The country already has 33% fossil-fuel-free generation capacity, and as predicted by Central Electricity Authority, it may achieve the INDC target sooner.

Issues:

1) Domestic target versus global pledge

- No sync between the domestic target and global pledge: Several analyses have pointed out that if India achieves the 2022 target, it will likely overachieve the INDC target for next five years.

- As many of the distribution companies (discoms) are struggling with surplus capacity and storage capacities are yet to be developed, RE will add to power scheduling and balancing woes.

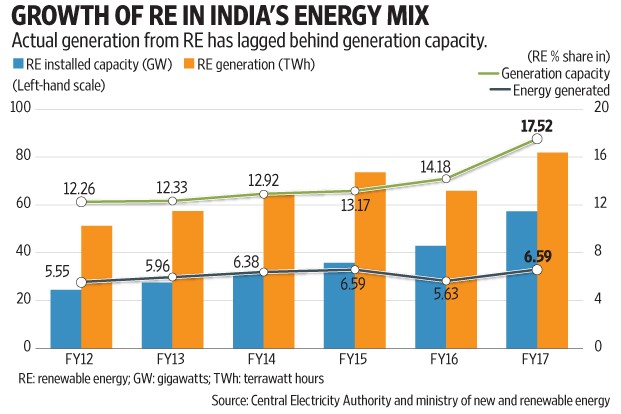

2) Mismatch between RE capacity and energy generated:

- Actual generation from proposed RE capacity is unclear due to uncertainties in capacity utilization factor. In 2016-17, with 17.52% share of generation capacity, RE contributed only 6.59% of energy generated. Part of this is blamed on reluctant evacuation by unwilling discoms, who have already contracted for higher amount of conventional power than their existing demand.

- Similarly, 33% fossil fuel-free capacity contributed less than 20% of the energy generated. Even if India achieves its INDC target, given its reliance on RE, the share of fossil fuel-free energy generated will not change much.

Source: http://www.livemint.com/r/LiveMint/Period2/2017/06/14/Photos/Processed/w_oped.jpg

3) Focus on building a domestic reform coalition is inadequate:

- Past experiences in India suggest Centre-pushed reforms have failed to sustain, owing to poor sub-national adoption.

- Sustaining the desired energy transformation needs alignment of interests and building a reform coalition between the Centre, states, utilities, regulators and private players, among others.

- On the deployment front, while there is good progress in reaching the 60 GW utility scale solar capacity, rooftop solar is lagging behind. As of April, only 1.5 GW capacity has been installed against a target of 40 GW by 2022.

4) Conventional power suppliers will be affected:

- The rise in cheap supply from renewable sources would affect the demand from conventional power suppliers in India. A hit in revenue will hurt the ability of thermal power companies to repay loans, which would mean more trouble for the banking sector.

- The fall in tariffs(solar power) may make adjustments difficult for conventional power producers

5) MNRE’s singular focus on solar energy in the renewables mission:

India is the fourth largest producer of wind energy in the world, with a total installed capacity of 27GW. Since wind power dominated the field of renewables for the longest time, the thrust for solar energy is understandable.

- However, the goal of 60GW by 2022 undermines its actual growth potential. According to National Institute of Wind Energy, India has the capacity to install and generate 302GW of wind power, as well as increase its production to 67GW by 2020 itself with the right push.

More takers of RE:

- Some states seem to be aligning with the domestic narrative of using RE for energy security and economic development, though with varying objective and approach. While states like Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh have added RE to their industrial thrust, building on the economic development narrative, states like Odisha have taken up RE to bridge energy access gap.

- Simultaneously, there is an emerging political mandate for RE. Many members of Parliament and legislative assemblies across party lines have taken up RE installation as a key part of their local area development. During recent state assembly elections, RE development featured in manifestos of many political parties.

- Government departments are being encouraged to adopt RE deployment in their activities.

- RE is allowed as a legitimate item under CSR (corporate social responsibility) spending.

Way ahead:

A high-level policy signal is in place, a political mandate is shaping up and implementing actors are coming up. To meet the global expectations, India needs much more proactive and creative actions.

- It needs to ensure that proposed RE capacity transforms the consumable energy mix. To do so, India must balance between complementing generation capacities rather than pushing for preferred technologies.

- In addition, given the unpredictability of RE generation, the time is ripe for storage capacity development.

- The proposed policy goal of electric vehicles is a welcome step, but it needs to be creatively used for storage, while reaping other co-benefits.

- Finally, the state must facilitate a domestic coalition for energy transformation, by aligning interests.

- We should prioritise the increase in shares of all renewable sources proportionately for greater reach in clean energy. Portugal and Costa Rica, for example, depend upon a renewable energy mix that affords due importance to solar, wind and hydropower, and the results speak for themselves

- Ensuring the right incentives are in place, not just for solar but all renewables, as well as strictly directing funds from the coal tax to NCFE to facilitate larger investment.

Conclusion:

With ambitious targets and policy incentives India is surely on its path of energy transformation. Globally moving towards renewable energy will help fight climate change while domestically it will help in energy security and economic development.

Connecting the dots:

- India is expected to play a major role in global energy transformation. The goals and policy incentives are in place, but more needs to be done. Discuss.

ECONOMY

TOPIC: General Studies 3

- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment.

- Effects of liberalization on the economy, changes in industrial policy and their effects on industrial growth.

Reorienting India’s trade policy

It is vital that India’s trade policy, while taking cognizance of GST’s nitty-gritties, also realigns domestic trade infrastructure with the altering global trade landscape. India’s commerce ministry is conducting a mid-year review of its trade policy to closely align it with the roll-out of the goods and services tax (GST) on 1 July. It might make more sense to re-anchor the policy in the shifting framework for global trade and the rapidly evolving nature of globalization.

Altering global trade landscape:

- Deep resentment against globalization’s misaligned distribution effects, a widening wage gap and increasing inequality have given birth to an aggressive brand of nationalism.

- Brexit in the UK, US President Donald Trump’s executive decisions on trade (withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, restricting H1B visas, threatening the North America Free Trade Agreement) or geopolitical moves (hectoring European leaders or abandoning the Paris climate change agreement) were custom-built to address localized grievances.

- Australia, New Zealand and Singapore are also following in the US’ footsteps, complicating India’s traditional trade matrix.

- Belt-Road initiative, a vehicle designed to rejuvenate China’s surplus domestic capacity and to give expression to its expansionist aspirations.

- The second is the recent schism in the Gulf with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Libya, Yemen and the Maldives collectively imposing informal sanctions against Qatar by shutting down transport links and choking essential supplies.

Way forward:

Three areas demand trade policy’s attention.

1) Targeting alternative markets:

- Less reliance on traditional trade partners in the West while increasing India’s trade and investment footprint in alternative markets, such as the African continent.

- India started looking at Africa seriously after the launch of economic reforms in 1991 and then with renewed vigour after the 2008 crisis. However, promises to increase two-way trade between India and Africa to $90 billion by 2015 have remained largely unfulfilled. India’s trade with Africa touched $56.7 billion during 2015-16, down from $72 billion in 2014-15. The drop is largely due to the fall in oil prices, which contracted India’s import bill with Nigeria. Meanwhile, China-Africa two-way trade touched $215 billion during calendar 2014.

- India has intensified its relationship with Africa, which includes initiating several high-level visits since 2015. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, President Pranab Mukherjee and vice-president Hamid Ansari have between them visited 16 countries, with senior cabinet ministers visiting the remaining countries on the continent. During May, the African Development Bank held its 52nd annual meeting in Ahmedabad.

- More needs to be done, of course. Trade policy can examine how coordinated action between commerce, finance and external affairs ministries might help in expanding India’s trade efforts; for example, a larger presence of Indian banks outside the conventional East African can help reduce export credit costs.

2) Linking India’s trade policy with Make in India:

- Second, there is a need for a clear link between India’s trade policy and Make In India, including strategic linkages through global value chains. Policy clarity will be required whether India desires domestic manufacturing platforms that double as supply hubs for a global market, or assembly units that can be folded up and relocated elsewhere when cost arbitrage dries up (Chinese mobile units are perhaps a good example). Trade policy may be able to play a role here.

3) Focusing on trade in services:

- Finally, there is trade in services. There seems to be a concerted move within the rich countries—through the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development—to open up trade in services, including movement of professionals. This has been India’s longstanding demand because trade in services has been asymmetric so far—high in capital flows, information and communication technology, but low in free movement of professionals.

- Rising unemployment, particularly in Europe, could be driving Western agencies to prise open employment markets elsewhere. India’s demand (and strategy) for trade facilitation in services should find some articulation in the revised trade policy.

Conclusion:

Recent developments are bound to reorder the global trade system. Therefore, it is imperative that India’s trade policy also realigns domestic trade infrastructure with the altering global trade landscape. It is also perhaps the perfect opportunity for the policy to be more of a strategy document rather than a manual.

Connecting the dots:

- India’s trade policy must be re-oriented asper the recent developments, both domestic as well as global. Discuss.

MUST READ

The best times, the worst times

Waiting for reconciliation in Myanmar

Moroccan Spring

Detecting possibilities

Error of commission

Language matters

Not worth the tax

The Indian Navy’s humanitarian impulse

Reorienting India’s trade policy

Why India should set store its FTA with Europe

Rushing to get last mile delivery right

China is Nepal’s new best friend