IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs July 2017, IASbaba's Daily News Analysis, Indian Heritage & Culture, National, UPSC

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 21st July 2017

Archives

INDIAN HERITAGE AND CULTURE

TOPIC:

General studies 1:

- Indian culture will cover the salient aspects of Art Forms, Literature and Architecture from ancient to modern times.

- Salient features of Indian Society, Diversity of India.

General studies 2:

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

Heritage and Culture: Do we need development at any cost? Should urbanisation score over conservation?

Introduction:

As per Ancient Monument Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act 1958, an area of 100 mtrs from protected boundary has been declared as prohibited area and an area of 200 mtrs further beyond prohibited limit has been declared as regulated area, in which construction activities are regulated.

Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and National Monuments’ Authority (NMA), technical arms of the Ministry of Culture (MoC), have the mandate to regulate construction and threats within and around protected heritage sites.

However, a recent note of the culture ministry to the cabinet has a proposal to amend the law that accords protection to heritage sites in the country.

Amendments suggested to AMASR Act, 2010

Ministry of Culture’s note suggests following amendments to the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Amendments and Validation) Act, 2010:

- It suggests giving legal powers to the Central government with respect to new construction in protected sites by superceding existing bodies like the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and National Monuments’ Authority (NMA) respectively.

- In other words, the amendments suggested tends to do away with the prohibited zones around protected national monuments whenever it chooses to do so for some supposed “public” purpose.

If above amendment or suggestion is implemented, several new constructions could happen in the immediate vicinity of protected properties of national importance.

However, the government had announced that such restrictions on new construction within the “prohibited area” adversely impact various public works and developmental projects of the Central Government. This amendment will thus pave the way for certain constructions, limited strictly to public works and projects essential to the people, within the prohibited area and benefit the public at large.

Why this proposed amendment is considered to dilute AMASR Act?

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been extremely keen to promote Indian culture as a virtuous lifestyle both within the country and abroad. Ancient Indian traditions of Yoga and Ayurveda are being pushed by the Government. Modi’s gifts to foreign dignitaries are often thoughtful symbols of historical events and the crafts of India. It therefore comes as a shock, that the same Government that deservedly places such a high value on our ancient and profound heritage, has proposed a dilution of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (AMASR Act) of 1958 to allow large-scale construction in the vicinity of nationally protected monuments.

The AMASR Act, 2010 and its 1958 predecessor can be traced to a colonial legislation, namely the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act, 1904, which deemed it “expedient to provide for the preservation of Ancient Monuments”. The blanket rule on the “prohibited areas” should, and has, been debated at various professional and academic fora. Certainly a law originating from a colonial outlook needs review, given our current depth of knowledge on heritage. However, doing away with protection without survey and documentation, can be catastrophic.

Historic structures and archaeological remains are most susceptible to heavy vibrations, chemical effects or mechanical stresses in this zone.

Importance of protecting our Heritage

- Built heritage is a ‘significant public good’ and is recognised as such in the Constitution’s Seventh Schedule.

- It nurtures our collective memories of places and is a significant constituent in the identity of cities.

- It has invaluable potential to contribute to our knowledge of not just history and the arts, but also science and technology.

- Several buildings and sites throughout the country, even entire areas or parts of historic cities, are examples of sustainable development. They demonstrate complex connections of man with nature.

Unlike other intangible forms of cultural inheritance, our built heritage is an irreplaceable resource. It is site-specific. Knowledge gained from such resources can provide constructive ways to address development challenges.

But the persistent oversight of the values of our heritage is one of the major paradoxes of physical planning and urban development in post-colonial India. Conservation of heritage is not seen as a priority to human need and development. Heritage sites are more often than not seen as consumables and usually end up as the tourism industry’s cash cows and little else.

The rationale behind restrictions

Unfortunately, most of our 3686 nationally protected monuments, some of which are absolutely unique in the world, are not in great shape. They suffer not only from neglect and gradual disrepair, but sadly are also being encroached upon, ruining the ambience and aesthetics of these magnificent structures.

In Hyderabad for example, unauthorised structures and encroachments have sprung up at and around historic monuments in the city, such as Golconda Fort, Charminar and Qutb Shahi Tombs, leading the state government to consider a special task force to clear these and seek UNESCO recognition for the monuments.

The direct amendment of law by the government without any consideration of such carefully planned and sustainable alternatives, raises certain questions.

- What is the value we place on the environment and our built and natural heritage?

- What is the value of the lives of the poor and marginalized (the tribals)?

- Do we want development at any cost, even at the cost of those who cannot speak or stand up for themselves?

- Many of these monuments have stood the test of time, but will they succumb now to mindless human activity?

Conclusion:

It is really up to us as a nation and as a society to decide. All those interested in the defence of our heritage must do their best to oppose this proposal.

It must be kept in mind that any construction, whether for a public project or private purpose, will pose risks to a monument. Allowing an exception for “public works” will open a Pandora’s Box, and it will be all but impossible for the National Monuments Authority or the Archaeological Survey of India to ensure that such construction do not pose a threat to a monument.

Public works are more often than not very large infrastructure projects. Allowing these in the immediate vicinity of a protected monument will defeat the very purpose of the AMASR Act and will be a violation of Article 49 of the Constitution.

Connecting the dots:

- Conservation of heritage is not seen as a priority to human need and development. Examine the statement in the light of the recent controversy with Ministry of Culture’s proposal to amend the law that accords protection to heritage sites in the country.

- The government has approved changes to the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act, 1958. What are these changes? What will be their implications? Examine.

- Critically analyze why the recently proposed amendments to “Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958” are considered to be diluting and hurting India’s heritage.

NATIONAL

TOPIC:

General Studies 3:

- Issues related to direct and indirect farm subsidies and minimum support prices

- Inclusive growth and issues arising from it.

General Studies 2:

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

- Welfare schemes for vulnerable sections of the population by the Centre and States and the performance of these schemes; mechanisms, laws, institutions and bodies constituted for the protection and betterment of these vulnerable sections

Agrarian Crisis: Root cause and week ahead

Background:

In the last 20 years, according to the government’s statistics, more than three lakh farmers have committed suicide in India. The situation of the farmers was never very good to begin with, but has been steadily declining and has reached its nadir right now. Earlier spontaneous agitations by farmers are getting organised and now, a coordinated all-India farmers’ movement is beginning to take shape which promises to be the beginning of one of the most significant farmers’ movement in the history of this country.

Root causes of agrarian crisis:

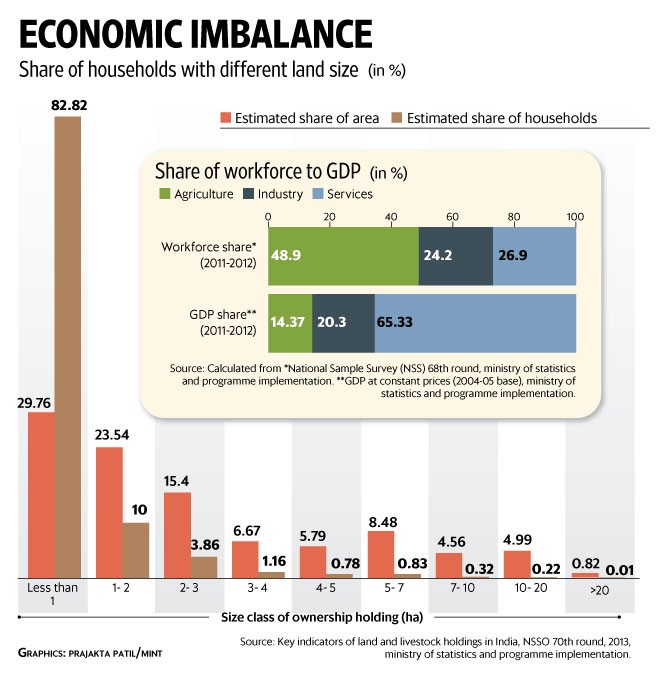

- The intense pressure of population on land.

Demographic pressure has pushed down the land: man ratio to less than 0.2 hectares of cultivable land per head of rural population. It has also progressively pushed down the size structure of landholdings. Around 83% of rural households are either entirely landless or own less than 1 hectare of land. Another 14% own less than 3 hectares.

The burgeoning growth of landless or marginal farmer households is the consequence of decades of land fragmentation as family plots are divided and passed on from one generation to the next, especially male children.

- The shortage of money.

Landless or marginal farmers lack the resources to either buy or lease more land or invest in farm infrastructure—irrigation, power, farm machinery, etc.—to compensate for the scarcity of land. As land scarcity intensifies with population growth, farming progressively becomes a less viable source of livelihood.

Despite subsidies on power, fertilizers, etc., input costs have been rising faster than sale prices, further squeezing the meagre income of the small farmers and driving them into debt. About 52% of agricultural households are estimated to be in debt, and the average size of household debt is Rs47,000. If small farmers are subjected to any of the production or marketing shocks, it knocks the bottom out of their precarious existence. There is a strong correlation between crop failure and the incidence of farmer suicides

- The barrage of risks to which a farmer is constantly exposed.

The first risk is the weather. The large majority of small farmers are dependent on the rains. A weak monsoon or even a delayed monsoon—timing matters—means a significant loss of output. Aggravated by the fact that rain-fed agriculture accounts for two-thirds of India’s total cultivable area.

The next risk is weak soil fertility, pests and plant diseases.

The third risk is price. Even a good harvest can be bad news for the small farmer, placing him at the mercy of the trader. The better the crop the lower would be the price. Net income sometimes collapses if there is a very good crop of perishables. The highly distorted and exploitative product market is a major factor responsible for the misery of the small farmer.

- Green revolution: as root cause of crisis

The Green Revolution led agriculture towards chemical fertilisers, pesticides, irrigation through large dams and massive irrigation projects.

- With chemical fertilisers and hybrid seeds came the problems of resistance in pests and that led to the wider use of pesticides and also of higher potency.

- This infused poison in the food — especially for farmers, who also inhale the pesticides and, therefore, the higher incidence of cancer and other diseases.

- The chemical fertilisers added only a few chemicals like nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus to the soil without replenishing it with micro-nutrients and the pesticides kill even the soil bacteria. Eventually, the productivity started coming down and with greater use of pesticides, the input cost began to increase.

- Simultaneously, canals and canal irrigation led to water-logging and a substantial part of the land became wasteland. In areas which were not irrigated by canals, there was a rise in the unregulated and unsustainable usage of tubewells to mine groundwater, leading its levels to fall rapidly. This led to even deeper tubewells, adding once again to the input costs for the farmers.

Issues with MSP:

- For food grains like rice and wheat, government procurement at the minimum support price is supposed to protect the farmer. But it mainly benefits the large traders who sell grain to the government.

- Small farmers typically do not have enough marketable surplus to justify the cost of transporting the crop to government corporations in the towns. Their crop is usually sold to traders at rock bottom post-harvest prices in the village itself or the nearest mandi.

- Also the government has fixed minimum support prices (MSP) for just wheat and rice, not for other crops.

- The MSP so fixed is just about adequate for farmers to meet their costs without giving even minimum wages for their own labour.

- In the case of other crops, Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), which were supposed to protect the farmer, have had the opposite effect. Farmers have to sell their produce through auctions in regulated markets controlled by cartels of licensed traders, whose licences give them oligopolistic market power. These cartels fix low purchase prices, extract large commissions, delay payments, etc.

Solving the agrarian crisis:

Cooperative farming:

Increasing land scarcity and the marginalization of farmers cannot be easily reversed. But cooperative farming can help contain the adverse consequences of such marginalization.

There are several variants of cooperation ranging from collective action in accessing credit, acquiring inputs and marketing to production cooperatives that also include land pooling; labour pooling; joint investment, joint water management and joint production.

The advantages of aggregating small farms into larger, voluntary, cooperatives include:

- Greater capacity to undertake lumpy investment in irrigation and farm machinery.

- More efficient farming practices.

- Greater bargaining power and better terms in the purchase or leasing of land, access to credit, purchase of inputs and the sale of produce.

The cooperative approach also has its problems, such as internal conflict, free riding, etc., but farming communities have also found institutional solutions to these problems.

The conditions for success of such cooperative approaches include voluntariness, cooperative units of small groups, relative socioeconomic homogeneity of cooperating households, transparent and participatory decision-making, checks and penalties against free riding, and group control over the fair distribution of returns.

Successful cooperatives in past:

- The Amul milk cooperative in Gujarat.

- The Kudumbashree programme in Kerala.

- The Society for Elimination of Rural Poverty programme in Andhra Pradesh.

Learning from Kudambshree programme:

The key feature of programme was that it was women-led initiative founded on a base of voluntary women’s self-help groups (SHGs). These are aggregated through structures of democratic representation into higher-level associations. While it is closely linked to accessing credit, they have extended into many activities, including land pooling, organic agriculture, dairy, fishery, marketing and even non-farm activities such as insurance, auditing, entrepreneur incubation and training.

While the state government has played a key role in nurturing the programme from the beginning, with assistance from multilateral agencies, an essential aspect is that it is the SHGs, not the governments, which are in control.

It has emphasized the need for state governments to maintain a flexible approach, adjusted to ground conditions in each state, and the need for them to reach out to local voluntary institutions without seeking to control them if the SHG-based approach is to be successfully replicated in other states.

The Swaminathan Commission recommendations needs to be implemented:

The committee had gone into this issue of MSP and had recommended that it should be extended to all crops and should be at least 50 per cent above the average cost price of farmers in each state.

Organic farming:

If farmers are to be rescued from this crisis we desperately need to change the whole agriculture policy. Move towards organic farming, irrigation by rain-water harvesting and micro-water irrigation, shifting from chemical to organic fertilisers, which will also use less pesticides.

Conclusion:

In India, 50 per cent of the people are still dependent, directly or indirectly, on farming. Though agriculture now accounts for less than 15% of gross domestic product (GDP), it is still the main source of livelihood for nearly half our population. We cannot ignore their plight anymore. Agriculture is still the core of our food security. With over 1.3 billion mouths to feed, imports will not solve our problem if there is a severe drought and food shortage.

Connecting the dots:

- With farmers’ agitations and suicide on rise, India is surely facing an agrarian crisis. Discuss the root cause of the crisis. Also elaborate on what changes should be made in our agricultural policy so as to improve the livelihood of farmers as well as to ensure food security.

MUST READ

Gain in translation

The new President

Re-arming the law

Heed the warning

Taxing Body Parts

Healthcare systems need drastic surgery