IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 11th Nov 2017

Archives

ECONOMY

TOPIC:General Studies 3

- Economic Development – Indian Economy and Issues relating to growth and development – Different indicators used to measure growth

Social Progress Index: An index import for balanced development

Is Gross Domestic Product (GDP) an adequate measure of a country’s development across many dimensions?

- The GDP calculation focusses exclusively on economic growth.

- Even while focusing on economic growth, it does not capture the level of inequity which can exist in a society despite overall economic growth. The inequity can in fact even be exacerbated by it.

- It pays no attention to the social and environmental measures of development which are as important as economic development.

- The most significant weakness of GDP is its exclusion of voluntary market transactions. GDP as a measure of economic growth fails to account for productive non-market activities, like a mother taking care of her child, a homemaker doing household chores, a homeowner doing maintenance of his house, leisure (paid vacation, holidays, leave time), improvement in product quality, etc.

- GDP also ignores important factors like environment, happiness, community, fairness and justice.

Alternate measures and their limitations:

Several alternative measures have been proposed to capture the social dimension of development, combined with or independent of economic indices.

- Gross National Happiness, which was introduced in the 1970s by the king of Bhutan, measures the happiness levels of the citizens in a country while it ignores other important elements like gender equality, quality education and good infrastructure.

- A World Happiness Report is now periodically published from the Columbia University which compares self-reported levels of happiness of people from different countries.

- A composite Wellness Index was proposed by noted economists Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi, for a measure of development that looks beyond GDP.

- A Global Multidimensional Poverty Index was developed at Oxford to gauge inequity within and across societies.

- GINI coefficient which was introduced in 1912 by Corrado Gini and adopted by World Bank, and measures the income inequality among a country’s citizens — fails to measure social benefits or interventions that reduce the gap or inequality between rich and poor.

- Human Development Index, devised and launched in 1990 by Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq, is computed and published by the United Nations Development Programme and overcomes most of the shortcomings of the Gini coefficient and GNH.

However, HDI, as a measure, falls short in its capture of the unequal distribution of wealth within the country and the level of infrastructural development.

Many prospects of a healthy society, such as environmental sustainability and personal rights, are not included in HDI.

The need of Social Progress Index:

- An index of social progress is needed which do not try to displace GDP but has additive value.

- Such an index can be used to remind political leaders that their vision must accommodate both economic and social progress as being important for a country, recognising, of course, that these two tracks are closely interlinked and sometimes inseparable.

About SPI:

The SPI was launched in 2013 and is based on 52 indicators of countries’ social and environmental performance. It includes no economic indicators and measures outcomes.

it has been created by a group of academics and institutions constituting the Social Progress Imperative (www.socialprogressimperative.org).

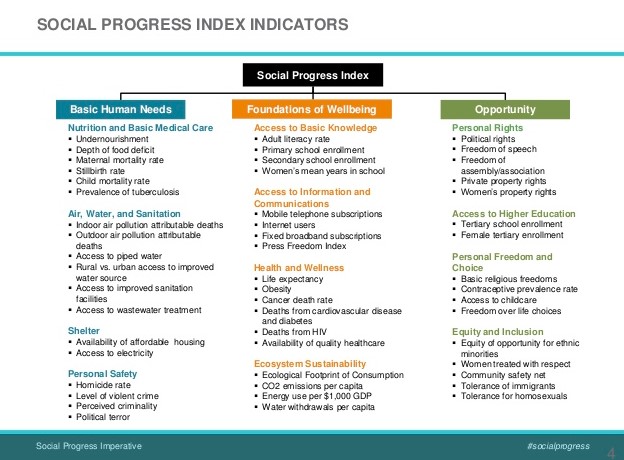

This index has three major domains:

1) Basic Human Needs.

2) Foundations of Wellbeing.

3) Opportunity.

Each of these has several clusters of specific indicators (as shown below).

Pic credit: https://www.slideshare.net/socprog/20130411-skoll-world-forum-panel-final

Pros of SPI:

- The index offers a new tool to explore the complex two-way relationship between economic and social progress.

- It provides a metric for comparison of countries, and States within a country.

- The SPI indicators can serve as a checklist to monitor our progress over time in each of the important areas of human welfare.

State level:

The study (2005-2016) helps analyze whether States, especially using social and environmental indicators, are heading in the right direction. It is also essential to help adjust policies as well as public and private investments.

States can be ranked using social and environmental indicators on the basis of:

- Their capability to provide for basic needs such as shelter, water, and sanitation.

- A foundation for well-being with education, health, and communication facilities.

- Analysing the prejudices that prevail in a region prohibiting people from making their personal decisions; and

- Evaluating whether citizens have personal rights and freedom or whether they are susceptible to child labour, human trafficking, corruption, etc.

Major findings of the Social Progress report, 2017:

- The overall social progress score for the country now stands at 57.03 (on a 0-100 scale), approximately eight points higher than in 2005.

- The country performs better in the provision of basic human needs rather than opportunities for its citizens. Therefore, creation of a society with equal opportunities for all still remains an elusive dream.

- The scores for opportunity have increased over the years followed by smaller, but important improvements in the areas of basic human needs and foundations of well-being.

- All the States have climbed the social progress ladder, with the group of States that had the worst performance in 2005 — Tripura, Meghalaya, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Bihar — now showing improvement.

This suggests that States with a relatively low level of social progress can improve rapidly. - The greatest improvements have been in areas where social progress most often accompanies economic prosperity. On the other hand, areas where performance has declined or stagnated is where the correlation with economic development is weak.

For instance, “Access to Information & Communication and Inclusion” depicts a strong relationship with per capita GDP and are the ones that have improved the most over the years. And “Health and Wellness & Environmental Quality”, that are least correlated with economic development, have eroded. - One significant difference between GDP and SPI is that SPI focusses on outcomes rather than inputs that are used in GDP.

For example, the quality of life and longevity are measured instead of spending on health care, and people’s experience of discrimination is looked at instead of focussing on whether there is a law against discrimination. SPI also reframes the fundamentals about development by taking into consideration not just GDP but also inclusive, sustainable growth that will lead to a significant improvement in people’s lives. SPI can best be described as a complementary index to GDP and can be used along with GDP to achieve social progress.

Policies need to target social issues directly:

- The States should focus on policies that target social issues. The focus on economic parameters will result in unbalanced social development.

- The overall findings show that while the economy is on the right track, there is an urgent need to identify and focus on social parameters. The reliance on the idea that economic development will automatically transform social conditions will hamper further improvements in social progress.

Social progress needs to be stimulated by focusing on policies directly targeting social issues.

Summary:

In conclusion, SPI can bring substantial betterment in the policy discourse on development. With the move to getting it introduced at a sub-national level, the index is expected to help development practitioners and other stakeholders in analysing well-being in a better manner.

Focusing exclusively on GDP implies measuring progress in purely monetary terms and failing to consider the wider picture of the real things that matter to real people. GDP isn’t bad but it’s not the whole story, alongside economic growth social progress is more important for policymaking. Even as India commits itself to move on the fast track of economic growth, it must be mindful of the need to invest in improving its social indicators as well

MUST READ

Hope floats on a boat

Asian disorder

The witch hunters

Affordable housing- a costly affair

Course correction