UPSC Articles

POLITY/ JUDICIARY

- GS-1: Fundamental Freedoms & Restrictions

- GS-2: Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation

Monoculture in Punjab

Context: Amidst the ongoing farmers’ protests are also questions that are being raised on the sustainability of paddy-wheat cultivation, especially in Punjab.

What is the extent of paddy-wheat monoculture in Punjab?

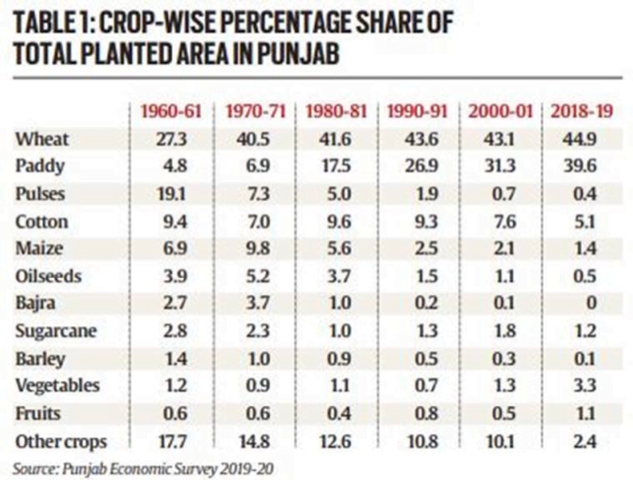

- Punjab’s gross cropped area in 2018-19 was estimated at 78.30 lakh hectares (lh).

- Out of that, 35.20 lh was sown under wheat and another 31.03 lh under paddy, adding up to 84.6% of the total area planted to all crops.

- That ratio was just over 32% in 1960-61 and 47.4% in 1970-71.

- This has been at the expense of pulses (after 1960-61), maize, bajra and oilseeds (after 1970-71) and cotton (after 1990-91)

- Wheat replaced chana, masur, mustard and sunflower, while cotton, maize, groundnut and sugarcane area got diverted to paddy.

- The only crops that have registered some acreage expansions are vegetables (especially potato and pea) and fruits (kinnow), but they hardly amount to any diversification

Why is monoculture such a problem?

- Growing the same crops year after year on the same land increases vulnerability to pest and disease attacks.

- The more the crop and genetic diversity, the more difficult it is for insects and pathogens to infect.

- Wheat and paddy cannot also, unlike pulses and legumes, fix nitrogen from the atmosphere.

- Their continuous cultivation without any crop rotation, then, leads to depletion of soil nutrients. As a result, crops will have to increasingly depend on chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

- In Punjab’s case, the issue isn’t as much with wheat, which is naturally adapted to its soil and agro-climatic conditions.

- Wheat is a cool season crop that can be grown only in regions – particularly north of the Vindhyas – where day temperatures are within early 30oC range through March (temperature sensitive)

- Its cultivation in Punjab is also desirable from a national food security standpoint.

- Punjab’s wheat yields – at 5 tonnes-plus per hectare, as against the national average of 3.4-3.5 tonnes – are far too high to make any reduction in its cultivation area.

So, it is basically paddy that needs fixing?

Yes, there are two reasons for it.

- The first has to do with paddy being a warm season crop not very sensitive to high temperature stress. It can be grown in much of eastern, central and southern India, where water is sufficiently available.

- Punjab contributed 10.88 mt of rice (milled paddy) out of total Central pool procurement of 52 mt in 2019-20. Probably half of this rice of Punjab can, instead, be procured from eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal or Assam.

- The second has to do with water usage. Farmers usually irrigate wheat five times. In paddy, 30 irrigations or more are given.

- Punjab’s groundwater table has been declining by 0.5 m/annum on an average – largely due to paddy cultivation and the state’s policy of supplying free power for irrigation.

- This has encouraged farmers to grow long-duration (160 days) water-guzzling paddy varieties like Pusa-44.

- Long duration meant that nursery-raising happened in April last week and transplanting by mid-May. But being peak summer time, it also translated into very high water requirement.

- Crops were then harvested from October leaving ample time for planting of the next wheat crop (by mid-November).

- Before Pusa-44’s release in 1993, Punjab farmers were mostly cultivating PR-106, which required less water and was short duration(145 days).

Has the Punjab government done anything to address this?

- The one significant step that it took was enacting the Punjab Preservation of Subsoil Water Act in 2009, that prohibited any nursery-sowing and transplanting of paddy before May 15 and June 15, respectively.

- Therefore, transplanting of Pusa-44 was permitted only after the monsoon rains arrived in mid-June. This was done to address the water requirements.

- As a result, harvesting was pushed to October-end, leaving a narrow time window for sowing wheat before the November 15 deadline.

- Farmers, then, had no option other than burning the paddy stubble left behind after harvesting.

- Simply put, groundwater conservation in Punjab ended up causing air pollution in Delhi.

Has there been any way to avoid this trade-off?

- One thing that scientists at the Punjab Agriculture University (PAU), Ludhiana have done is breed shorter-duration paddy varieties. These take between 13 and 37 days less time to mature than Pusa-44, while yielding almost the same (see table 2).

- PR-126, a variety released in 2017, has a mere 123 days duration (inclusive of 30 days post nursery-raising) and its yield is 30 quintals per acre.

- In 2012, 39% of Punjab’s non-basmati paddy area was under Pusa-44. That was down to 20% in 2021, while the share of shorter-duration varieties, mainly PR-121 and PR-126, has crossed 71%.

- While Pusa-44 requires around 31 irrigations, it is only 23 in PR-126 and 26 in PR-121. There would be further 3-4 irrigation savings if farmers adopt direct seeding of paddy, as opposed to transplanting in flooded fields.

- A single irrigation consumes roughly 2 lakh litres of water per acre.

Way forward

- A sensible strategy could be to limit Punjab’s paddy area and ensure planting of only shorter-duration varieties.

- Further water savings can be induced through metering of electricity and direct seeding of paddy.

Connecting the dots: