Social Issues

Context: India is currently facing a unique job crisis because, while fewer people are employed in agriculture today, the transformation has been slow.

Stats

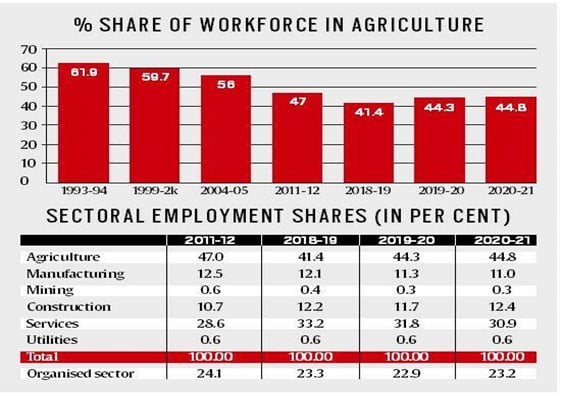

- Between 1993-94 and 2018-19, agriculture’s share in India’s workforce came down from 61.9% to 41.4%, roughly a third in 25 years.

- Given its level of per capita GDP in 2018 – and comparing with the average for other countries in the same income bracket – India’s farm sector should be employing 33-34% of the total workforce.

- 4% may not be a substantial deviation from the average.

Weak structural transformation

- There’s been a reversal of the trend in the last two years, which has seen the share of those employed in farms rise to 44-45%. This has primarily to do with the Covid-induced economic disruptions.

- Even the movement of workforce from agriculture that India has witnessed over the past three decades or more does not qualify as what economists call “structural transformation”.

- Such transformation would involve the transfer of labour from farming to sectors –manufacturing and modern services – where productivity, value-addition and average incomes are higher.

- The share of manufacturing (and mining) in total employment has actually fallen along with that of agriculture.

- The surplus labour pulled out from the farms is being largely absorbed in construction and services.

- While the services sector does include relatively well-paying industries — such as information technology, business process outsourcing, telecommunications, finance, healthcare, education and public administration — the bulk of the jobs in this case are in petty retailing, small eateries, domestic help, sanitation, security staffing, transport and similar other informal economic activities.

- Simply put, the structural transformation process in India has been weak and deficient.

- The surplus labour isn’t moving to higher value-added non-farm activities, specifically manufacturing and modern services (the familiar ‘Kuznets Process’ named after the American economist and 1971 Nobel Memorial Prize winner, Simon Kuznets).

- Instead, the labour transfer is happening within the low-productivity informal economy.

- The jobs that are getting generated outside agriculture are mostly in low-paid services and construction; the latter’s share in employment has even overtaken that of manufacturing.

- Weak structural transformation and persistence of informality also explains the tendency, especially by rural families, for pursuing multiple livelihoods. Many of them cling on to their small plots of lands, even while earning incomes wholly or predominantly from non-farm sources.

A picture in contrast

IT industry adding jobs:

- The IT industry is clearly an isolated island of the Indian economy that added jobs during the pandemic and is continuing to do so.

- The five companies (Tata Consultancy Services, Infosys, Wipro, HCL Technologies and Tech Mahindra) have more employees than the 12.5 lakh and 14.1 lakh currently on the rolls of the Indian Railways and the three defense services, respectively.

- Much of the IT sector’s recent success is courtesy of exports.

- These have, in fact, boomed due to Covid’s triggering increased demand for digitisation even among businesses that were hitherto slow in adoption.

- India’s net exports of software services have surged from $84.64 billion in 2019-20 to $109.54 billion in 2021-22.

India’s unique job crisis

- The manufacturing sector is potentially best placed to absorb agricultural labourers. However, there is a lack of jobs in the manufacturing sector.

- The more educated are not qualified to be programmers or develop software programs which are essential for the IT industry.

- They aim to join the armed forces or to sit for the Railway Recruitment Board’s exams.

- However, there is not much recruitment in these sectors these days.

So, the Indian workforce possesses skill sets for the sectors where there is a lack of job opportunities. And sectors that generate excess jobs require particular skill sets that the majority of the Indian workforce lacks.

As a result, the Indian economy is unable to absorb excess labour.

Source: Indian Express