Social Issues

Context:

- Several top Haryana-based World and Olympic medallist wrestlers, including Vinesh Phogat, Bajrang Punia and Sakshi Malik, began a protest in Delhi, alleging sexual harassment of young wrestlers by Mr. Singh and financial misappropriation by the WFI.

- Union Sports Minister announced that six-time World champion and Olympic medallist boxer M.C. Mary Kom will head a government-appointed five-member Oversight Committee (IOA panel) to investigate the charges levelled by some prominent wrestlers against Wrestling Federation of India (WFI) president Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh.

Definition of Sexual harassment

- As per Sexual Harassment of Women in the Workplace Act 2013, “sexual harassment” includes any one or more of the following unwelcome acts or behaviour

- physical contact and advances; or

- a demand or request for sexual favours; or

- making sexually coloured remarks; or

- showing pornography; or

- any other unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct of sexual nature;

- Additionally, the Act mentions five circumstances that amount to sexual harassment —promise of preferential treatment in her employment, threat of detrimental treatment, threat about her present or future employment status, interference with her work or creating an offensive or hostile work environment and humiliating treatment likely to affect her health or safety.

Vishaka guidelines

- These were laid down by the Supreme Court in a judgment in 1997.

- This was on a case filed by women’s rights groups, one of which was Vishaka.

- They had filed a public interest litigation over the alleged gang-rape of Bhanwari Devi, a social worker from Rajasthan.

- In 1992, she had prevented the marriage of a one-year-old girl, leading to the alleged gang-rape in an act of revenge.

- Legally binding, these defined sexual harassment and imposed three key obligations on institutions — prohibition, prevention, redress.

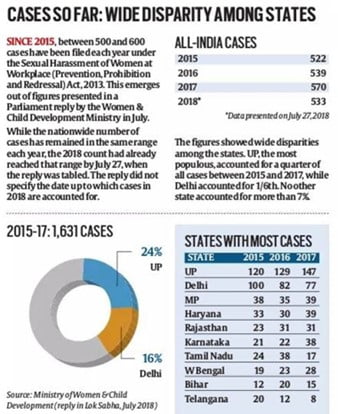

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act

- It was passed in 2013.

- It defines sexual harassment, lays down the procedures for a complaint and inquiry, and the action to be taken.

- It broadens the Vishaka guidelines as follows:

- It mandates that every employer constitute an Internal Complaints Committee (ICC) at each office or branch with 10 or more employees.

- It lays down procedures and defines various aspects of sexual harassment, including aggrieved victim — a woman “of any age whether employed or not”, who “alleges to have been subjected to any act of sexual harassment”, which means the rights of all women working or visiting any workplace, in any capacity, are protected under the Act.

Procedure for complaint

- The Act says the aggrieved victim “may” make, in writing, a complaint of sexual harassment.

- If she cannot, any member of the ICC “shall” render “all reasonable assistance” to her for making the complaint in writing.

- The complaint of sexual harassment has to be made “within three months from the date of the incident

- Section 10 of the Act deals with conciliation – The ICC “may”, before inquiry, and “at the request of the aggrieved woman, take steps to settle the matter between her and the respondent though conciliation” — provided that “no monetary settlement shall be made as a basis of conciliation”.

- After the recommendations, the aggrieved woman or the respondent can appeal in court within 90 days

- Section 14 of the Act deals with punishment for false or malicious complaint and false evidence. The Act, however, makes it clear, that action cannot be taken for “mere inability” to “substantiate the complaint or provide adequate proof”.

Priya Ramani case

- In February 2021, a trial court acquitted Priya Ramani in the criminal defamation case filed by her former boss and editor-turned-politician, MJ Akbar for accusing him of sexual harassment during the #MeToo movement in 2018.

- Judge Ravindra Kumar Pandey made significant observations in the judgment – the woman cannot be punished for raising voice” as the “right of reputation cannot be protected at the cost of the right of life and dignity of a woman

Suggestions for future:

- IOA panel formed to probe the allegations of sexual misconduct, harassment and intimidation, financial irregularities and administrative lapses – Mary Kom heads the IOA panel as well.

- Attitudinal shift – Organisations must take institutional responsibility for an attitudinal shift.

- Institutional accountability requires employers to institute a Complaint Mechanism and a Complaints Committee as per Vishakha guidelines, reiterating the importance of its independence by having an external member, conversant with the issue of sexual harassment.

- Role of judiciary – the Supreme Court of India in Medha Kotwal Lele and ors. Vs. Union of India recognised that “women still struggle to have their most basic rights protected at workplaces”

- The Medha Kotwal judgment accepted that a woman has reasonable grounds to believe that her objection would disadvantage her at work or create a hostile work environment.

- Regulatory framework – Sexual harassment has been brought under the ambit of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which is an important step in understanding the gravity of its impact on women.

- A significant amendment to the Indian Evidence Act of 1872, stated that where the question of consent is an issue, “evidence of the character of the victim or previous sexual experience shall not be relevant”.

- This amendment would necessitate a transformational change in how survivors are treated in court, emphasising the need to stop re-victimisation.

Way forward

- Despite these watershed moments in our legal history that demand a cultural shift in the treatment of survivors, they continue to fear for their physical safety, their job security and their mental health for rejecting an unwelcome sexual advance or reporting it.

- Evidence shows that due processes meant to protect survivors and help them access justice, leave survivors feeling betrayed.

- Shifting blame on the survivor or making veiled accusations during the inquiry process coerces them into silence and unjustifiably puts the burden of proof back on the victim.

- As Ramani expressed upon her acquittal in the defamation suit against her, that despite being a victim of sexual harassment, she had to stand in Court as the accused.

Source The Hindu