IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs March 2016, UPSC

Archives

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 15th March, 2016

ECONOMICS

TOPIC:

General studies 2:

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

General studies 3:

- Effects of liberalization on the economy, changes in industrial policy and their effects on industrial growth.

How reforms killed Indian manufacturing?

- This year marks 25 years since the so-called “economic reforms” were launched in July 1991.

- By now, broad contours of the policies and practices that characterized such reforms are well known, viz. radical deregulation, marketization and privatization of the industrial, technological and financial sectors, and an across-the-board induction of foreign direct investment and foreign institutional investment, and so on.

Promotion of India’s IT software and service sector:

- Based on the “advice” of Western governments, large foreign companies and the trinity of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organisation, the then Finance Minister, concluded around mid-1992 that we could be globally competitive only in IT software and services and not in hardware.

- Thus he reduced import duties on all IT hardware purportedly to “facilitate” software promotion and growth on a globally competitive basis using imported hardware.

- Result: by 1994 our fledgling civilian IT hardware industry folded up.

No one seems to have told the then Finance Minister that IT hardware far more technologically sophisticated than the commercial hardware being imported by our software companies was being manufactured by Indian defence, atomic energy and space agencies and even exported to other developing countries such as Brazil, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Death by policy:

A case study of Optel:

- The “reforms” also gave a body blow to the indigenous optic fibre telecommunication systems industry, a project begun by the Department of Electronics (DoE) in 1986 with the setting up of the public sector utility, Optel.

- Based on a global tender, technology-transfer agreements were concluded with two companies, Fujitsu and Furukawa, in 1987 and a blueprint for the Optel plant prepared.

- It indicated a project cost of Rs.45 crore and a construction period of 30 months; when completed, the actual numbers were Rs.46 crore and 32 months.

Performance of Optel:

- In its very first year (1989) of commercial operations Optel’s turnover was Rs.64 crore with a profit of Rs.11 crore. In 1990-91 the turnover zoomed to Rs.298 crore with Rs.35 crore profit.

What happened next?

- Around this time, Sterlite, a metallurgical company, and Finolex, a packaging material producer, entered the field.

- They would import fibres and merely sheath them into cables.

- Even the sheathing material was imported, the cables had merely 10-15 per cent domestic content.

- This, however, ran into a roadblock in the form of the graduated customs duties then applicable, which promoted local production.

- They started lobbying with the government to reduce the import duty on fibre, a manufactured component, from 40 per cent to 10 per cent, which was the duty on raw materials.

The end of Optel:

- Within six months, large quantities of optic fibre began to be imported.

- Optel had to close down its optic fibre plant and import low-grade fibre from China to be able to compete in our own market with the likes of Sterlite and Finolex!

De industrialization:

- High tech radio equipment:

- In 1990-91, there were at least a dozen electronics corporations producing a range of high-tech radio communication equipment, industrial electronics and control and instrumentation equipment worth annually around Rs.6,000 crore.

- However, the reduction in customs duties from 60 per cent to 30 per cent overall, which led to a glut of imports, forced many of these corporations to halt production and become import agents.

- Cell phone handsets:

- “Reforms” also led to large-scale import of cell-phone handsets that could have been easily produced here had a policy of phased manufacture been adopted.

- Result? The entire market for such handsets was met by unnecessary imports from Day One in 2005-06. In 2013-14 cell-phone imports totalled Rs.35,000 crore.

- Case of BHEL:

- Up until 1998-1999, our heavy electrical equipment industry led by Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL) was doing very well.

- However from the next year onwards, four Chinese power plant equipment manufacturers began to seriously erode BHEL’s market.

- This erosion was despite the quality and technical reliability of the Chinese equipment being considerably inferior to BHEL’s products.

- The United States, home to General Electric and Westinghouse, imposed penal anti-dumping duties on Chinese power plant equipment.

- Yet, the Indian government merely watched as BHEL lost 30 per cent market share by 2014.

Way ahead:

- The above examples indicate that in sector after sector, the “reforms” have led to de industrialization.

- Products that we were manufacturing in the 1990s are being imported now.

- The negative impact this de industrialization has had on employment and on our economy is gigantic.

- The government must act immediately to halt the destruction of domestic industry on such a massive.

- One such act by the government to promote domestic manufacturing industry is the “Make in India” policy.

Connecting the dots:

- Critically examine the importance of Make in India policy in reviving the domestic manufacturing sector of India.

- Economic reforms of 1991 was both a boon and bane. Critically evaluate the statement at the backdrop of low domestic manufacturing base in India.

ECONOMICS

TOPIC: General studies 3

- Infrastructure: Energy, Ports, Roads, Airports, Railways etc.

Need of the hour: Energy security, not energy independence

Background:

- In the next one and a half decade (i.e., by 2030), India’s energy demand will grow faster than that of any other country in the G-20.

- India’s share in the daily oil trade then is expected to be 12.5 per cent, up from 7.4 per cent in 2014.

- India will not be the biggest energy consumer; nor will it remain at the margins. Indeed, it will be a swing voter in global energy markets with strong national interest in well-functioning markets.

What does Energy security mean?

- Energy security would mean the availability of adequate quantities of critical resources, at prices that are affordable and predictable, with minimum risk of supply disruptions, to ensure sustainability for the environment and future generations.

- Energy security will require meeting four imperatives: assured supply, safe passage, secure storage, and a seat at one or more international forums involved in international energy trade and governance.

- Energy security is the association between national security and the availability of natural resources for energy consumption. It isthe continuity of energy supplies relative to demand.

What are the challenges to be tackled to address India’s energy security?

- Like China, India is a growing giant facing the critical challenge of meeting a rapidly increasing demand for energy.

- With over a billion people, a fifth of the world population, India ranks sixth in the world in terms of energy demand.

- India’s economy is projected to grow 7%-8% over the next two decades, and in its wake will be a substantial increase in demand for oil to fuel land, sea, and air transportation.

- While India has significant reserves of coal, it is relatively poor in oil and gas resources. Its oil reserves amount to 5.9 billion barrels, (0.5% of global reserves) with total proven, probable, and possible reserves of close to 11 billion barrels.

- The majority of India’s oil reserves are located in field’s offshore Bombay and onshore in Assam. Due to stagnating domestic crude production, India imports approximately 70% of its oil, much of it from the Middle East. Its dependence is growing rapidly.

- Ownership of assets might have a limited role in times of crisis: it has mostly been an ineffective strategy because of low shares of overseas production (below four per cent of total oil and gas demand in 2014-15), a lack of financial resources to compete with other countries, the risks of operating in politically fragile areas, and the opportunity cost of not selling energy produced in global markets.

- The World Energy Outlook, published by the International Energy Agency (IEA), projects that India’s dependence on oil imports will grow to 91.6% by the year 2020.

- The Indian government is deeply concerned about the rising share of crude oil imports, from 65 per cent of oil demand in 2000, to 83 per cent in 2013-14 and to 90 per cent in 2030.

- Coal imports have been rising year on year, reaching over 20 per cent of demand. By 2030, imports of natural gas are likely to rise to five times the level in 2013-14.

What are the threats to energy security?

- Political instability of several energy producing countries

- Manipulation of energy supplies

- Competition over energy sources

- Attacks on supply infrastructure as well as accidents

- Natural disasters

- Terrorism and reliance on foreign countries for oil.

What are the strategies employed to secure energy security?

- The first is to aspire to energy independence. This does not imply zero imports but aims to reduce rather than increase the share of imported oil, gas and coal. For instance, the government wants oil imports to fall to 67 per cent of demand by 2022 and to 50 per cent by 2030.

- The second strategy has been to buy acreages in oil and gas fields and in coalmines beyond India’s shores. The assumption is that such overseas assets will deliver energy resources to India’s shores in times of crisis.

Way ahead:

India’s diplomatic capacity has to align with its commercial interests, while the economy shifts from long-term contracts to relying on diverse sources, taking advantage of lower spot market prices and hedging via forward contracts.

India will need to ensure safe passage of overseas energy supplies:

- This will be, partly, a function of India’s ownership of – or access to – a shipping fleet. Compared to other major energy consumers, India’s share of oil and gas tankers is low.

- Safe passage will also require naval capabilities for India to become a net security provider in the Indian Ocean.

- India has been pursuing regional as well as bilateral cooperation on maritime security in the Indian Ocean, engagements that now need greater intensity.

- It will also need naval assets that can work with other navies in protecting energy supply routes beyond the Indian Ocean, particularly in the South China Sea, from which new supplies of energy might flow in future.

Need of global energy regime:

India will have to identify the key functions that a regional or plurilateral energy institutions could perform, which would otherwise be hard to do unilaterally.

Functions:

- Assuring transparency in energy markets

- Cooperatively managing strategic reserves

- Jointly patrolling energy supply routes

- Arbitrating disputes, and pooling resources to lower insurance premiums on transporting resources.

There will be tough choices but either way India’s integration into global energy markets will be one of the key shifts in the global economy.

Connecting the dots:

- What does energy security mean? What are the threats and challenges faced by India’s energy security? Throw light on how to eliminate insecurity in India’s energy security?

MUST READ

The Aadhaar coup

Related Articles:

The Big Picture – Legislative Backing for Aadhaar: How will it help?

Getting smart with public transport

Related Articles:

India’s draft road transport and safety bill

Public transport: Overwhelming Needs but Limited Resources

A silent horticulture ‘revolution’– Technology-led gains in the productivity of horticultural crops have allowed farmers to diversify

Is the rupee close to its Goldilocks rate? Yes, suggests Raghuram Rajan- Is the Indian rupee overvalued? Or is it undervalued? RBI governor Raghuram Rajan’s recent remarks suggest that it may be neither

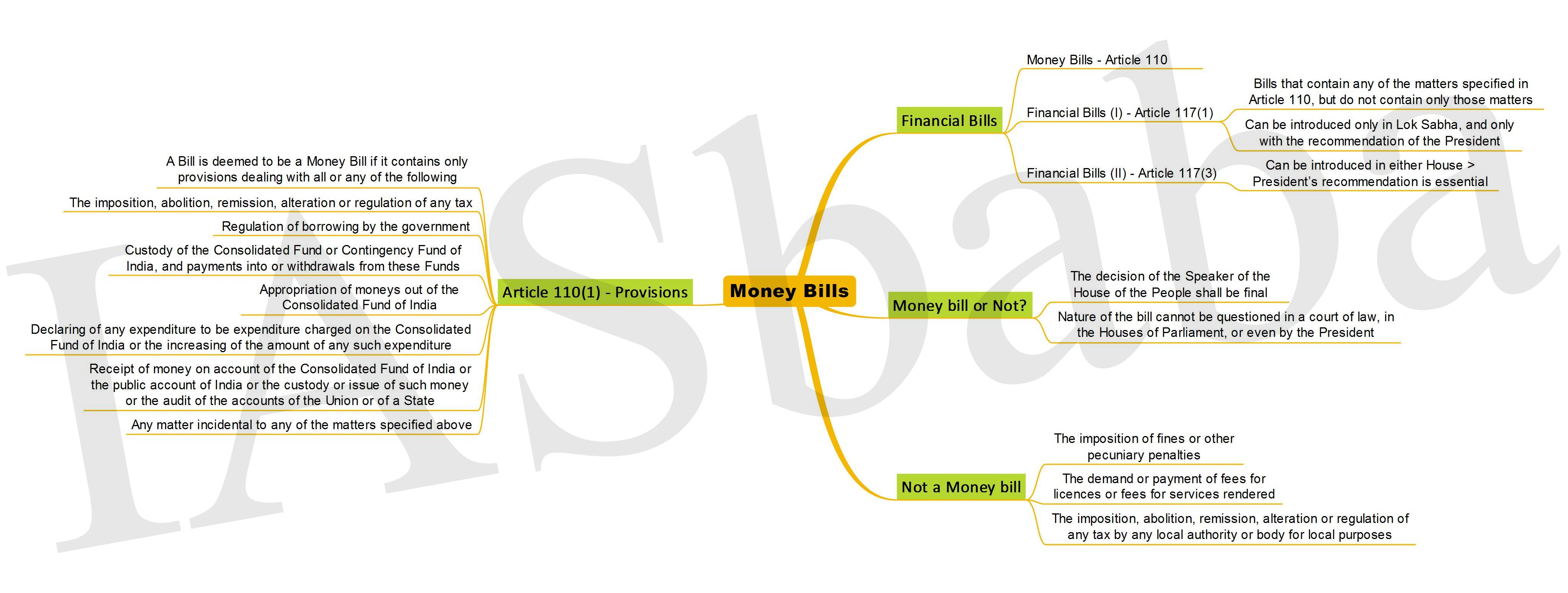

MIND MAPS

1. Money Bills