IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Aug 2016, National, UPSC

Archives

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 4th August, 2016

NATIONAL

TOPIC:

General Studies 2

- Structure, organization and functioning of the Executive and the Judiciary Ministries and Departments of the Government; pressure groups and formal/informal associations and their role in the Polity.

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

General Studies 3

- Infrastructure: Railways

Don’t merge rail and general Budgets

Why in news?

The merger of rail and general budget is making a flutter again with news of Railway Minister accepting the Bibek Diberoy committee recommendation of merging two budgets.

Knowing the rail budget history

- The railways were in poor shape in early 1900s.

- Rail facilities were inadequate

- The railway line building was very fragmented

- The state lines built by state

- The state line built by independent companies

- Company lines built by companies

- Railway lines of princely states

- Railways failed to meet the demand of passengers as well as trade. Goods used to rot on platforms. Waiting line and lists kept on increasing. Overcrowding was a common scene.

- The main reason was:-unavailability of funds for expansion, development, repair and maintenance.

Fund drought

- The railways were one of the important source of government fund. Yet, they had inadequate allocation of funds.

- Railway budget was the first casualty in times of bad harvest, lesser trade and revenue. There used to be reduction in staff and suspending the work in progress.

- When the situation improved, the railways were asked to make speedy development. However, limited time period was not able to make railways effective and efficient.

- Public demand for the appointment of a committee to enquire into the desirability of adopting direct state management of the Railways and liberating the utility from the finance department of the government was set before the Imperial Legislative Council vide repeated resolutions in 1914, 1915, 1917 and 1918.

The Acworth Committee

- A ten member (three Indians) committee was appointed with Sir Acworth as its chairman in 1920.

- The committee was given the task of going into the whole question of railway policy, finances and administration.

- The committee came to a conclusion that without radically reforming the railway financial administration, it was not possible to modernise, improvise and enlarge the Indian Railways.

- The committee was of the opinion that the essence of the railway reform was separation of railway budge from general budget.

- The issue of a separate rail budget was undertaken in 1924 on Acworth Panel’s recommendation in the Legislative Assembly. It stated that a different budget would enable the railways to spend money according to its needs and will not be impacted by the vagaries of general budget allocations.

- The rail budget was introduced in 1925-26

Support of General Budget continues

- Though the railways have been responsible for earning and spending their own money,

- Yet, time and again they have looked for budgetary support from general exchequer as the money earned by them has not been sufficient.

- The main reason has been the populist approach which has not allowed railways to increase fare and freight in tandem with rising cost of transportation.

- The passenger fares were subsidised from the goods transport. This in turn led to increase in road transport.

- This politicisation of railways was visible even after independence when India adopted parliamentary democracy.

- The rail budget became more of a vote bank building instrument rather than a commercial exercise.

- Such a practice and continued attitude has affected the finances in such a way that expansion, modernisation, development or replacement of worn-out tracks or rolling stock do not have adequate funds.

India’s stand in world

- Since Indian independence, the railways have achieved landmarks throughout the world

- China had 22,161 km in 1950. Today it has more than one lakh km rail lines.

- In India, there were 54,600 km railway lines in 1950. Only 11,000 have been added till now.

- China has achieved a 300kmph speed with the Beijing-Guangzhou bullet train service.

- India still has Rajdhanis and Shatabdis running at 130-140 kmph. Even the newly introduced Gatiman Express has attained the maximum speed of 160 kmph.

- The technology is not the contention, finances are.

- Indian engineers are equally capable of modernising the Indian railways. However, much of the rail budgets goes into subsidisation and other petty issues, whereas critical development sectors like R&D, expansion etc. face financial crunch. The support from general budget also remains tight.

- The external borrowings through Indian Railway Finance Corporation is also restricted

- Thus, separating rail budget from general budget did not actually bore fruits as anticipated as the political flaws took over the development aspect of rail sector.

Conclusion

Merging two is not the apt solution

- If the rail budget comes under general budget, its revenue and expenditure will get tied to general budget

- If there is a revenue shortfall in general budget, the finance ministry won’t cut out regular expenditure like staff salaries, fuels, stores and equipment.

- Instead, the axe will be on modernisation and expansion only.

- The finance minister will face the same constraint as Railway Minister while raising fares

- The merger will make Railways more like a government department and will lose its commercial identity

- There is contradictory opinion even by the experts: on one hand they want privatisation in railways and on other hand they suggest merging it into system, thereby subverting its commercial nature which requires separate financing.

The need is to maintain a status quo on separate budgets and concentrate more on strengthening, modernising and expanding the railways so as to meet its challenges of increased transportation and passenger travels.

Connecting the dots:

- Merging the railway budget and general budget will change the character of Indian railways. Critically analyse.

- With plethora of rail reforms taken up by the railway minister, it requires independent finances to plan and implement. Do you agree? Explain.

Refer:

Rail Budget 2016: A balance between growth, operation efficiency

The Big Picture – Railway Budget: What’s on offer?

ECONOMICS

TOPIC: General Studies 3

- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment.

- Inclusive growth and issues arising from it.

- Government Budgeting.

An analysis of potential benefits and implementation problems with GST regime

GST is an important indirect tax reform that has been on the cards for more than a decade.

What is GST?

- In simple terms, Goods and Services Tax is a unified indirect tax imposed on goods and services across the nation.

- In broader terms, GST is a comprehensive tax levy on manufacture, sale and consumption of goods and services at a national level.

- In principle, GST is same as the Value-Added Tax (VAT) – already adopted by all Indian States – but with a wider base. While the VAT was imposed only on goods, the GST will be a VAT imposed on both goods and services.

Current Tax Regime (without GST)

In the current tax regime, States tax sale of goods but not services. The Centre taxes manufacturing and services but not wholesale/retail trade.

The GST is expected to usher in a uniform tax regime across India through an expansion of the base of each into the other’s territory.

Under current tax regime, without the GST, there are –

- multiple points of taxation

- multiple jurisdictions

- imperfect system of offsetting credits on taxes paid on inputs, leading to higher costs

- cascading of taxes (tax on tax)

- inter-state commerce are hampered due to the dead weight burden on Central sales tax and entry taxes, which have no offset

All this will go once the GST is in place.

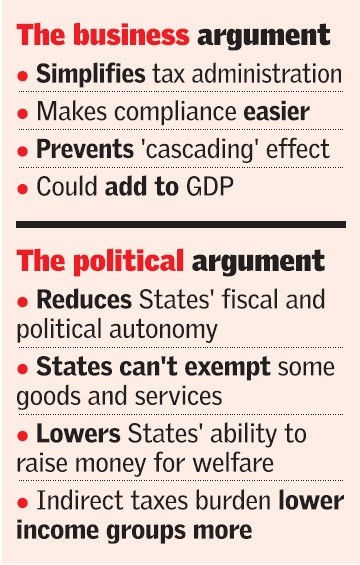

Why GST? What are its benefits?

GST will create a unified, un-fragmented national market and pushes competitiveness.

- GST, by subsuming an array of indirect taxes under one rubric, will simplify tax administration, improve compliance, and eliminate economic distortions in production, trade, and consumption.

- GST will widen the tax base and make it identical for both the Centre and States. (Unlike an excise duty whose base consists of manufacturers, the GST is paid only by the final consumer)

- By giving credit for taxes paid on inputs at every stage of the supply chain and taxing only the final consumer, it avoids the ‘cascading’ of taxes, thereby cuts production costs, and makes exports more competitive.

- GST will create a single market, enhances ease-of-doing business and make our producers more competitive against importers.

- GST will eliminate inter-state taxes and reduces black money, thus will free up some capital. All this will add to demand and also efficiency.

- According to the economists, thanks to these efficiencies, the GST will add 2 per cent to the national GDP. (at least GDP growth can go up by one percentage point on a sustained basis)

Co-operative Federalism:

The adoption of GST is an iconic example of

- ‘Cooperative Federalism’ and

- ‘Nationwide, multiparty consensus-building exercise’

Concerns (Potential implementation problems) with GST

- GST will not have a positive impact on : States’ Fiscal and Political Autonomy; States’ freedom

- On question of what is the right rate?

- Social dimension – GST, which is an indirect tax, is considered regressive

- Shift toward indirect taxation

- Issue of Tax Litigations

- States’ Fiscal and Political Autonomy

Only time will tell whether the GST will have a positive impact on the GDP. But there is one thing the GST will not have a positive impact on: the States’ fiscal, and therefore, political autonomy.

When we move to a GST regime, India will have not a single federal GST but a dual GST, levied and managed by different administrations.

- The Centre will administer the central GST (CGST) and the States will administer the SGST.

- Compliance will be monitored independently at the two levels.

- All goods and services will be divided into certain categories. The rate will be fixed by category and State cannot shift a commodity from a lower to a higher rate or put it in exempt category.

- The rates for both CGST and SGST will be fixed by the GST Council (whose Chairman will be Union FM and members will be State Finance Ministers/Revenue Ministers).

- Once rates are set by GST Council, individual states will lose their right to tax commodities at the rates they want.

There will be a steady erosion in the States’ freedom to decide on taxes and tax rates.

According to Constitution of India, States have complete autonomy over levy of sales taxes, which account for 80% of their revenue. An attempt was made to curtail this autonomy with the introduction of VAT but it did not succeed as VAT had 4 different rates that States could play with.

But with the GST, which mandates a uniform rate, even this limited authority will be gone. i.e., with GST virtually no taxing powers to the states.

If a State wants to undertake a special spending programme to respond to a State-specific situation, it cannot raise taxes on goods. So, innovative programmes and schemes such as Mid-day meal scheme by TN, NREGA scheme by Maharashtra which was initiated by States by raising their tax would not happen now as States does not have fiscal autonomy.

Uniform Tax regime could adversely impact States that are more committed to welfare expenditures and can’t initiate their own development philosophies (as they lose control over tax revenue)

Governance within the GST council

- GST council is a de-facto council of states along with the representatives from Union Finance Ministry.

- One State will get one vote irrespective of its size, which seems unfair.

- An economically larger states contributing bigger chunk to GST pie should have greater say. However, this is not the case.

- Special needs of the smaller states should also be heeded.

The GST regime should remain sympathetic to these issues of States’ fiscal and political autonomy. Still we are unsure how it may affect the third tier, i.e. local bodies.

- What is the right rate? How it is determined?

There are issues on question of what is the right uniform GST rate? What factors determine this uniform GST rate?

- 13th Finance Commission’s Task Force, 2010 on GST recommends a rate of 12% (i.e., 7% States GST and 5% Central GST = 12%)

- But now an empowered committee of finance ministers mooted a concept called “Revenue Neutral Rate” or RNR

“Revenue Neutral Rate” or RNR:

- A panel of State Governments representatives mooted a concept called RNR, where tax will remain same for Centre and States. (e., 12.77 CGST and 13.91 SGST = 27%)

- In other words, RNR, when applied will leave all states with the same revenues as before. No state loses out signing up GST.

- In trying to assuage the fears of States, the calculation of RNR has been loaded with every possible tax – entry taxes, octroi tax etc. This has caused RNR to escalate the GST rate to high 27%.

- However, this is a faulty approach as 27% GST imposes enormous tax burden on wage earning classes. We won’t be able to gauge the buoyancy of the GST.

In other words, if RNR is escalated à GST rate will also be escalated à this will burden the earning classes (hurting India’s income inequality) à kills the golden egg-laying goose (purpose of GST) à therefore, RNR is self-defeating.

Better approach is to keep GST rate low, but doing so will create revenue loss to States.

Therefore, the loss in revenue of the States should be compensated by the Centre at the same time maintain low GST rate.

- Indirect taxes are considered regressive and direct taxes are proportional

- GST is an indirect tax and could be regressive, because they affect the poor more than the rich.

- India’s ratio of indirect to direct tax collection is 65:35, which is exactly the opposite of the norms in most developed countries.

- India’s ratio of direct tax to GDP is one of the lowest in the world. Only 4% of Indians pay income tax. However, almost all Indians pay indirect taxes.

- Shift toward indirect taxation

Recently, indirect taxes are increasing whereas direct taxes are decreasing. To meet their fiscal needs, it is always tempting for governments to tweak indirect taxes higher, since the work of expanding the direct tax net is very much harder.

For example,

- Service Tax was 5% during 1990s, now it is 15%

- New indirect taxes such as Swatcch Bharat Cess, Education Cess are being added

- Excise duty on petrol and diesel have increased steadily

However, same progress or steady increase has not happened in direct taxes.

Therefore, the temptation of governments to increase indirect taxes can be curbed with a rate cap.

Unless a rate cap is adopted, GST rate could also easily drift higher hurting India’s income inequality.

- Tax Litigations:

Approx. Rs 1.5 lakh crore is struck in litigation related to Central excise and service taxes. Disputes and cases involving on Central taxes go through appeals and tribunal processes and can drag on years.

On the other hand the State-level VAT is administered in a way that empowers tax officials to dispose of cases quickly.

Therefore, GST should deploy same approach as the State-level model which is more efficient.

Conclusion:

The GST is obviously not a silver bullet for all ills of India’s economy. It is nevertheless a revolutionary and long-pending reform. It promises economic growth and jobs, better efficiency and ease of doing business and higher tax collection. However, its imperfections and potential pitfalls should be sorted out as the government rolls it out.

Connecting the dots:

- Discuss the potential benefits and implementation problems with adoption of GST.

- Why GST is seen as one of the biggest taxation reforms often called as big bang reform. How will it help in economic growth? Explain.

- Do you think that GST broadens the tax base, sharpen the competitive edge of Indian exports by several tax distortions and create a unified national market by removing inter-state barriers to trade?

- “The GST can be a big boon if it has right kind of rate and legislation.” Explain.

MUST READ

GST related articles in national dailies

The age of GST dawns

Good sense triumphs on the GST

Now, iron out the wrinkles

‘GST is one of the boldest reforms in post-Independence India’

GST: The road ahead for industry

Reforms and the disabled

Betrayal In The House

India’s damaging inflation debate

Tax terrorism: collecting taxes and then some more