IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs May 2017, IASbaba's Daily News Analysis, National, UPSC

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 26th May 2017

Archives

ECONOMICS

TOPIC: General Studies 3

- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment.

- Inclusive growth and issues arising from it.

How to deal with the mega challenge of job creation

Overview:

India may be the world’s fastest growing major economy, but the benefits of that growth do not seem to be percolating down to the masses. Job creation continues to be a major problem.

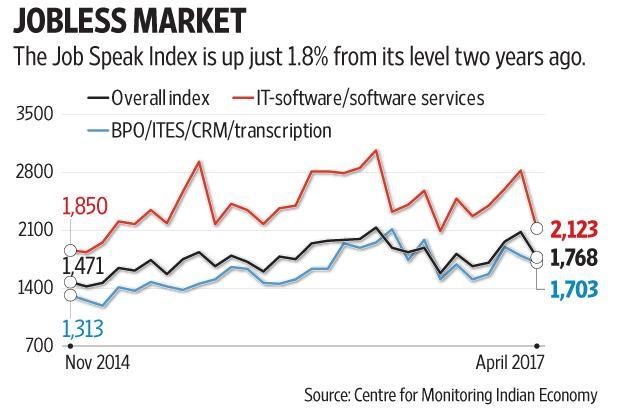

From the above Job Speak Index graph, we can observe that

- The overall index for April 2017 was lower than where it was in July 2015.

- New job creation is lower than that of 2015 or 2016.

- Among sectors, the worst hit was the information technology (IT)-software industry, which saw a 24% year-on-year drop in hiring.

- Other key industries like construction and business process outsourcing/IT enabled services too saw a 10% and 12% decline in hiring, respectively.

NSSO’s contrasting view on Unemployment:

The latest National Sample Survey (NSS) data for 2011-12, however, show unemployment was only 2.2% of the labour force, which is very low. On this metric, unemployment in India is much less of a problem than in other countries.

The low unemployment rates are misleading because many of those shown as employed are actually engaged in low-paid jobs that they take up only because there is no alternative. Economists call this “disguised unemployment” or “underemployment”.

A recent survey of youth unemployment shows that educated youth face greater problems. The unemployment rate for 18-29-year-olds as a group is 10.2%, but for illiterates it is only 2.2%, rising to 18.4% for graduates. As more and more educated youth enter the workforce in future, the policy makers should make sure that unless the quality of jobs available for them improves dramatically, dissatisfaction will mount.

What needs to be done to tackle this problem?

At the macro level, three structural changes are needed to tackle the problem.

First, the workforce employed in agriculture must decline.

- In 2011-12, agriculture accounted for 18% of gross domestic product (GDP) and it absorbed about 50% of the workforce.

- That means, Productivity per person in agriculture was therefore 18/50 = 36% of the national average.

- If the economy as a whole grows at 7.5% per year over the next 10 years, and agricultural growth accelerates to 4%, the share of agriculture in GDP will fall to around 11% by 2027-28.

- To maintain agricultural productivity at say 36% of the national average, the share of employment should decline to 31%. This is almost certainly too sharp a decline, but even if the employment share declines to 35%, it implies a major shift out of agriculture.

- This places a huge burden of on non-agricultural employment, which will have to expand sufficiently to absorb the shift out of agriculture plus the normal increase in the total workforce.

The second structural change needed is to reduce the expectation from manufacturing as a provider of non-agricultural jobs.

- Faster growth in manufacturing has long been central to our economic strategy and must remain so. However, policy makers have to recognize that technological change is likely to make manufacturing less employment generating than in the past.

- The problem of automation leading to fewer jobs is not limited to IT-software alone. A sector like manufacturing is also opting for automation to remain cost- effective. With not much capacity addition happening, job creation is expected to remain subdued.

- Even if Artificial Intelligence and 3D printing are distant developments in India, there can be no doubt that any successful manufacturing strategy will involve application of capital-intensive techniques, especially if the country proposes to integrate more fully with the world and with global supply chains.

- At present, manufacturing accounts for about a quarter of total non-agricultural employment. Another quarter comes from non-manufacturing industry (mining, electricity and construction) with services accounting for the remaining half.

- Most of the growth needed in non-agricultural employment will have to come from construction and the services sector, including health services, tourism-related services, retail trade, transport and logistics and repair services. A careful review of policies is needed to see how impediments to expansion in these sectors can be removed.

The third structural change needed is a shift from informal sector employment to formal sector employment.

- The NSS data for 2011-12 showed about 243 million people employed in the non-agricultural sector, and as many as 85% of these were in the “informal sector”, including both self-employment and wage employment.

- However, much of the demand for “high quality” employment opportunities today is a demand for jobs in the formal/organized sector.

- A shift away from the unorganized/informal sector to the organized/formal sector is desperately needed if the government wants to meet the expectations of the young.

Solution:

To achieve all the above stated structural changes, multiple interventions are needed at different levels.

- Focus on Rapid Growth

- Rapid growth has to be central to any employment strategy for the simple reason that a faster growing economy will generate more jobs.

- Avoid generating low quality, low productive employment

- Any notion of generating the employment needed without high growth would be seriously misleading. Government can end up probably generating low quality, low productivity employment even if they fail on the growth front, but that is not what young people want. This means all the policies that are likely to accelerate growth are also critical for generating employment.

- Manufacture and export simpler consumer goods

- The biggest opportunity for generating more employment in manufacturing lies in exporting simpler consumer goods to the world market, an area which China has long dominated, but which it is now likely to exit, as its wages rise.

- Modernization of small industries

- However, in order to obtain above goal, it depends on how well India has ability to compete with others such as Bangladesh, Vietnam.

- Paradoxically, becoming competitive would involve faster modernization of these (simple consumer goods) industries, which will involve a shift away from labour intensity, but if it allows an increase in the scale of operations, total employment could increase.

- Focus on Small and Medium scale enterprises

- Small and medium enterprises generate much more employment than large capital-intensive enterprises but we have not done enough to encourage this segment. India’s industrial structure suffers from what is called “the missing middle”.

- There are a few large enterprises, as is the case every where, and at the other end there are a large number of firms at the very small or micro level. There are too few middle-sized firms, employing between 100 and say 1,000 workers, and it is these firms that can upgrade technology, increase productivity, and demonstrate competitiveness in world markets.

- Solve the problem of missing middle

- The policies needed to develop this middle group include lowering of corporate tax rates and abolition of incentives that favour more capital-intensive units.

- Better public infrastructure, especially access to quality power supply at reasonable rates, improved logistics, greater ease of doing business, better access to finance, ample availability of skilled labour, and more flexible labour laws – can help these middle enterprises to grow.

- Development of skills through a combination of apprenticeships and training institutes run by the private sector, with an eye to the demand for skills in the market, is also critical.

- Foster trade with other countries

- India has the advantage of being located in Asia, which is the fastest-growing region in the world and which has not turned inward. India should work to reach an early conclusion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) + 6.

- Encourage entrepreneurship and Start-ups

- Start-ups are a new phenomenon and India has made a good beginning in this area. Technically skilled and business-oriented youth should be encouraged to explore the entrepreneurship option, and create jobs, rather than looking for secure wage employment.

- The ecosystem required for start-ups to flourish includes scientific and technical universities acting as innovation hubs, tax policies which encourage angel investing and other forms of start-up financing, a legal system which supports high standards of corporate governance, and supportive tax policies which encourage start-up financing.

- Promote shift from unorganized/informal to the organized/formal sector

- Finally, the government should deploy all policy instruments to promote the shift from the unorganized/informal to the organized/formal sector, both manufacturing and services.

- In the past, there has been a tendency to view the unorganized sector as a potential source of employment, and this has at times been used to justify a more lax attitude, especially in the matter of applying regulations (as discussed in our previous article – Link: The role of India’s Informal Economy: Informal is the new normal). Ideally, all discrimination against the organized/formal sector should be phased out to create a level playing field.

- Favourable reforms in safety regulations and tax norms, labour laws, ease-of-doing business and more incentive for units will help informal units move progressively into the organized/formal sector.

Conclusion:

To sum up, all the above said measures if implemented effectively will lead to both generation of employment and improvement in quality of employment, which is a major concern today. Unless more jobs are created, India’s demographic dividend will turn into a nightmare.

Connecting the dots:

- Will the long-awaited revival in private sector investment aid massive job creation? Critically analyze.

- Unless more jobs are created, India’s demographic dividend will turn into a nightmare. In your opinion, what immediate policy measures are required to tackle the problem of generation of employment and improvement in quality of employment? Discuss.

- Job creation is taking place in the informal sector, there is a need to get them into the formal fold. Do you agree with this view? Give arguments in favour of your answer.

NATIONAL

TOPIC: General Studies 2

- Structure, organization and functioning of the Executive and the Judiciary Ministries and Departments of the Government; pressure groups and formal/informal associations and their role in the Polity.

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

- Important aspects of governance, transparency and accountability, e?governance? applications, models, successes, limitations, and potential; citizens charters, transparency & accountability and institutional and other measures.

Bail Reforms

Introduction

Indian criminal justice system needs urgent reforms. One of the crucial aspect of the reform is under trials being languishing jails for years together. Bail system has unequally favored the rich and the haves. The Law Commission’s report serves a reminder of the same.

Under-trials in Indian Jails:

The ‘Prison Statistics India 2015’ report was released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) on Monday. Here are five things the data tells us about the state of Indian prisons.

- The problem of overcrowding – The report calls overcrowding as “one of the biggest problems faced by prison inmates.” It results in poor hygiene and lack of sleep among other problems. “Keeping in view the human rights of the prisoners, it is essential that they are given reasonable space and facilities in jails,” the report says.

- The occupancy rate at the all India level at the end of 2015 was 114.4 per cent – At 276.7 per cent, Dadra & Nagar Haveli is reported to have most overcrowded prisons, followed by Chhattisgarh (233.9 per cent), Delhi (226.9 per cent), Meghalaya (177.9 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (168.8 per cent).

- Two-thirds of the prisoners are undertrials – Sixty-seven per cent of the people in Indian jails are undertrials — people not convicted of any crime and currently on trial in a court of law.

- On an average, four died every day in 2015 – In 2015, a total of 1,584 prisoners died in jails. 1,469 of these were natural deaths and the remaining 115 were attributed to unnatural causes.

Two-thirds of all the unnatural deaths (77) were reported to be suicides while 11 were murdered by fellow inmates — nine of which were in jails in Delhi.

- Foreign Convicts – Over two thousand foreign convicts (2,353) were lodged in various jails in India at the end of 2015. The highest number of foreign convicts — 1,266 — were in jails of West Bengal, followed by Andaman & Nicobar Island (360), Uttar Pradesh (146), Maharashtra (85) and Delhi (81).

- Prisoner Profile – Seventy per cent of the convicts are illiterate or have studied only below class tenth.

- Capital Punishment – Over hundred people were awarded death penalty (101) in 2015. Forty-nine were commuted to life sentence.

Issue:

- That bail is the norm and jail the exception is a principle that is limited in its application to the affluent, the powerful and the influential.

- The Law Commission, in its 268th Report, highlights this problem once again by remarking that it has become the norm for the rich and powerful to get bail with ease, while others languish in prison.

- While making recommendations to make it easier for all those awaiting trial to obtain bail, the Commission, headed by former Supreme Court judge B.S. Chauhan, grimly observes that “the existing system of bail in India is inadequate and inefficient to accomplish its purpose.”

- One of the first duties of those administering criminal justice must be that bail practices are “fair and evidence-based”.

- “Decisions about custody or release should not be influenced to the detriment of the person accused of an offence by factors such as gender, race, ethnicity, financial conditions or social status,” the report says.

- The main reason that 67% of the current prison population is made up of undertrials is the great inconsistency in the grant of bail.

- Even when given bail, most are unable to meet the onerous financial conditions to avail it.

- The Supreme Court had noticed this in the past, and bemoaned the fact that poverty appears to be the main reason for the incarceration of many prisoners, as they are unable to afford bail bonds or provide sureties.

- The Commission’s report recommending a set of significant changes to the law on bail deserves urgent attention.

Law Commission’s reform suggestions:

- The Commission seeks to improve on a provision introduced in 2005 to grant relief to thousands of prisoners languishing without trial and to decongest India’s overcrowded prisons.

- Section 436A of the Code of Criminal Procedure stipulates that a prisoner shall be released on bail on personal bond if he or she has undergone detention of half the maximum period of imprisonment specified for that offence.

- The Law Commission recommends that those detained for an offence that would attract up to seven years’ imprisonment be released on completing one-third of that period, and those charged with offences attracting a longer jail term, after they complete half of that period.

- For those who had spent the whole period as undertrials, the period undergone may be considered for remission.

- In general terms, the Commission cautions the police against needless arrests and magistrates against mechanical remand orders.

- It gives an illustrative list of conditions that could be imposed in lieu of sureties or financial bonds.

- It advocates the need to impose the “least restrictive conditions”. However, as the report warns, bail law reform is not the panacea for all problems of the criminal justice system.

Conclusion:

Be it overcrowded prisons or unjust incarceration of the poor, the solution lies in expediting the trial process. For, in our justice system, delay remains the primary source of injustice. The Law Commission’s report needs to be implemented in letter and spirit and large scale criminal justice reforms need to be initiated.

Connecting the dots:

- Critically analyse the need for criminal justice reforms in the Indian scenario in light of report of Law Commission and National Crime Record Bureau.

MUST READ

Should agricultural income be taxed?

Wooing the Indian vote

Beyond triple talaq

Love to hate the RTI

The cycles of distress in Indian agriculture

India’s dismal record in healthcare

Reboot on RCEP

Why a rail development authority?

The maker of modern India