Governance, Indian Polity & Constitution

Baba’s Explainer – OBC Reservations

Syllabus

- GS-2: Governance & Policy Measures

- GS-2: Equality & Equity

Why In News: Supreme Court has stayed 27 percent reservation for OBCs in local body polls in Madhya Pradesh.

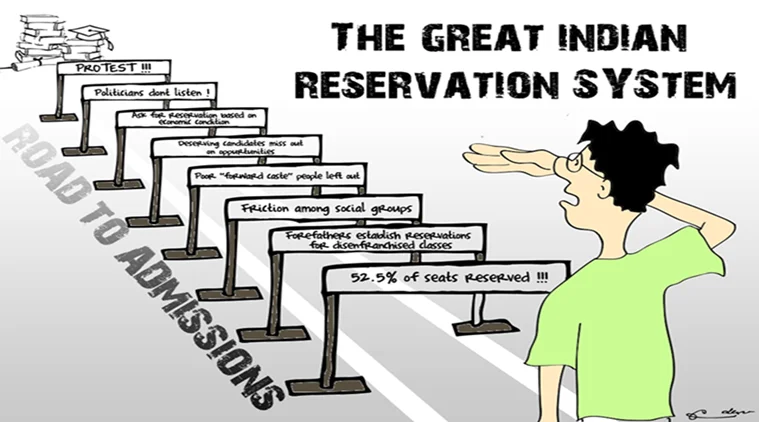

- In simple terms, reservation in India is all about reserving access to seats in the government jobs, educational institutions, and even legislatures to certain sections of the population.

- Also known as affirmative action, the reservation can also be seen as positive discrimination.

- The two main aims to provide reservation as per the Constitution of India are:

- Advancement of the sections of society that is considered as backward

- Scheduled Castes (SC) and the Scheduled Tribes (ST) (Article 15 (4)

- Any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens (OBC) Article 15 (5)

- Economically weaker sections (EWS) –and Article 15 (6)

- Adequate representation of any backward class of citizens (Article 16 (4)) OR economically weaker sections (EWS) in the services under the State (Article 16 (6))

- The use of the term OBC goes back to the Madras Presidency in the 1870s. The British administration combined shudras and ‘Untouchable’ castes under the label “backward classes” to identify lower caste groups for affirmative action.

- Untouchables were reclassified as SCs in the 1935 Government of India Act. After Independence, the Indian government continued to use this classification.

- Untouchability was abolished in 1950 and the state mandated political representation for SCs and STs at both central and state levels. The Constitution had also resolved to make provisions for OBCs.

- During the debate on Draft Article 10(3) which is the present Article 16(4) of the Indian Constitution, the term “backward class” was included.

- Article 16(4) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State.

- Immediately after India becoming a republic, the Indian Supreme Court in its two judgements in State of Madras Champakam Dorairarajan and Venkatraman v. State of Madras invalidated reservation for backward classes in educational institutions and in public services respectively, in the then State of Madras.

- In response to this, the provisional parliament amended the Constitution (First Amendment) to nullify the Supreme Court’s judgement and pave the way for reservation for backward classes.

- Speaking during the debates on the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill of 195, Dr B. R Ambedkar termed the judgements of the Supreme Court as “utterly unsatisfactory “ and “not in consonance with the articles of the Constitution”.

- In fact, first Backward Classes Commission under the chairmanship of social reformer Kaka Kalelkar was appointed as early as 1953 to determine the criteria for assessing backwardness.

- The commission submitted its report in March 1955 and considered caste a relevant criterion to determine backwardness

- It listed 2,399 backward castes or communities, with 837 of them classified as ‘most backwards’.

- The report was never implemented.

- Eventually, it took another Commission (Second Backward Classes Commission under Mandal) and almost forty years to implement reservation for OBCs.

- In exercise of the powers conferred by Article 340 of the Constitution, the President appointed a backward class commission in December 1978 under the chairmanship of former chief minister of Bihar B. P. Mandal.

- Article 340: The President may by order appoint a Commission to investigate the conditions of socially and educationally backward classes within India and to make recommendations as to the steps to be taken by the State.

- Mandal commission was formed to determine the criteria for defining India’s “socially and educationally backward classes” and to recommend steps to be taken for the advancement of those classes.

- Mandal submitted his report two years later, on December 31, 1980. By then, the Morarji Desai government had fallen and Indira Gandhi came to power. It remained in deep freeze during her term and that of Rajiv Gandhi.

Some of the recommendations of Mandal Commission are:

- Mandal Commission report estimated that OBCs constituted nearly 52 per cent of India’s population, excluding Scheduled Castes/Tribes (SC/STs.)

- OBCs among Hindus were identified based on socio-educational field surveys, lists of OBCs notified by various State governments, the 1961 Census report, and extensive touring of the country.

- Among non-Hindus, the caste system was not found to be an inherent part of the religion. However, for equality, OBCs were identified as untouchables converted from Hinduism and occupational communities known by their traditional hereditary jobs, such as the Gujjars, Dhobis, and Telis.

- Hence, for the inclusion of OBCs, the report recommended a 27 per cent reservation for these communities in government services and central/State educational institutions. That reservation was also made applicable to promotion quotas at all levels.

- However, children of government officials at higher posts, civil servants, high-ranking armed forces officers, professionals in trade, and so-called ‘creamy layer’ individuals are to be excluded from OBC reservations.

- According to a 2017 order issued by the Centre, creamy layer individuals are those who have an annual income of Rs 8 lakhs or more, disqualifying them from benefits under the OBC quota.

- The ‘creamy layer’ threshold has been gradually increased from Rs 1 lakh/year in 1993 to Rs 2.5 lakhs, Rs 4.5 lakhs, Rs 6 lakhs and now Rs 8 lakhs.

- The reserved quota, if unfilled, should be carried forward for a period of 3 years and dereserved after that.

- The government to make the necessary legal provisions to implement these recommendations.

- Age relaxation for OBCs to be the same as that for SCs and STs.

On August 7, 1990, then PM V P Singh announced in Parliament that his government had accepted the Mandal Commission report.

- V P Singh led-Central government wanted to implement the Mandal Commission report in 1990, but it was challenged in the Supreme Court.

- The verdict in the Indira Sawhney case, which came up before a nine-judge bench, was delivered in 1992.

- The Mandal moment saw ferocious backlash by sections of upper castes, particularly in northern & western regions of India

- This opposition was articulated on two axes

- That reservations compromised merit

- If at all reservations should open up beyond what was offered to SC & STs, it should be on economic lines (and not on caste basis)

What has been the Supreme Court’s verdict on OBC reservation?

The Supreme Court dealt with Constitutional Validity of OBC reservation in ‘Indira Sawhney’ Case or Mandal Case. The Supreme Court’s nine-judge panel gave the following verdict with a 6:3 majority on November 16, 1992:

- The SC upheld the 27% reservation for OBCs .

- Backward classes under Article 16(4) cannot be identified on the basis of economic criteria but the caste system also needs to be considered.

- Article 16(4) is not an exception to clause 1 but an instance of classification as envisaged by clause 1.

- Backward classes in article 16(4) were different from the socially and educationally backward mentioned in Article 15(4).

- SC also said that the ‘creamy layer’ among the OBCs should not be the beneficiaries of the reservations.

- It also held that there will be no reservation in promotions.

- Supreme Court in the same case also upheld the principle that the combined reservation beneficiaries should not exceed 50% of India’s population.

- Apex court also suggested permanent Statutory body to examine complains of over – inclusion / under – inclusion. So the Govt. set-up a statutory body called National Commission for Backward Classes as a permanent body.

- Any new disputes regarding criteria were to be raised in the Supreme Court only.

- Backlash by left out sections: The resentment of those communities which did not have a share in the reservation pie increased. Mandal Politics launched an era of open hostility between upper castes & backward communities, particularly in the Hindi heartland

- Appeasement Politics: Political parties, in order to appease their constituents, continued to expand reservation. This has undermined the entire purpose of reservation, envisaged as a tool to address historic injustice.

- Lack of Effective Implementation: As per the Report submitted by the Department of Personnel and Training to NCBC in 2020, OBC representation in Central government jobs (data of 42 ministries/departments) was found out to be:

- 16.51 % in Group-A central government services.

- 13.38 % in Group-B central government services.

- 21.25 % in Group-C (excluding safai karamcharis).

- 17.72 % in Group-C (safai karamcharis).

- Demand for Subcategorization of OBCs: Within OBCs, some communities benefited more than others, which led to a political divide and demands for sub-categorisation, a process currently underway.

- According to the Rohini Commission, out of almost 6,000 castes and communities in the OBCs, only 40 such communities had gotten 50% of reservation benefits for admission in central educational institutions and recruitment to the civil services.

What is Rohini Commission?

- The Rohini Commission, set up in October 2017 to examine the issue of Sub-categorization within Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in the Central List.

Commission’s Terms of Reference (ToR):

- Examining Inequality: To examine the extent of inequitable distribution of benefits of reservation among the castes or communities included in the broad category of OBCs with reference to such classes included in the Central List.

- Determining Parameters: To work out the mechanism, criteria, norms and parameters in a scientific approach for sub-categorisation within such OBCs.

- Classification: To take up the exercise of identifying the respective castes or communities or sub-castes or synonyms in the Central List of OBCs and classifying them into their respective sub-categories.

- Eliminating Errors: To study the various entries in the Central List of OBCs and recommend correction of any repetitions, ambiguities, inconsistencies and errors of spelling or transcription.

Challenges Before the Commision:

- Data Deficiency: Absence of data for the population of various communities to compare with their representation in jobs and admissions.

- Delaying of Survey: It was decided in Census 2021, data of OBCs will also be collected, but no consensus has been reached regarding enumeration of OBCs in the Census.

Findings of the Commission Until Now:

- In 2018, the Commission analysed the data of 1.3 lakh central jobs given under OBC quota over the preceding five years.

- It also analysed OBC admissions to central higher education institutions, including universities, IITs, NITs, IIMs and AIIMS, over the preceding three years. The findings were:

- 97% of all jobs and educational seats have gone to just 25% of all sub-castes classified as OBCs.

- 24.95% of these jobs and seats have gone to just 10 OBC communities.

- 983 OBC communities (37% of the total) have zero representation in jobs and educational institutions.

- 994 OBC sub-castes have a total representation of only 2.68% in recruitment and admissions.

- It is widely understood that the report could have huge political consequences and face a judicial review so it’s still not released and the commission has been given subsequent extensions

- Even though there is one list (decided by Parliament) that is maintained for SC & ST for reservation benefits, in case of OBCs, States were empowered to maintain their own list of OBCs so provide necessary benefits to them. Thus, we have

- Union OBC list for reservation in Central government jobs & Central Educational institutions

- OBC lists at State level (varies with each state) for reservation in State government jobs & State Educational institutions.

- The Constitution (102nd Amendment) Act, 2018 had granted constitutional status to the National Commission for Backward Castes (NCBC). It further inserted:

- Article 338B, which deals with the structure, duties and powers of the NCBC

- Article 342A, which deals with the powers of the President to notify a particular caste as an SEBC and the power of Parliament to change the list.

- However, Supreme Court (in Marata Reservation case) on 5 May 2021 had ruled that only the Centre had the power to draw up the OBC list, as per the above interpretation of Constitution (102nd Amendment) Act (Article 342A only mentions President & Parliament with no reference to states)

- This verdict was opposed by the States for they would lose their power of notifying OBCs.

- It was estimated that nearly 671 OBC communities would have lost access to reservation in educational institutions and in appointments if the state list was abolished.

- Moreover, nearly one-fifth of the total OBC communities would have been adversely impacted by this.

- To reverse the verdict and to restore the powers of the state governments to maintain state list of OBCs, Parliament passed 127th Constitution Amendment Bill, 2021

- Amendment in Articles 366(26C) and 338B (9), after which states will be able to directly notify OBC and SEBCs without having to refer to the NCBC, and the “state list” will be taken out of the domain of the President and will be notified by the Assembly.

- Each State has listed communities which are recognised as OBCs and accorded them reservations accordingly.

- There is no reservation for OBCs in Lakshadweep, Tripura, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh due to the absence of any citizens belonging to OBC communities.

- To ensure political representation, of the 543 seats in Lok Sabha, 84 seats are reserved for SCs, 47 seats for STs and 2 for Anglo-Indian members (nominated by the President).

- SC/ST communities have reservations in their respective State Assemblies, councils and local bodies too.

- However, for OBC communities, there are no separate political reservations in State legislatures or local bodies.

- In a bid to alter this, the Maharashtra government passed an Ordinance to introduce a 27-per-cent reservation for OBCs in Zilla Parishads and Panchayat Samitis. However, in December 2021, the SC struck down the Ordinance citing the 50-per-cent threshold rule for reservation.

- In Indira Sawhney vs Union of India (1992), the Supreme Court had upheld the 50-per-cent ceiling on reservations, thereby limiting states’ powers.

- Despite the apex court upholding the 50-per-cent ceiling, many communities have sought separate reservations at the State and Central levels across India.

- The most notable protests have included those of the Gujjars (Rajasthan) seeking their reclassification from OBC to STs and five-per-cent reservation. Similarly, Patidars (Gujarat) and Jats (UP, Rajasthan, Delhi) have been seeking inclusion as OBCs.

- Since the inclusion of the 10-per-cent EWS quota, most States have breached the 50-per-cent cap on reservations.

- Topping the list is Tamil Nadu (69 per cent), followed by Chhattisgarh (69 per cent), Maharashtra (62 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (60 per cent), Bihar (60 per cent), Delhi (60 per cent), Jharkhand (60 per cent), Karnataka (60 per cent), Kerala (60 per cent), Madhya Pradesh (60 per cent), Telangana (60 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (60 per cent.)

- Recently, the call for reconsidering the 50-per-cent cap has been growing since several States have been demanding a caste census to determine the actual population of SCs, STs, OBCs, and minorities.

- However, the Centre has maintained that the caste census data of 2011 is unusable as it was “fraught with mistakes and inaccuracies”. It has also refused to conduct a nationwide caste census in 2022.

Mains Practice Question – Do you think, there is a need to review the reservation structure? Critically Comment.

Note: Write answers to this question in the comment section.