Governance, Indian Polity & Constitution

Context:

- The Election Commission of India (ECI) could not demonstrate a prototype of its new Remote Electronic Voting Machine (RVM), which would allow domestic migrants to vote in national and regional elections.

- EVMs started being used on a larger scale in 1992 and since 2000, have been used in all Lok Sabha and State Assembly elections.

About Remote Voting Machines:

- The Multi-Constituency RVM for migrant voting will have the same security system and voting experience as the EVM.

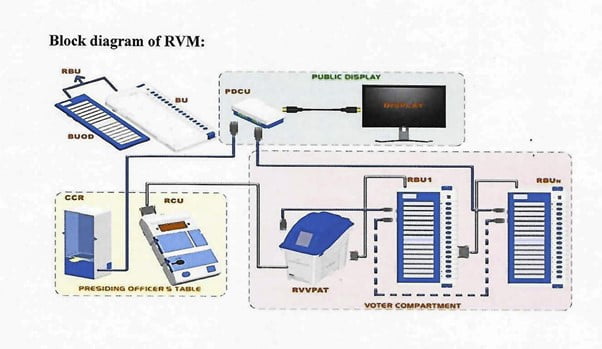

- RVM can handle multiple constituencies (up to 72) from a single remote polling booth.

- For this, instead of a fixed ballot paper sheet, the machine has been modified to have an electronic dynamic ballot display which will present different candidate lists corresponding to the constituency number of the voter read by a constituency card reader.

- The ECI has added a digital public display unit or a monitor to act as an interface between the constituency card reader and the BU display.

- the electronic ballot will be prepared by the Returning Officers (ROs) of home constituencies of voters, and forwarded to the remote RO for uploading in the SLU.

Concerns of RVM:

- Lack of clarity on how these new devices communicate with each other, Whether it is a device with programmable memory

- Question on integrity – would it be possible to mess with the digital display to show a modified list to the voter, since the unit is connected to an external device for symbol loading

- Logistical and administrative challenges – including voter registration in remote locations, how names will be removed from the electoral rolls of the home constituency, how remote voting applications will be made transparent etc.

- Further, the challenges regarding the current EVMs will persist when it comes to the RVMs.

How do existing EVMs work?

- The latest EVM is an M3 model which was manufactured from 2013 onwards.

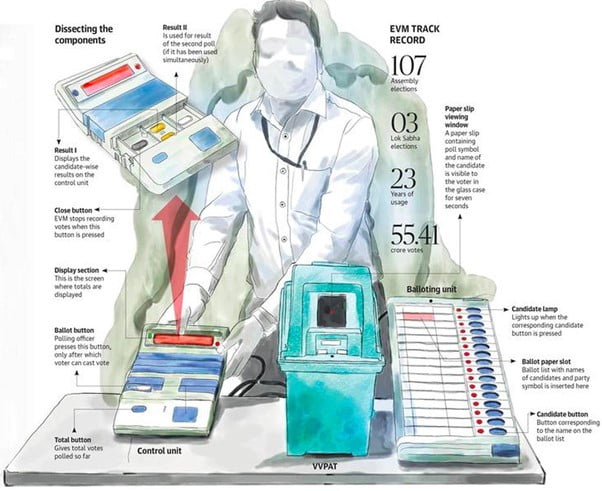

- It has a Balloting Unit (BU) which is connected to the VVPAT printer, both of which are inside the voting compartment.

- The VVPAT is connected to the Control Unit (CU), which sits with the Presiding Officer (PO) and totals the number of votes cast, on its display board.

- Only once the PO presses the ballot button on the CU, does the BU get enabled for the voter to cast her vote by pressing the key corresponding to the candidate on the ballot paper sheet pasted on the BU.

- The VVPAT, which is essentially a printing machine, prints a slip with the poll symbol and candidate name, once the voter presses the key on the BU.

- This slip is visible to the voter on the VVPAT’s glass screen for seven seconds after which it gets dropped off in a box inside the VVPAT.

- Once a vote is cast, the BU becomes inactive till the PO schedules the next vote by enabling it again from the CU

Voter Verified Paper Trail Audit (VVPAT)

- Developed by ECI along with two Public Sector Undertakings (PSU), in 2010

- It is a mechanism that could help verify that the EVM had recorded the vote correctly as intended by the voter

- The use of VVPATs has become universal in elections since mid-2017.

- To create a VVPAT sheet on the laptop, an application is either downloaded from the ECI server or copied from a local device.

- It is then uploaded to another device or the Symbol Loading Unit (SLU) through a nine-pin cable, which in turn is connected to the VVPAT for upload. This process raises questions.

Significance of Indian EVMs

- They are standalone, are not connected to the internet, and have a one-time programmable chip, making tampering through the hardware port or through a Wi-Fi connection impossible.

- As per ECI, EVMs are “robust, secure, and tamper-proof”, owing to the technical and institutional safeguards in place.

- Such as the sealing of machines with signatures of polling agents, first-level checks, randomisation of machines, and a series of mock polls before the actual voting, cannot be circumvented.

Concerns about EVMs:

- A 2021 report titled, ‘Is the Indian EVM and VVPAT System Fit for Democratic Elections?’ highlighted the widely recognised ‘democracy principles’ to be adhered to while conducting public elections.

- Lack of transparency – Details of the EVM design, prototype, software, and hardware verification are not publicly available for technical and independent review, rendering it available only for a black-box analysis, where information about its inner workings is not accessible.

- EVM tampering – claim that EVM tampering through a WIFI connection is not possible has been disrepute by multiple computer scientists as it does not take into account ‘side-channel’, insider fraud, and trojan attacks.

- Besides, the OTP chip which cannot be rewritten, also has a flip side

- Outsourcing – The ECI sends the EVM software to two foreign chipmakers (in the U.S. and Japan) to burn into the CPU and the manufactured chips are then sent to India for assembly into machines by the two PSUs (BEL and ECIL).

- This means that the manufacturers cannot read back the contents of the software to ensure its integrity is intact.

- Functionality tests done by manufacturers can only reveal if the machine is working properly.

- Hacking – A fixed number of votes are casted at the beginning of the polls in each polling station. Thus, a hack can easily bypass the first few votes, thereby preventing detection of foul play as every key press in the EVM is date and time stamped”.

Concerns with VVPAT:

- EVM Tampering – Even if the voting machine is tampered, the same should be detectable in an audit.

- Machine dependence – For the voting process to be verifiable and correct, it should be machine-independent, or software and hardware independent, meaning, the establishment of its veracity should not depend solely on the assumption that the EVM is correct.

- Voter verification – The current VVPAT system is not voter verified in its full sense, meaning, while the voter sees their vote slip behind the VVPAT’s glass for seven seconds, it does not mean they have verified it.

- Vote cancellation – That would happen if the voter got the printout in their hand, was able to approve it before the vote is finally cast, and was able to cancel if there is an error.

- Former IAS officer Kannan Gopinathan, notes “voter should have full agency to cancel a vote if not satisfied; and that the process to cancel must be simple and should not require the voter to interact with anybody

- Voter penalisation is discouraging – Under the current system, if the voter disputes what they have seen behind the screen, they are allowed a test vote in the presence of an election officer, and if the outcome of the test vote is correct, the voter can be penalised or even prosecuted

- Questionable Assurance – by ECI that the EVM-VVPAT system is not connected to any external device has been questioned by former civil servants.

- Since, for the VVPAT to be able to generate voting slips, the symbols, names and the sequence of the candidates need to be uploaded on it which is done by connecting it to a laptop.

- Opacity regarding communication protocol – If the VVPAT is cleared and loaded with new information for every election, does this mean it has a programmable memory? These questions remain unaddressed.

Way forward

- Ronald Rivest, an MIT professor and the inventor of encryption, defined that “a voting system is software (hardware) independent if an undetected change in software (hardware) cannot lead to an undetectable change in the election outcome”

- Elections should uphold the democratic principles – The election process should not only be free and fair but “also be seen to be free and fair”, meaning instead of being told to trust the process the general public should be provided with provable guarantees to facilitate this trust.

Source: The Hindu