IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs June 2016, National, UPSC

Archives

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 25th June, 2016

NATIONAL

TOPIC: General studies 2: Governance

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation

- Important aspects of governance, transparency and accountability, e-governance- applications, models, successes, limitations, and potential citizens charters, transparency & accountability and institutional and other measures.

Post-legislative scrutiny – for better governance and better country

The below article argues for developing a policy tool which can regulate and review the laws that are already enacted and implemented.

In other words, there is an urgent need for Post-legislative scrutiny to improve the quality of laws.

Why there is a need for ‘Post-legislative scrutiny’?

- India, a country which has one of the highest numbers of laws on its statute books, however, its implementation record is distressingly poor.

- One of the reasons for the poor performance, aside from design issues, capacity constraints and corruption, is the near-complete absence of post legislative scrutiny or review of the laws.

- Post-legislative reviews can assess whether the objectives and the anticipated effects of legislation have actually taken place on the ground.

- Various governments have taken small steps in the direction of designing better laws such as making pre-legislative scrutiny of Bills mandatory through public feedback and identifying laws that need to be repealed but there is little discussion yet regarding the need for post-legislative review of laws.

What are the benefits of ex-post law reviews?

- To discover whether a law is working out in practice as it was intended

- To assess whether the objectives and the anticipated effects of a piece of legislation have actually taken place on the ground

- If not, to understand the reason and address it quickly and cost-effectively

- It also helps to identify any unintended effects that may have arisen from the legislation

- A key benefit would be the systematic collection of data that would be a pre-requisite of any evaluation of this kind.

Therefore, regular post-legislative evaluations would translate into better laws.

A crying need in India

For instance, let us consider Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act

- India enacted the NDPS Act in 1985 to tackle the growing drug menace in the country.

- When the concerned ministry (MoSJE) was questioned recently on whether there has been a reduction in substance abuse related cases, the minister answered that there was “no authentic data” available with the ministry.

- This is a symptom of the malaise that has plagued India’s law enforcement.

- The NDPS Act was amended thrice—in 1989, 2001 and 2014. Each time, the initiative was taken by activists and lawyers. Their concerns were mostly based on anecdotal evidence and independent studies done by researchers and scholars.

- Furthermore, the legislators themselves were hampered in their understanding due to the lack of information about the effectiveness of the law.

- They tended to rely on harsh punishments to deter drug users and traffickers but produced no evidence to make their case. They also never questioned the government on what evidence the Act was being amended multiple times.

Another example is the Right to Information Act

- RTI Act came into force in October 2005. Since its enactment, the government has made multiple attempts to curtail some of the powers of the Act on various grounds such as promoting efficiency and effectiveness

- In 2006 and 2009, the government tried to remove ‘file notings’ from the purview of the Act.

- Activists have staunchly resisted such attempts. However, the fact remains that there is no objective scrutiny of the effectiveness of the Act; so, both sides have depended on anecdotal tales to bolster their arguments.

Lessons from other countries

In the 1990s, many European countries as well as the US, Australia and Canada developed “better regulation” policies, which included ex-ante and ex-post evaluation of legislation.

- The UK requires its laws to be reviewed within three to five years of enactment. These reviews are conducted by existing Departmental Select Committees on the basis of a memoranda provided by a government department.

All Acts passed since 2005 are reviewed with a few exceptions such as budgets, very technical acts and trivial acts.

- In Germany, ex-post evaluation is systematic and based on a standardized methodology set out in guidelines for public administrators.

- France requires mandatory periodic evaluation of legislation, which is enshrined within the law itself.

- In the US, each standing committee, except Committee on Appropriation, is required to review and study, on a continuing basis, the application, administration, execution, and effectiveness of the laws dealing with the subject matter over which the committee has jurisdiction.

- In Australia, most laws have to be reviewed within two years and they expire after 10 years.

- In Canada, a most laws have review and sunset clauses.

The way ahead:

- There is an urgent need to develop a “better regulation” policy tool for India on the similar lines of above countries.

- The present government’s promise of delivering “good governance” could get a boost if it adopted post-legislative evaluation as a policy tool.

- The Law Commission or an expert committee could first decide, with inputs from government and non-government stakeholders, the scope of post-legislative scrutiny by defining its boundaries, the types of legislation that require scrutiny, benchmarks of a successful legislation, the procedure for scrutiny, the body that should undertake the scrutiny and the time-period of the scrutiny.

- India could then incorporate within its legislation, a provision for systematic review of the law.

Connecting the dots:

- Apart from ex-ante evaluation of legislation, India needs a strong ex-post legislative scrutiny tool. Do you agree? Support your view with some examples.

- Developing a “better regulation” policy tool for India could lead to good governance. Substantiate.

ENVIRONMENT

TOPIC: General Studies 2

- Conservation, environmental pollution and degradation, environmental impact assessment

A strained relationship: ULB’s & Water

- In years to come, water, is possibly to pose greatest challenge on account of its increased demand with population rise, economic development, and shrinking supplies due to over exploitation and pollution.

- In India, with development, the demand of water is increasing both in urban and rural areas. This may create increased tension and dispute between these areas for sharing and command of water resources.

- The emerging scarcity of water has also raised a host of issues related to sustainability of present kind of economic development, sustainable water supply, equity and social justice, water financing, pricing, governance and management of water.

Grief-struck ULBs:

There is given zero autonomy to the ULBs to set prices to cover costs (State government decides). Politicians are reluctant to charge even when consumers are willing to pay, more especially if it leads to better delivery of good quality water.

Journey of water needs to be fuelled by heavy investment—

- Collection from a natural source

- Treatment it to make it potable

- Putting in place a distribution network of pipes for delivery to the users

- Huge investments in sewerage infrastructure and sewage treatment plants so that the sewers can carry the wastewater (estimated to be 80 per cent of the water that is consumed) to these plants to ensure that no untreated sewage is discharged back into natural water bodies

Recommendations unfulfilled:

- Poor should be subsidized with putting in place volumetric pricing (also recommended by the 2012 Water Policy & the Vaidyanathan Committee in 1992) with a low price for the first slab which covers what is regarded as a minimum need

- Water rates should cover O&M costs in the first instance, with capital charges (interest and depreciation) to be covered over a period of five years (Vaidyanathan Committee in 1992)

- Progressive pricing: Those consuming more should pay a progressively higher price per litre for the water they consume

A statutory regulatory authority

Water pricing should be shifted away from the shadows of politics and be assigned to a statutory regulatory authority

Task:

- Determining water tariff for cost recovery allowing for reasonable costs

- Hear all stakeholders and formulate a standard mechanism for pricing

- No alteration be allowed from government

- Government should be allowed to introduce a subsidy which can be paid directly to the targeted consumers after making necessary provision in the budget—making the pricing of water transparent, and help begin the transition to a system of public debate on the importance of cost recovery and scrutiny of cost elements.

O&M Cost Recovery

Case Study of Singapore for understanding the dynamics—

- Singapore started pricing water to cover O&M costs in the second half of the 1960s. Singapore has made the maximum progress in addressing their enormous water challenge through:

- Full cost recovery (including capital cost)

- Marginal cost pricing

- Investing in innovations to reclaim water for reuse (NEWater)

- Investing in Desalination

- They also introduced a progressive water conservation tax in 1991

In India—

- In India, the situation varies across and within states—Maharashtra (64 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (including Telangana— 52 per cent) and Gujarat (49 per cent) come across much better than other states in O&M cost recovery.

- In terms of cities:

- Mumbai is the only big city reporting 100 per cent cost recovery (lowest tariffs as its water cost and energy cost is relatively low)

- Bengaluru is next with cost recovery of 92 per cent

- Worst: Delhi, Indore and Bhopal

The Curious Case of Non-revenue Water (NRW)

- NRW is the water which is produced but lost, and not paid for

- Working group on urban and industrial water supply and sanitation for the 12th Plan estimated NRW in India at 40-50 per cent

Loss:

- Leakages in pipes

- Theft

- Incomplete billing

- Metering inaccuracies

Solution:

- Data Collection: the methodology for NRW calculation needs to be streamlined

- Cities should be made to submit a water balance sheet (Nagpur)

Towards a better governance— ULB’s need to

- Reduce costs through modernisation and technology

- Recover costs through user charges, while financing whatever subsidies are intended for the poor through cross-subsidisation

- Make it mandatory for the State to come up a water Balance Sheet and collect bills

- Formulate a working revenue model to initiate private financing to supplement public funds to lay out the infrastructure with the consent of all the stakeholders

- Promote decentralized initiatives in waste water treatment by providing incentives and a supporting policy environment and through capacity building of implementing institutions and stake holders

- Support implementation of pilots and projects which demonstrate how communities and local administration can partner to implement the interventions in ways that make the facilities more durable and sustainable in the long run

- Intensive capacity building programs, appropriate IEC materials, technical manuals and documentation, and sharing of best practices amongst facilitators are required urgently

Connecting the Dots:

- The prevailing ‘adhocism’ in protecting, enhancing and conserving water needs to be done away with. Discuss the statement

Refer:

The importance of Water Management

MUST READ

BREXIT Articles in National Dailies

Why Brexit is a cautionary tale for us all

Brexit is a revolt of a significant section of England against itself

Brexit’s impact on India: when elephants fight, the grass suffers

Brexit casts dark shadow on world’s great move to openness

Related Articles:

EU referendum: the big questions for Britain

MIND MAPS

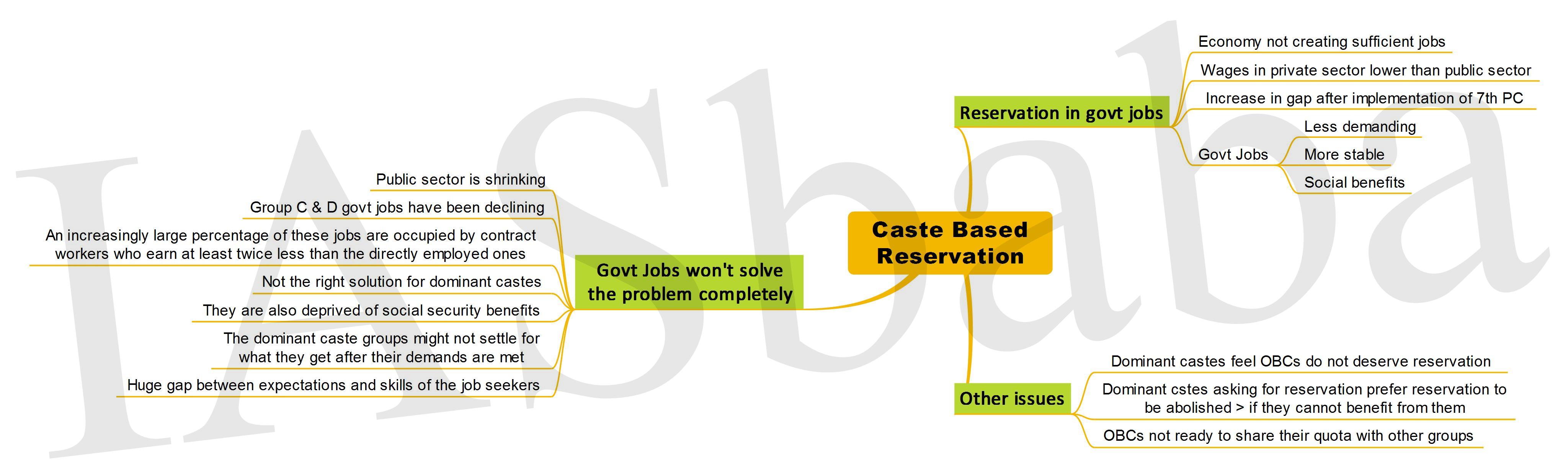

1. Caste Based Reservation