IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs June 2017, IASbaba's Daily News Analysis, National, UPSC

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 10th June 2017

Archives

NATIONAL

TOPIC:

General Studies 3:

- Issues related to direct and indirect farm subsidies and minimum support prices

- Inclusive growth and issues arising from it.

General Studies 2:

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

- Welfare schemes for vulnerable sections of the population by the Centre and States and the performance of these schemes; mechanisms, laws, institutions and bodies constituted for the protection and betterment of these vulnerable sections

Understanding the agitating farmers

In news: Farmers in two of the largest states of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra have resorted to agitation. The protests have come soon after the Uttar Pradesh government waived farm loans earlier this year, setting off similar demands in other States. Farmers from Kerala in April, 2017 staged protests at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar carrying skulls of fellow farmers who have committed suicides.

Farmers’ demands:

- Full waiver of farm loans.

- Hikes in the minimum support price for agricultural produce.

- Writing off of pending electricity bills.

Government’s response:

Maharashtra government promised to waive farm loans of small and marginal farmers worth about Rs. 30,000 crore and set up a State commission to look into the matter of raising the MSP for crops. The Chief Minister also promised that buying agricultural produce below their MSP would soon be made a criminal offence.

Issues:

- Indian farmers faced two consecutive years of drought in 2014-15 and 2015-16. Such an occurrence — two droughts in a row — only happened five times since 1870, and on three occasions in independent India: The mid-sixties, the mid-eighties and now. Despite this rare farmer tragedy, we did not observe any farmer riots during the recent drought years.

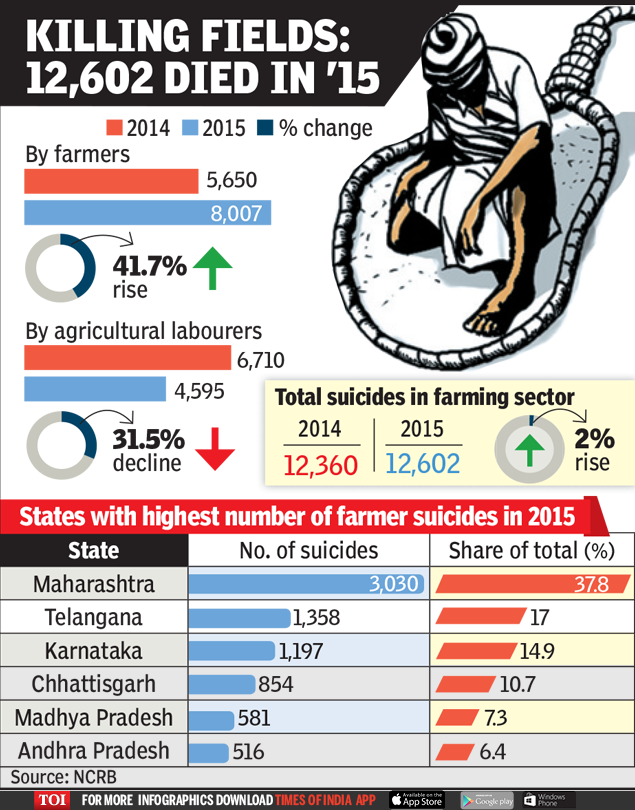

- More than 5,500 farmer suicides were recorded in 2014 and the figure rose at least 40% in 2015, with Maharashtra contributing the most, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.In Maharashtra, which witnessed the highest number of farmer suicides between 2014 and 2015. Between 2014 and 2015, the state saw an 18 per cent jump — from 2,568 to 3,030.

- The National Crime Records Bureau attributed the reasons to crop failure, failure to sell produce, inability to repay loans, and other non-agriculture factors such as poverty and property disputes.

Pic credits: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/farmer-suicides-up-42-between-2014-2015/articleshow/56363591.cms

Why are farmers agitating?

- Socio-economic reason:

The socio-economic explanation is that nobody wants to be a farmer anymore. Because it is unremunerative, and relatively hard physical work. The children of farmers aspire for a well-paying urban job. But the economy is not producing enough jobs to accommodate the migrants from farmer families. This leads to frustration, despair, unrest. Hence, the riots.

- The rural-urban wage gap is wide at 45%, almost four times that of China. The share of farming in GDP is under 14%, although more than half of India’s 1.25 billion people still depend on it.

- Demonetisation: The Centre’s decision to demonetise high-value currency notes in November last year came as a severe jolt to farmers as cash is the primary mode of transaction in agriculture sector.

- Pricing of agricultural produce:

- Steep fall in the prices of agricultural goods: The price slump, significantly, has come against the backdrop of a good monsoon that led to a bumper crop. The production of tur dal, for instance, increased five-fold from last year to over 20 lakh tonnes in 2016-17.

- Irrespective of price fluctuations, MSPs are supposed to enable farmers to sell their produce at remunerative prices. But procurement of crops at MSP by the government has traditionally been low for most crops, except a few staples such as rice and wheat. This has forced distressed farmers to sell their produce at much lower prices, adding to their debt burden.

- In Madhya Pradesh, this year was the second year of a bumper onion crop with no buyers. Farmers were forced to sell produce at for Rs 2 to 3 per kg as the state government delayed announcing procurement price of Rs 8 per kg. 33% of onion procured by the government rotted in absence of adequate storage facility

- Our farm subsidy policy encourages the production of only low-value staples, such as rice and wheat, and the output of fruits and vegetables — that more Indians are eating and farmers producing — is not covered by the government’s minimum support price. Much of the farm distress sweeping India now stemmed from a glut of potatoes, onion and tomatoes.

- Agriculture still at mercy of monsoon rain:

- For far too long, farming has been at the mercy of nature, especially the June-September monsoon rain.

- Agriculture in India is facing a tough time because of its dependence on the monsoon. Over 50% of the crop area does not have any irrigation facility and almost three-fourth of the annual rainfall is concentrated in four months a year, between June and September. A deficit monsoon for two consecutive years in 2014 and 2015 and unseasonal showers ahead of the winter harvest in 2015 have hit the farmers hard. Entire south India is bearing the brunt and Tamil Nadu is facing the worst drought in 140 years.

- Poor productivity:

- The use of technology is patchy, and only one-tenth of every rupee the government spends on rural areas goes to improving productivity — which is why farmers in India grow 46% less rice an acre than their Chinese counterparts.

- Agricultural market- Yet not reformed:

- The monopoly of traders over local agricultural markets is perpetuated by law, which bars farmers from selling directly to consumers. This kills any chance of farmers getting a fair price, lining the pockets of commission agents instead.

- Politicisation:

- The cardinal malaise lies in successive governments treating agriculture as a source of votes and not an engine of growth

Why farm loan waivers is not a solution?

Farm loan waivers are only a “temporary necessity” to address the agricultural crisis in the country and not a permanent solution to the problem, according to MS Swaminathan, agriculture scientist and the architect of India’s Green Revolution in the 1960s.

With poor extent of indebtedness and reported increase in suicides among farmers in distress, loan waivers appear as the easy solution to the problems of the farming sector. But it comes at a cost.

Issues related to loan waiver –

- Farm loan waivers disrupt “credit discipline” among borrowers as they expect future loans to be waived as well.

- It does increase the problem of moral hazard by penalising sincere and law abiding farmers.

- It gives rise to a tendency to default if the loan waivers are not a one-time solution but keep appearing every decade.

- It certainly leads to a deterioration in the performance of banks but also has an impact on credit off-take and repayments. It was the same approach of writing off loans of big corporate defaulters which has led to a situation of unprecedented NPAs in the banking system.

- But it also penalizes the small and marginal farmers who are more dependent on non-institutional sources of loan such as the local moneylender. The interest on these loans is higher but these are excluded from any loan waiver scheme.

Way ahead:

- The old, labour-intensive methods must give way to technology for efficiency and higher yield

- Pricing and subsidy mechanism must be overhauled.

- The focus should be more on making the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana a success rather than demanding farm loans waivers from banks.

- The government should look at diversifying the cropping pattern and developing new technology to fight drought. Bringing green revolution to eastern India(BGREI) must be implemented in true spirit.

- The Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, the new crop damage insurance scheme approved by the Union cabinet in January 2016, is also a vast improvement on the old crop insurance model in vogue since 1970s. The new scheme which has the lowest premium so far has proposed use of remote sensing, smart phones and drones for quick estimation of crop loss and speedy claim process. The focus should be more on making this a success.

- Conserving water, improving the irrigation facilities, and developing agriculture markets and competition can be the building blocks for growth in agriculture and mitigating farmers’ woes. State governments are barking up the wrong tree by resorting to loan waivers.

- The only long-term solution is to gradually align crop production with genuine price signals, while moving ahead with reforms to de-risk agriculture, especially by increasing the crop insurance cover. Expediting steps to reform the Agricultural Produce Market Committee system and introduce the model contract farming law would go a long way to free farmers from MSP-driven crop planning

Conclusion:

To be sure, India is reforming parts of its economy. But not farming. If farmers are to escape poverty, farming needs to become more like manufacturing: Teched up operations, free as far as possible from imponderables, churning out quality produce that fetch the right price. It is imperative that policymakers and analysts understand the causes behind the riots in order to best insure society, and farmers, from economic doom.

In the past, a single season of dry spell was enough to send the economy into recession. Now failed monsoons trigger localised distress. That’s an improvement. Still, far too many farm households remain too poor. And unless the rural economy is unshackled from a time and policy warp, our dream of double-digit economic growth will remain just that: A dream.

Connecting the dots:

- Recent riots by farmers from states of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh shows how despite continuous efforts by the government the state of agriculture remains grim. Discuss what are the reasons behind rioting farmers and what should be done to improve livelihood of farmers and Indian agriculture.

NATIONAL

TOPIC: General Studies 2

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

A calibrated approach to reforms

- It was a common thing to make bureaucracy responsible for inexplicable delays in policy formulation and implementation.

- The bureaucracy was seen as the biggest stumbling block for a policy-driven progress.

- However, in the hindsight, it has been now validated that India’s calibrated, less hurried approach to opening up the economy in certain sectors was against the convention of the time. But the reality is now different.

- Though it is always tempting to suggest that policy makers should hit the reforms accelerator, the complex present is the truth.

Making the right policies

- There is no merit in following the herd in thinking and implementing the popular policy choices. Prudent policy making steers clear of such approaches.

- Rather, there is a need to evaluate the policy choices on the merits of the argument. Though some might think it as a delaying tactic, but given that policymaking is both an art and a science, the policy maker should take all the arguments and choices available to make an informed decision.

- As economist Dani Rodrik argued “When knowledge is limited, the rule for policy makers should be, first, do no harm”. This can be explained as

- When India approached IMF in 1991 for loans to tide over its balance of payments crisis, there were conditionalities wherein IMF called for liberalisation of India’s current and capital accounts.

- Yet, India moved towards current account convertibility, it wasn’t fast on capital account convertibility which was conventional thing to do.

- However, when India was recovering from her 1991 financial crisis, another crisis was in the making in the East Asian Countries which had already embraced full capital account convertibility.

- There was a heavy capital inflow in these countries which when coupled with fixed exchange rate regimes resulted in asset bubble burst in 1997.

- Thus, post the crisis, there was new policy understanding about the difference between the theory and practice of capital account liberalisation and how free movement of short-term capital flows had destabilising effect on individual economies.

- Contrastingly, India’s approach of gradual lifting of capital controls was considered sustainable.

Sub prime crisis

- During the global economic recession of 2008, India was amongst the less affected countries.

- This was because till them RBI had not allowed Indian banks to invest in synthetic structured products like MBS, CDOs, and CDS.

- The irony is in the fact that these products were rated AAA despite having sub-prime American housing loans.

- A conservative approach towards such instruments saved India from the direct contagion risk of the great recession whereas US and European banks had invested heavily in subprime tranches and hence were largely affected.

- The lesson learnt was- earlier, accepted wisdom that free capital flows across borders would usher in higher investments and work as tonic for sick economies proved not completely true.

- In 2012, IMF came around to the view that robust institution building should precede capital liberalisation. Also, that free capital flows at times, might do more harm than good.

Trade liberalisation

- The theories mending the trade liberalisation policies has changed over the time period.

- Earlier the convention was to protect infant industry by giving state support through high import tariffs or domestic subsidies until the industries have matured and attained economies of scale.

- During WWII, US had one of the highest import tariffs in the world.

- Now, the conventional wisdom has changed over time. With the era of globalisation and incoming of WTO agreement, trade facilitation has changed.

- India has two examples of diametrically opposite views made by the policymakers which resulted in two different results which hold a lot of value.

- When India signed the Information Technology Agreement (ITA-I) in 1997 under WTO’s Singapore Ministerial Conference it removed tariff protection for IT hardware products covered in the agreement.

- Thus, electronic hardware imports became cheap which led to huge influx of Japanese, Korean and Chinese manufactured IT hardware.

- This negatively impacted Indian nascent electronics manufacturing as other countries had built their capabilities previously whereas in India, the infant IT manufacturing industry was barely born.

- The effect today is such that Indian presence in this industry is hardly felt.

- On the other hand

- The auto and auto-ancillary sector in India was protected through high import duties and other conditions in terms of mandatory localisation provisions and investment restrictions

- This led to healthy growth of auto sector in India. Today, India is a hub of world class auto and auto parts sector.

- This led to slowly withdrawal of most restrictions except high duties on fully assembled vehicles.

Conclusion

There was a time when India was considered as a slow liberaliser and high import tariff country. But om infact it was this organised policy making and long term vision which has helped India in most sectors.

Today the world is once again turning to high import duties to protect their domestic jobs and also restrict China from spreading its tanctacles of becoming manufacturing hub in Asia.

India is in a good position in critical areas and sensitive sectors. Though it is not that policy reforms should continue at slow rate only, but to consider diverse developmental strategies possible while making a policy for a complex society.

Connecting the dots:

- Though it is considered that fast paced reforms are key to faster economic growth, the reality has been different. Do you agree? discuss in detail how reforms in policies should be shaped.

MUST READ

Fault lines in the fields

The arc to Tokyo

Proper protocol

The Kerala model

UK’s election of delusions

Time for reflection, fellow doctors

Uncertainty in Britain

Three crucial stumbling blocks in farming