IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Analysis, IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs Aug 2017, IASbaba's Daily News Analysis, UPSC

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 19th Aug 2017

Archives

ECONOMICS

TOPIC:

General Studies 2

- Welfare schemes for vulnerable sections.

- Issues relating to poverty and hunger.

General Studies 3

- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment.

- Inclusive growth and issues arising from it.

Migration and Gender

Background:

Since the 1970s, the nature of urbanisation across the globe, including India, has been increasingly shaped by corporate capital under the neo-liberal policies of the state. Cities are treated as consumer products, with massive private investment in real estate and housing, malls, expressways, flyovers, waterfronts, sports and entertainment facilities, and policing and surveillance to promote corporate urban development. Urban amenities and services are privatised, and labour reforms are undertaken to benefit corporate capital.

The urban poor, slum dwellers, and migrants (both male and female) are dispossessed as a result of urban restructuring and gentrification. These exclusionary processes began in 1990 and are acute in Indian cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Bengaluru, and Hyderabad.

Government Policy:

The central government started the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission in 2005—which was renamed as the Smart Cities Mission in 2015—with the primary aim of accelerating neo-liberal urbanisation policies to promote economic growth.

This has also led to various urban protests and movements in different parts of India related to such issues as the restructuring of urban space, demolition of slums, displacement, and the relocation and privatisation of urban amenities.

Right to city:

Migration raises the central issue of the right to the city: the right of everyone, including migrants (men and women), minorities, and the marginalised to access the benefits that a city offers.

The right to the city perspective ultimately seeks to achieve urban transformation that is just and equitable in contrast to urbanisation based on neo-liberal policies, which promotes exclusion, deprivation, and discrimination.

Right to the city is also expected to unite disparate categories of deprived people under the common vision of building our future by building cities.

The right to the city is not an exclusive individual right. Rather, it is a collective right, which aims to unify different exploited classes to build an alternative city that eradicates poverty and inequality and heals the wounds of environmental degradation

While it is true that cities have evolved through migration, cityward migration, and interstate migration in particular, has been sensitive issue in India. India is a federal country and states are organised along linguistic lines. Linguistic differences are essentially cultural differences, which are pronounced in the event of migration.

In India exclusion and discrimination against migrants takes place through political and administrative processes, market mechanisms, and socio-economic processes.

Challenges faced by migrants:

- Though the Constitution guarantees freedom of movement and freedom to settle within India as a fundamental right of all citizens (Article 19), migrants face several barriers in their ability to access civic amenities, housing, and employment.

- They also encounter restrictions on their political and cultural rights because of linguistic and cultural differences. Discrimination against migrants is articulated in various parts of India under the “sons of the soil” political ideology, which simultaneously justifies the natives’ lay to claim on local jobs while blaming migrants for snatching them away.

- Migrants are also vulnerable to discrimination and exploitation as many of them are poor, illiterate, and live in slums and hazardous locations that are prone to disasters and natural calamities.

- Urbanisation, as a vehicle of capital accumulation, has been associated with an increased concentration of wealth in big cities and urban centres; rural–urban gaps in income, wages, and employment opportunities have also widened. Exclusion and deprivation are ubiquitous in cities as every 50 urban dweller lives in a slum and about 90% work in the socially unprotected informal sector with very low wages and salaries.

- The limited access that migrants, both men and women, have to health services is a very serious issue. Public health services are generally lacking and private health services are too expensive. In most cases, migrants are neither able to reap the benefits of health insurance schemes nor are they provided with health insurance by their employers. They also face greater risk of contracting HIV/AIDs

- Lack of proofs of identity and residence in the city is the biggest barrier to inclusion of migrants.

- Due to a lack of proof of residence, many are not included in the voter list and cannot exert their right to vote.

- Lack of residential proof leads to the inability to open a bank account, get a ration card, or a driving licence. It is noteworthy that residential proof depends upon a migrant’s ability to own a house in his or her name or in the name of a family member, or rent a house under a leave and licence agreement. The recent Unique Identification project also insists on residential proof. Women generally lack access to property and housing rights, and the condition is worse for them when they migrate with their husbands or other relatives.

- The denial of political rights (of voting) to migrants, both men and women, is crucially linked to being denied the right to housing in the city.

- Due to a lack of proper housing, many migrants live in informal settlements and are unable to acquire residential proof. Also, as most of them work in the informal sector, they cannot get any proof of identity from their employers, unlike their counterparts who work in the formal sector.

- Lack of housing is a serious problem for migrants in Indian cities.

- Children of migrants are denied their right to education as seeking admission to schools is cumbersome, and language barriers are difficult to overcome. Migrants’ languages are generally different from the local language, and this adds to their disadvantages.

- In most cities, segregation along caste and community lines is still very prominently visible.

Migration and Gender

Women’s Migration to Cities:

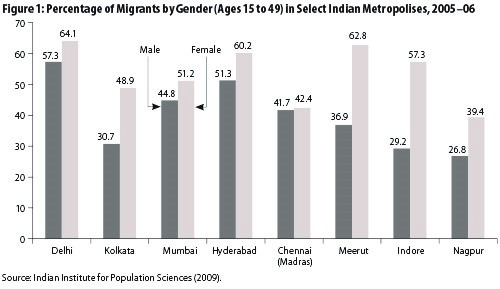

In cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Bengaluru and Pune, there have been increases in female migration. In fact, the increase in female migration is evident across all classes in urban centres. Women constituted the majority of migrants in most cities between 2005 and 2006. As most of these women do not work, this shapes their relationship with the city, especially with regard to access and use of the city space and resources. On the other hand, their contributions as homemakers and family-care providers are enormous, but seem to be structured through the continuity of patriarchal traditions transmitted from rural to urban areas.

Pic Credit: http://www.epw.in/system/files/Per_RB_Bhagat_Fig1.jpg

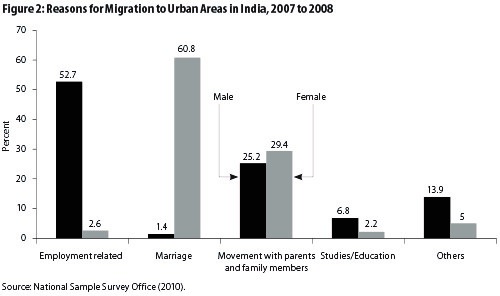

National statistics on migration show why men and women migrate:

Pic credit: http://www.epw.in/system/files/Per_RB_Bhagat_Fig2.jpg

There is a huge disparity between men and women migrants in urban areas. The available data indicate that the participation of women migrants in the workforce has declined; about two-fifths of those who were either self-employed or casual workers prior to migration lost their work after moving to urban areas as per the 64th round of the National Service Scheme (NSS) survey conducted from 2007 to 2008. This shows some amount of de-feminization of the migrant workforce.

Women in the city suffer the consequences of being migrants and women, in addition to inherent sociocultural prejudices and economic deprivations. Migration adds to the existing baggage of inequality and discrimination. Migrant women not only face wage discrimination, but also sexual violence and various types of exclusion, such as restricted access to the public distribution system for food, to shelter and medical facilities, and may even have limited voting rights. Many women migrant construction workers are denied access to crèches, drinking water, sanitation, and toilets.

Urbanization is often associated with the greater independence of women and the erosion of patriarchal power relations and values.

However, Indian cities have failed to achieve the goal of gender equality, as patriarchal norms continue to play an important role in the urban social structure—these norms have been transplanted to urban areas from rural areas through migration with few social reforms.

Issues related to women migrants:

- Government policies and programmes are silent on the issue of migration and on the need to protect the rights of migrants.

- Concerns related to gender and migration are not addressed, and the rights of women migrants do not find an equal place in city development plans.

- Access to economic, social and health benefits are denied because of hostile attitudes, discriminatory practices and even legal frameworks based on the “sons of the soil” ideology.

- As women migrants continue to suffer at the hands of patriarchal values and practices, discriminatory practices deny them the right to the city.

- Shortage of urban amenities and lack of access to housing increases their suffering, but they still contribute immensely to the city as domestic servants, unpaid household workers, construction workers, and other workers.

- A large proportion of women migrants live in slums, although this proportion varies from city to city. In some cases, women are affected more than men migrants in their access to housing, water and sanitation.

- Women migrants face various types of discrimination, barriers and exclusions.

- Patriarchal power relations continue to be embedded in religious, caste, place, and gender-based identities in cities, despite increased urbanization and mobility. The decision of whether women family members can work outside the home is often made by men.

- Working women have to take care of both household chores and workplace duties, have little control over their salaries and wages, and are dependent on men for their movement.

- Migration has taken women from the sphere of traditional gender relations in rural areas to a new patriarchal set-up embedded in the conjugal family system and the separation of the living space from the workplace.

- Studies show that women migrant workers are more vulnerable to violence and exploitation in the workplace than their male and non-migrant counterpart. Gendered power relations also influence women’s private lives as well as their access to and use of public spaces. Women’s safety and security are a matter of great concern in cities, and these issues take an acute form with respect to migrant women.

- Recently, there was a public outcry regarding the Nirbhaya rape case. Nirbhaya was a migrant woman who was waiting for public transport at a bus stop in Delhi for hours. Women’s access to safe public transport when they travel alone or walk around poses powerful restrictions on their mobility and right to the city.

- A lack of water supply in the residential premises also forces women to spend more time on water collection. The availability of schools, hospitals, and crèches in the neighbourhood, or within walking distance, matters to women in particular.

- Urban infrastructure and services are usually not gender-neutral, as men and women do not have equal access. In general, Indian cities do not show gender sensitivity in urban planning and policies. There is an appalling shortage of basic amenities in Indian cities such as access to water, sanitation, cooking fuel, and a supply of electricity. As many women have to take care of household and workplace duties, the lack of such basic services represents a failure of the state and reinforces the patriarchal structure of society and denies them their right to the city.

Conclusion:

The issues mentioned above should be a central concern for city planning and development agendas, and efforts should be made to integrate migrants and women politically, economically, socially, culturally and spatially. This requires an enormous change of attitude in those who appropriate and dominate cities towards the processes of migration and urbanization. A historical understanding of the processes of migration and urbanization, and migrants’ roles in building cities, must be highlighted.

The democratization of city governance, and the political inclusion of men and women migrants in decision-making processes, are important steps to ensuring the right to the city for all, for promoting alternative urbanization, and building cities based on the principles of freedom, human development and gender equality.

A gender perspective on the right to the city envisions the safe movement of all women (including migrant women) within a city, their safety and security in both public and private places, access to the social and economic resources of the city without any prejudice, and their participation in building the city. This requires a paradigm shift in the ideology of a city from being a source of gross domestic product and economic growth to a space that is environmentally sustainable, woman-friendly and inclusive.

In this light, the constitutional provisions under the 74th amendment to reserve one-third of seats for women in urban local bodies should be implemented in letter, spirit and practice. Women should be given responsibility in planning and decision-making processes in municipal administration bodies.

MUST READ

Disease that won’t go away

Cause for caution not gloom

Getting charged

A healthy partnership

Unresolved issues of corporate governance

Justice for Hadiya

Sustainable farming