Governance

Context:

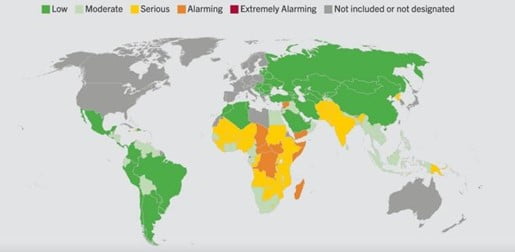

- Globally, food and nutrition security continue to be undermined by the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, spiralling food inflation, conflict, and inequality.

- Today, around 828 million people worldwide do not have enough to eat and over 50 million people are facing severe hunger.

- The Hunger Hotspots Outlook (2022-23) — a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Food Programme (WFP) — forebodes escalating hunger, as over 205 million people across 45 countries will need emergency food assistance to survive.

- This year’s World Food Day is a reminder to ‘Leave No One Behind’ — and is an opportunity, perhaps the most urgent one in recent history, for nations to strengthen food security nets, provide access to essential nutrition for millions and promote livelihood for vulnerable communities.

Challenges to Food Security:

- Global warming: More than 1,000 global and regional studies predict that a temperature rise of 1 to 2 degrees Celsius will translate into loss in yield of several crop varieties in tropical and temperate regions. An increase of 3 to 4 degrees will have very severe consequences for global food security and supply

- Higher temperatures, water scarcity, droughts, floods, extreme weather events and greater CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere will drastically affect staple crops around the world. It will also impact fishing and livestock farming.

- Indian agriculture is vulnerable to climate change because 65% of India’s cropped area is dependent on the monsoons.

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that a 0.5°C rise in winter temperature is likely to reduce wheat yield by 0.45 tonnes per hectare in India.

- The impact of climate change on water availability – 54 per cent of India faces high to extremely high, water stress.

- Groundwater levels are going down alarmingly in over 50 per cent groundwater wells in the country. This this will directly impact food production. While upping wheat production by 25 per cent and rice by 65 per cent to meet the demand in 2050 may not seem difficult it could prove to be a herculean task unless global warming is contained.

Better production:

- During 2021-22, the country recorded $49.6 billion in total agriculture exports — a 20% increase from 2020-21.

- India’s agriculture sector primarily exports agriculture and allied products, marine products, plantations, and textile and allied products. Rice, sugar, and spices were some of the main exports.

- India is also a provider of humanitarian food aid, notably to Afghanistan, and to many other countries when the world faces food supply shortages and disruptions, such as during the current crisis in Ukraine.

- By 2030, India’s population is expected to rise to 1.5 billion. Agri-food systems will need to provide for and sustainably support an increasing population. In the current times, there is an increased recognition to move away from conventional input-intensive agriculture towards more inclusive, effective, and sustainable agri-food systems that would facilitate better production.

- Given climate shocks and extreme weather phenomena, it is important to place a greater focus on climate adaptation and resilience building.

Better nutrition:

- Food safety nets and inclusion are linked with public procurement and buffer stock policy.

- This was visible during the global food crisis of 2008-12 and more recently during the COVID-19 pandemic fallout, whereby vulnerable and marginalised families in India continued to be buffered by the TPDS which became a lifeline with a robust stock of food grains.

- For instance, the PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) scheme introduced in 2020 provided relief to 800 million beneficiaries covered under the NFSA from COVID-19-induced economic hardships.

- An International Monetary Fund paper titled ‘Pandemic, Poverty, and Inequality: Evidence from India’ asserted that ‘extreme poverty was maintained below 1% in 2020 due to PMGKAY.

Better environment through Millets:

- Nutrition and agricultural production are not only impacted by climate change but also linked to environmental sustainability.

- The degradation of soil by the excessive use of chemicals, non-judicious water use, and declining nutritional value of food products needs urgent attention.

Millets — which fell out of fashion a few decades ago — have received renewed attention as crops that are good for nutrition, health, and the planet.

- Millets are climate-smart crops that are drought-resistant, growing in areas with low rain and infertile soil. They are hardier than other cereals, more resilient to changes in climate, and require less water to cultivate (as much as 70% less than rice), and less energy to process (around 40% less than wheat).

- Since they need fewer inputs, they are less extractive for the soil and can revive soil health. Additionally, their genetic diversity ensures that agrobiodiversity is preserved.

- India has led the global conversation on reviving millet production for better lives, nutrition, and the environment, including at the United Nations General Assembly, where it appealed to declare 2023 as the International Year of Millets.

- It is the world’s leading producer of millets, producing around 41% of total production in 2020.

- To enhance the area, production, and productivity of millets the national government is implementing a Sub-Mission on Nutri-Cereals (Millets) as part of the National Food Security Mission.

- State-level missions in Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh are an opportunity to guarantee food and nutrition security to millions while protecting the earth.

- Millet conservation and promotion contribute to addressing food security, improved nutrition, and sustainable agriculture, which aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals agenda.

- Millet production has been proven to enhance biodiversity and increase yields for smallholder farmers, including rural women.

- For example, the International Fund for Agricultural Development’s (IFAD’s) Tejaswini programme with the Government of Madhya Pradesh showed that growing millets meant a nearly 10 times increase in income from ₹1,800 per month in 2013-14 to ₹16,277 in 2020-21, with better food security because millet crops were not impacted by excessive rainfall.

- Women were key to villages adopting millets, as they were able to demonstrate that millets were easier to grow and led to better outcomes.

Better life:

- It is clear that the path to a better life resides in transforming food systems.

- This can be achieved by making them more resilient and sustainable with a focus on equity, including by incentivising the protection of the commons.

- Enhancing food and nutrition security and social protection networks, including by providing non-distortionary income support; promoting production and consumption of nutritious native foods such as millets.

- Investing in consumer sensitisation and in making the global and regional supply chain robust and responsive by strengthening transparency in the agricultural system through systems that promote labelling, traceability, etc.

- Increasing cooperation for leveraging solutions and innovations.

Government initiatives:

- Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana, which promotes organic farming;

- Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana, which focuses on more crops per drop for improved water use

- Soil Health Management which fosters Integrated Nutrient Management under the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture.

- Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY), the Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman Yojana (PM POSHAN Scheme), and take-home rations – for improving food access, especially for vulnerable populations

- National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013 anchors the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS), the PM POSHAN scheme (earlier known as the Mid-Day Meals scheme), and the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS).

Way forward

- Without food and nutrition security for all, there can be no peace and no prosperity. Only through collective and transformational action to strengthen agri-food systems, through better production, better nutrition, a better environment, and a better life, can we meet our promise to end hunger by 2030.

- India can lead the global discourse on food and nutrition security by showcasing home-grown solutions and best practices, and championing the principle of leaving no one behind — working continuously to make its food system more equitable, empowering, and inclusive.

- The upcoming G20 presidency for India provides an opportunity to bring food and nutrition security to the very centre of a resilient and equitable future and sharing its journey with the rest of the world.

Must Read: Food Security in India

Source: The Hindu